55-foot-long Triassic sea monster discovered in Nevada

The beast shows that ichthyosaurs grew big really fast.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A sea monster that lived during the early dinosaur age is so unexpectedly colossal, it reveals that its kind grew to gigantic sizes extremely quickly, evolutionarily speaking at least.

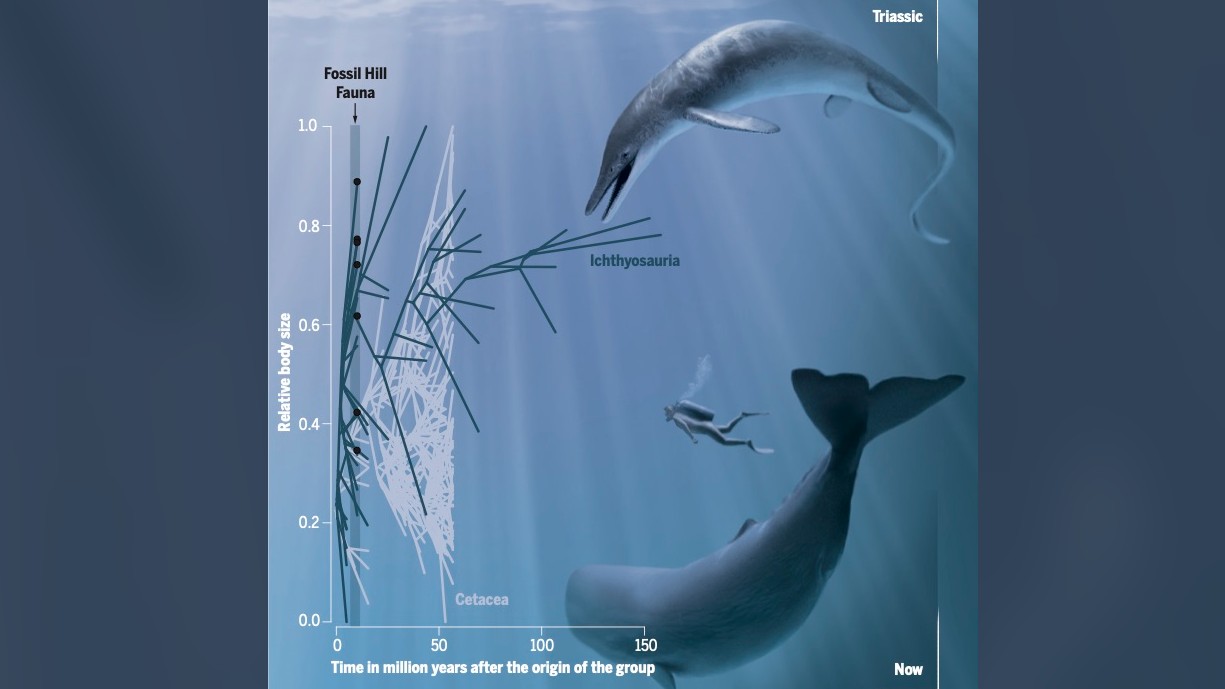

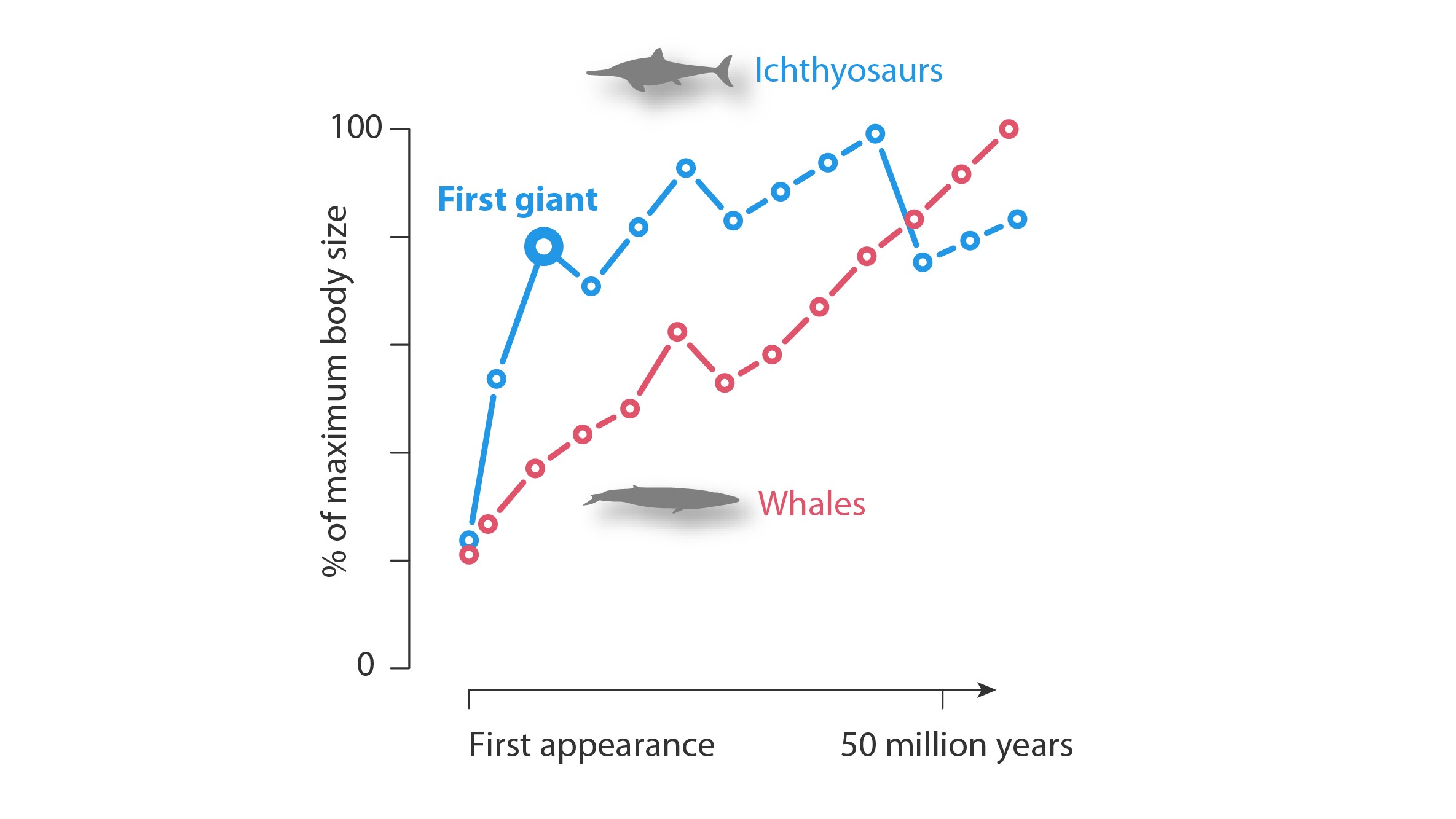

The discovery suggests that such ichthyosaurs — a group of fish-shaped marine reptiles that inhabited the dinosaur-era seas — grew to enormous sizes in a span of only 2.5 million years, the new study finds. To put that in context, it took whales about 90% of their 55 million-year history to reach the huge sizes that ichthyosaurs evolved to in the first 1% of their 150 million-year history, the researchers said.

"We have discovered that ichthyosaurs evolved gigantism much faster than whales, in a time where the world was recovering from devastating extinction [at the end of the Permian period]," study senior researcher Lars Schmitz, an associate professor of biology at Scripps College in Claremont, California, told Live Science in an email. "It is a nice glimmer of hope and a sign of the resilience of life — if environmental conditions are right, evolution can happen very fast, and life can bounce back."

Related: Image gallery: Ancient monsters of the sea

Researchers first noticed the ancient ichthyosaur's fossils in 1998, embedded in the rocks of the Augusta Mountains of northwestern Nevada. "Only a few vertebrae were sticking out of the rock, but it was clear the animal was large," Schmitz said. But it wasn't until 2015, with the help of a helicopter, that they were able to fully excavate the individual — whose surviving fossils include a skull, shoulder and flipper-like appendage — and airlift it to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, where it was prepared and analyzed.

The team named the new species Cymbospondylus youngorum, they reported online Thursday (Dec. 23) in the journal Science. This big-jawed marine reptile lived 247 million years ago during the Triassic period. Like other creatures from that time, it was weird. "Imagine a sea-dragon-like animal: streamlined body, quite long, with limbs modified to fins, and a long tail," Schmitz said. With a nearly 6.5-foot-long (2 meters) skull, this full-grown C. youngorum would have measured over 55 feet (17 m), or longer than a semitrailer, the researchers found.

