Warts and All: Octopus' Skin Bumps Divide Species

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

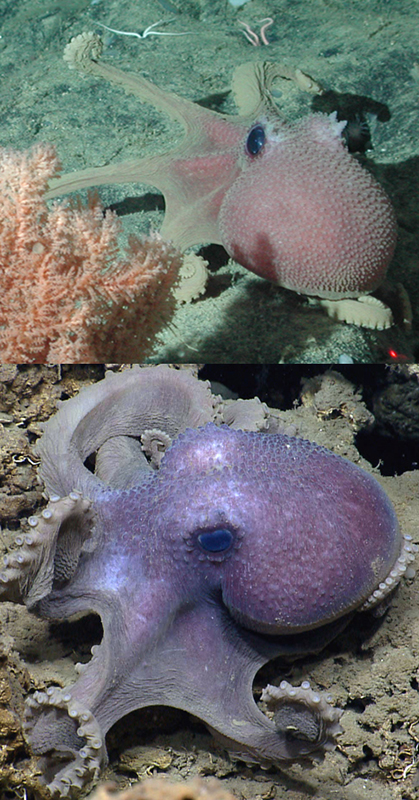

Two species of highly similar deep-sea octopuses are hard to tell apart — unless you look closely at their "warts," a new study finds.

Octopuses in the Graneledone genus are pink and pebbly, with trademark bumps on the skin of their mantles — the bulbous body part resembling a head. Taxonomists have traditionally used the number of warts to differentiate between the species Graneledone pacifica, which lives in the Pacific Ocean, and Graneledone verrucosa, an inhabitant of the Atlantic Ocean. But with limited access to specimens, these warty distinctions didn't always hold up across larger numbers of octopuses, the study authors wrote.

This new investigation, in which scientists analyzed 72 octopuses, is the first to comprehensively examine dozens of G. pacifica and G. verrucosa specimens to determine what about these warts really distinguishes the two octopus species — and the scientists conducted their analysis one wart at a time. [Photos: Amazing Tech Inspired by the Octopus]

Physical features that are unique to a certain animal species can take many forms: the size, shape and number of teeth, distinctive colors or patterns in fur, scales or feathers, the color of an iris, the shape of a thorax or the sweep of a fin, to name just a few. Biologists also listen for vocalizations that no other animal produces, and peer at animals' DNA to tell species apart.

But deep-sea octopus species can be particularly tricky to distinguish, the study's lead author Janet Voight, an associate curator of invertebrates at The Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH) in Chicago, told Live Science.

As with any deep-sea creature, observing and collecting octopuses is challenging, so there are simply fewer individual animals to study and compare, Voight said. Specimens in museum collections — and most of the octopuses in the study were FMNH specimens — can be centuries old, or might have been collected and preserved before DNA analysis was feasible, making it impossible to extract genetic material from their tissues, she said.

"In deep-sea invertebrates, you don't have song, or color, or behavior. You have a specimen preserved for — in some cases — decades," Voight said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"To take that specimen and make it into something that tells us about biology, and about evolutionary history and species distribution and diversity — that takes background knowledge. It's stuff you can't just pick up in childhood being out in nature," she said.

Octopus oddballs

The Graneledone genus is an odd one among octopuses, the study authors wrote. Features that typically distinguish between octopus species in other genera — such as the number of gill membranes and arm suckers, and the shape of a certain organ near the beak — vary too much between Graneledone individuals to be useful, the scientists said in the study.

The researchers gathered their dozens of specimens representing the two species, and hunkered down to count warts. They devised a new method for tracking the distribution of bumps, and eventually pinpointed two characteristics that were consistent across individuals in a given species — how far the warts extended to the tip of the mantle and how far they spread down the arms, Voight said.

They found that the Pacific species had a more extensive covering of bumps, with warts reaching farther down the mantle and dotting its arms to the 10th sucker (counting away from the body toward the arm's tip). By comparison, the bumps on the Atlantic species reached only as far as the sixth and the ninth sucker. And in both species, certain arms and parts of the between-arm webbing had no warts at all — unlike other Graneledone species, the study authors wrote.

"We compared that to all the literature and the reports of all specimens of all the species I had in the genus, and realized that those characters made those two species distinct — and distinct from all others in the genus," Voight told Live Science.

Finding a way to quickly and easily visually differentiate between octopus species could help biologists who encounter potentially new species either on video footage or through brief glimpses in the wild, Voight said. And better data showing where different species are distributed will improve scientists' ability to understand how these elusive animals interact with other marine life, and could inform future conservation efforts, Voight added.

"The better we know what's out there, the better we can protect these unique animals," she said.

The findings were published online today (June 7) in the journal Marine Biology Research.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus