We Live in a Cosmic Void, Another Study Confirms

Earth and its parent galaxy are living in a cosmic desert — a region of space largely devoid of other galaxies, stars and planets, according to a new study.

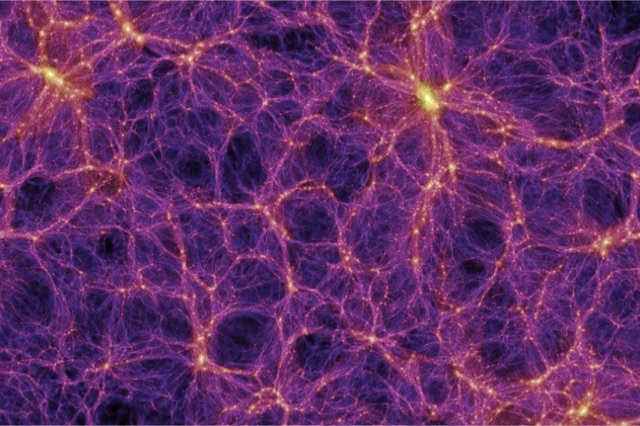

The findings confirm the results of a previous study based on observations taken in 2013. That previous study showed that Earth's galaxy, the Milky Way, is part of a so-called cosmic void. These voids are part of the large-scale structure of the universe, which looks sort of like a block of Swiss cheese, made up of dense filaments containing huge collections of galaxies surrounding relatively empty regions.

The KBC void

The cosmic void that contains the Milky Way's is dubbed the Keenan, Barger and Cowie (KBC) void, after the three astronomers who identified it in the 2013 study. It is the largest cosmic void ever observed — about seven times larger than the average void, with a radius of about 1 billion light-years, according to the study.

The KBC void is shaped like a sphere, and is surrounded by a shell of galaxies, stars and other matter. The new study shows this model of the KBC void is not ruled out based on additional observational data, Amy Barger, an observational cosmologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was involved with both studies, said in a statement from the university.

Barger's undergraduate student who led the study, Benjamin Hoscheit, spoke about their work at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Austin, Texas, on June 6.

Hoscheit sought an efficient way to verify the results of the 2013 study, but in a shorter time span. That work was led by Ryan Keenan, Barger's doctoral student at the time at the University of Hawaii.

Whereas Keenan's work measured the density of different areas of the universe using galaxy catalogs, Hoscheit verified the work using a measurement called the kinematic Sunyaev-Zel'dovich (kSZ) effect, which measures the motions of galaxy clusters within the cosmic web.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The kSZ effect looks at photons coming from the cosmic microwave background (CMB), or light left over from an early stage in the universe's evolution. As the distant CMB photons pass through galaxy clusters, the photons shift in energy. This shift in energy shows how the galaxy clusters are moving, Hoscheit said.

Galaxy clusters that exist in a cosmic void should be attracted to regions with stronger gravity. That would be revealed in how fast these galaxy clusters move through space, Hoscheit said. But if the clusters were moving more slowly than expected, then perhaps the conclusions of the previous study would need to be rethought, he said. However, the kSZ effect on the clusters was consistent with that in the 2013 study, Hoscheit added.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.