When the 45-ton (41 metric tons) C. youngorum was alive, C. youngorum would have lived in the Panthalassic Ocean, a so-called superocean, off the west coast of North America, Schmitz said. Based on its size and tooth shape, C. youngorum likely ate smaller ichthyosaurs, fish and possibly squid, he added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

There are many huge beasts that lived during the dinosaur era, but C. youngorum stands out for several reasons. For instance, C. youngorum lived just 5 million years after "the Great Dying," a mass extinction event that occurred 252 million years ago at the end of the Permian period, which killed about 90% of the world's species. That makes the ichthyosaur's huge size all the more impressive, as it took about 9 million years for life on Earth to recover from that extinction, a 2012 study in the journal Nature Geoscience found.

However, there was a diversification boom of marine molluscs known as ammonoids within 1 million to 3 million years of the mass extinction, the 2012 study found. It appears that ichthyosaurs' venture into gigantism was, in part, due to chowing down on the early Triassic boom of ammonites, as well as jawless eel-like conodonts that filled the ecological void following the mass extinction, the researchers of the new study said. In contrast, whales got big by eating highly productive primary producers, such as plankton; but these were absent in dinosaur-age food webs, study co-author Eva Maria Griebeler, an evolutionary ecologist at the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz in Germany, said in a statement.

Despite the whales' and ichthyosaurs' different paths and timetables toward achieving gigantism, the groups have a few similarities. For instance, there is a connection between large size and raptorial hunting, just like sperm whales dive to hunt giant squid, as well as a connection between large size and tooth loss, just like the giant filter-feeding whales that are toothless, the researchers said.

"This new fossil impressively documents the fast-track evolution of gigantism in ichthyosaurs," Schmitz said. In contrast, whales "took a different route to gigantism, much more prolonged and not nearly as fast."

"Ichthyosaur history tells us ocean giants are not guaranteed features of marine ecosystems, which is a valuable lesson for all of us in the Anthropocene," paleontologists Lene Delsett and Nicholas Pyenson, who weren't involved with the research wrote in a related perspective published in the same issue of Science.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus