13 ways the Earth showed its wrath in 2020

As if a pandemic weren't enough.

In an already-dramatic year, our planet did not hold back from stirring the pot. 2020 brought a record Atlantic hurricane season, numerous life-threatening wildfires and several earthquakes severe enough to remind humanity of the strength of plate tectonics. Some of these disasters were part of the geological cycle; others were helped by human-caused climate change. Read on for a reminder of the ways Earth displayed its wrath in 2020.

The 2020 Caribbean earthquake

One of the largest earthquakes of the year, a 7.7 magnitude temblor, hit the Caribbean on Jan. 28, 2020. The quake hit 76 miles (122 kilometers) north-northwest of Lucea, Jamaica, and south of Cuba. No one died, but the shaking was felt as far away as Miami and parts of Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula, according to USA Today.

The region where the quake struck is at the plate boundary between the North American Plate and the Caribbean Plate. The period between late 2019 and early 2020 was an active time at the plate boundary, with Puerto Rico experiencing an earthquake series more severe than anything seen since 1918, Live Science previously reported.

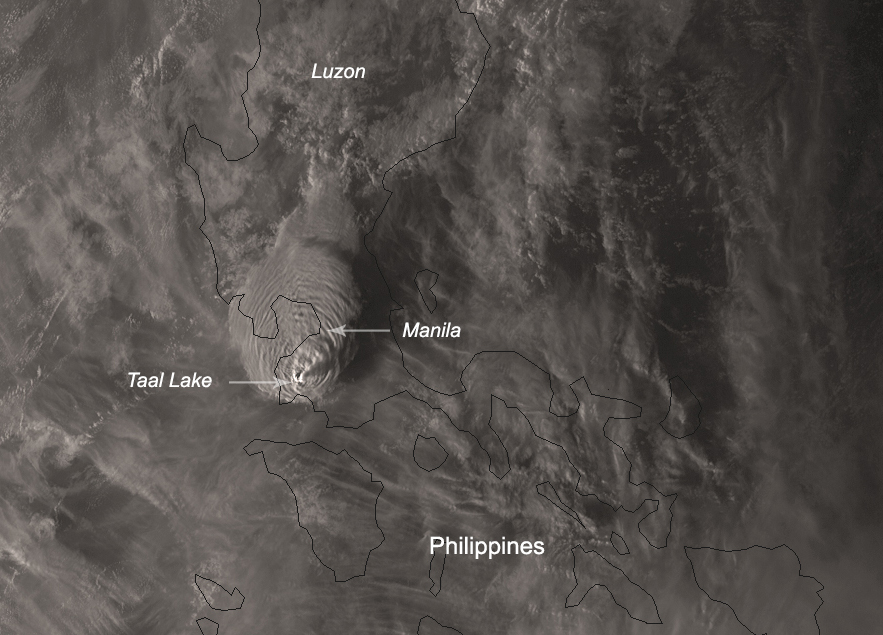

The Taal volcanic eruption

On Jan. 12, the Taal volcano on the Philippine island of Luzon belched to life in a big way, sending clouds of ash skyward. The eruption soon intensified, creating steam-and-ash plumes up to 9 miles (14 km) tall. It was the first time the volcano had erupted in 40 years. As clouds of ash drifted more than 100 miles (62 km) northward, residents living near the volcano had to evacuate. The Manila Bulletin reported that the eruption led to 39 deaths, most of which were the result of heart attacks or other medical events within evacuation centers, according to government officials.

Related: The deadliest earthquakes in history

The Elazığ earthquake

January's seismological unrest continued in Turkey on Jan. 24, when a 6.7 magnitude earthquake struck Elazığ province. Though this quake was smaller than the one that hit north of Jamaica, it was much more damaging: A reported 41 people died and more than 1,000 were injured. Many of the deaths were caused by collapsing buildings, which trapped dozens in the rubble as rescue crews struggled to reach them, CNN reported. According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the earthquake's epicenter was relatively shallow, at only 6.2 miles (10 km). Shallow earthquakes cause greater shaking at the surface, increasing the intensity and damage from a quake.

Australia megafires

At the beginning of 2020, the world watched in horror as wildfires swept through Australia, merging into megafires in Victoria and New South Wales. According to Eos, the 2019-2020 fire season in Australia burned more than 29.7 million acres (12 million hectares) and killed at least 33 people and more than a billion animals. Research published in the journal Earth's Future in November 2020 rounded up the climatic dominoes that led to this fiery cataclysm: long term drought, surface soil moisture, wind speed, relative humidity, heat waves, and the moisture content of the dead and living fuel for the fires. Land cover with native Eucalyptus and grazing land were particularly vulnerable.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Oaxaca earthquake

On June 23, a strong earthquake jolted Oaxaca, Mexico, causing buildings to sway as far away as Mexico City. The 7.4 magnitude quake was centered 5.6 miles (9 km) southeast of Santa María Xadani, on the Oaxacan coast, according to the USGS. Ten people died in buildings that collapsed as a result of the quake.

The quake took place in the subduction zone where the Cocos Plate is descending under the North American Plate. The movement of these two plates creates what are called reverse faults, which occur where Earth's crust is being compressed. It was one of these faults that slipped, causing the Oaxaca quake. This subduction zone also makes the southern Mexican coast seismically active in general. According to the USGS, the region has seen at least four quakes of magnitude 8 or above in the past century.

A jolt in Alaska

The most powerful earthquake of 2020 was a 7.8 magnitude temblor that struck off the coast of Alaska on July 22. The quake occurred on a thrust fault where one chunk of seafloor slid over another; this region off of Alaska is another subduction zone, where the Pacific Plate is sliding under the North American Plate.

Fortunately, the Alaska Peninsula is sparsely populated, and no one died in the quake. Though there was a tsunami warning issued, no wave materialized — a relief to evacuated locals.

August Complex Fire, California

Just as Australia experienced a dramatic fire season, North America saw its share of flames once summer rolled around in the Northern Hemisphere. California was particularly affected, with more than 4.1 million acres (1.65 million hectares) burned, 10,488 structures destroyed and 33 deaths, according to CalFire. Among the fires that tore through the landscape was the largest in California's recorded history, the August Complex Fire. This fire consumed more than 1 million acres (400,000 hectares) in Mendocino, Humboldt, Trinity, Tehama, Glenn, Lake and Colusa counties. It took three months to fully contain the fire, which started with lightning strikes on Aug. 16 and 17.

Cameron Peak Fire, Colorado

As California was reeling from the August Complex Fire and other blazes around the state, a wildfire in Colorado was also setting new records. The Cameron Peak Fire, which began Aug. 13, scorched 208,913 acres (84,544 hectares), making it the largest wildfire in Colorado history as well as the first wildfire in the state to burn more than 200,000 acres (80,000 hectares). The fire unseated the previous record, set only a month before, when the Pine Gulch Fire, near Grand Junction, blazed over 139,007 acres (56,254 hectares). The Pine Gulch Fire was subsequently knocked into third place by the East Troublesome Fire, which sprung up on Oct. 14. That means the top three fires in Colorado history all occurred in 2020. Their explosive potential was driven by drought, heat and ample fuel: The mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) has killed massive swathes of pine forest in the state, in part due to warmer temperatures driven by climate change.

A fatal quake in Turkey

At 2:51 p.m. local time on Oct. 30, a 7.0-magnitude earthquake rocked Turkey, killing 117 people and injuring more than 1,000. Two additional people died in Greece.

The epicenter of the quake was in the Aegean Sea, and it triggered a small tsunami that flooded streets in Izmir's Seferihisar district. At least one person drowned. Most of the deaths, however, were due to collapsing buildings in the Turkish town.

Turkey is situated in a seismically complex region, with interactions between Africa, the Eurasian Plate and the Anatolian microplate. There have been 29 magnitude 6 or greater quakes in the area in the past 100 years, according to the USGS.

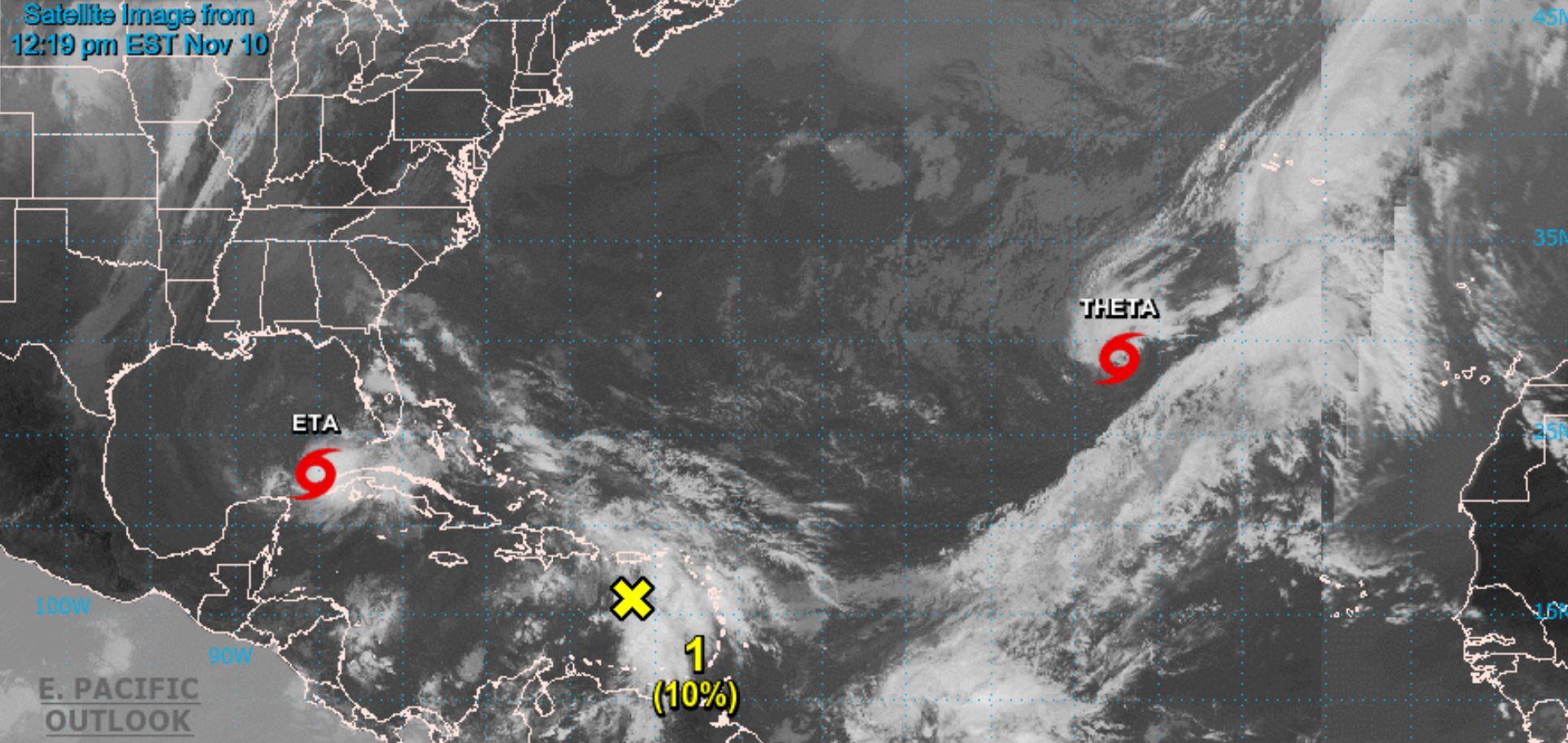

Hurricane Eta

The record-shattering 2020 hurricane season saw a whopping 30 named storms, 13 of which became hurricanes, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The season ran through all of the names prepared for this year, from Arthur to Wilfred, and rushed right through the Greek alphabet all the way to Iota. Of all these storms, the most deadly was Hurricane Eta, a Category 4 storm whose sustained winds peaked at 150 mph (240 km/h). Approximately 150 people in Central America lost their lives, many after being buried in mudslides in Guatemala. The storm also caused an estimated $7.2 billion worth of damage.

Eta was one of four Category 4 storms in 2020. The others were Hurricane Laura, Hurricane Teddy and Hurricane Delta.

Hurricane Iota

The 2020 hurricane season brought one storm that reached Category 5 strength: Hurricane Iota, whose sustained winds hit 160 mph (260 km/h). Iota formed on Nov. 13, making it the most recent hurricane to strengthen to a Category 5 storm. (Category 5 hurricanes have sustained winds over 157 mph, or 252 km/h.) The storm affected the Caribbean and Central America, parts of which were still reeling from Eta just weeks before. At least 45 people died, with dozens more reported missing in the wake of the storm, according to the Herald Mail.

Stromboli's wrath

The Italian volcano Stromboli is one of the most active volcanoes on Earth; it's been erupting continuously for around 2,000 years, according to Oregon State University. Most of the activity is minor — gaseous explosions and burbles of lava that spout above the volcano's rim. Occasionally, though, Stromboli lets off a bigger rumble. This happened in November, when a large explosion sent a column of ash into the air and an avalanche of pyroclastic flow — hot ash and gas — sweeping down the volcano's slopes.

Related: The 11 biggest volcanic eruptions in history

Explosive Etna

Ending 2020 with a bang, Italy's Mount Etna exploded a stream of glowing lava into the sky on Dec. 14, disrupting air travel temporarily and creating an impressive show of geological power. According to Volcano Discovery, ejections of ash continued into the next day, sending a plume 13,000 feet (4,000 m) skyward.

Historians and ancient chroniclers have noted Etna's unrest going back to at least 1500 B.C., according to the Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program, though the volcano's eruptive history stretches back well before that. The volcano has likely been active for some 500,000 years. Most of Etna's eruptive activity doesn't threaten the population centers around it, but there have been major exceptions. In 1928, for example, the town of Mascali was completely destroyed by lava flows. Earthquakes associated with the volcano's activity also sometimes threaten the region. For example, in December 2018, a magnitude 4.8 quake shook the city of Catania, injuring about 30 people.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.