4 never-before-seen octopuses discovered in deep sea off Costa Rica

Enigmatic octopuses that have been newly discovered in the waters off Costa Rica add to a growing registry of deep-sea dwellers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

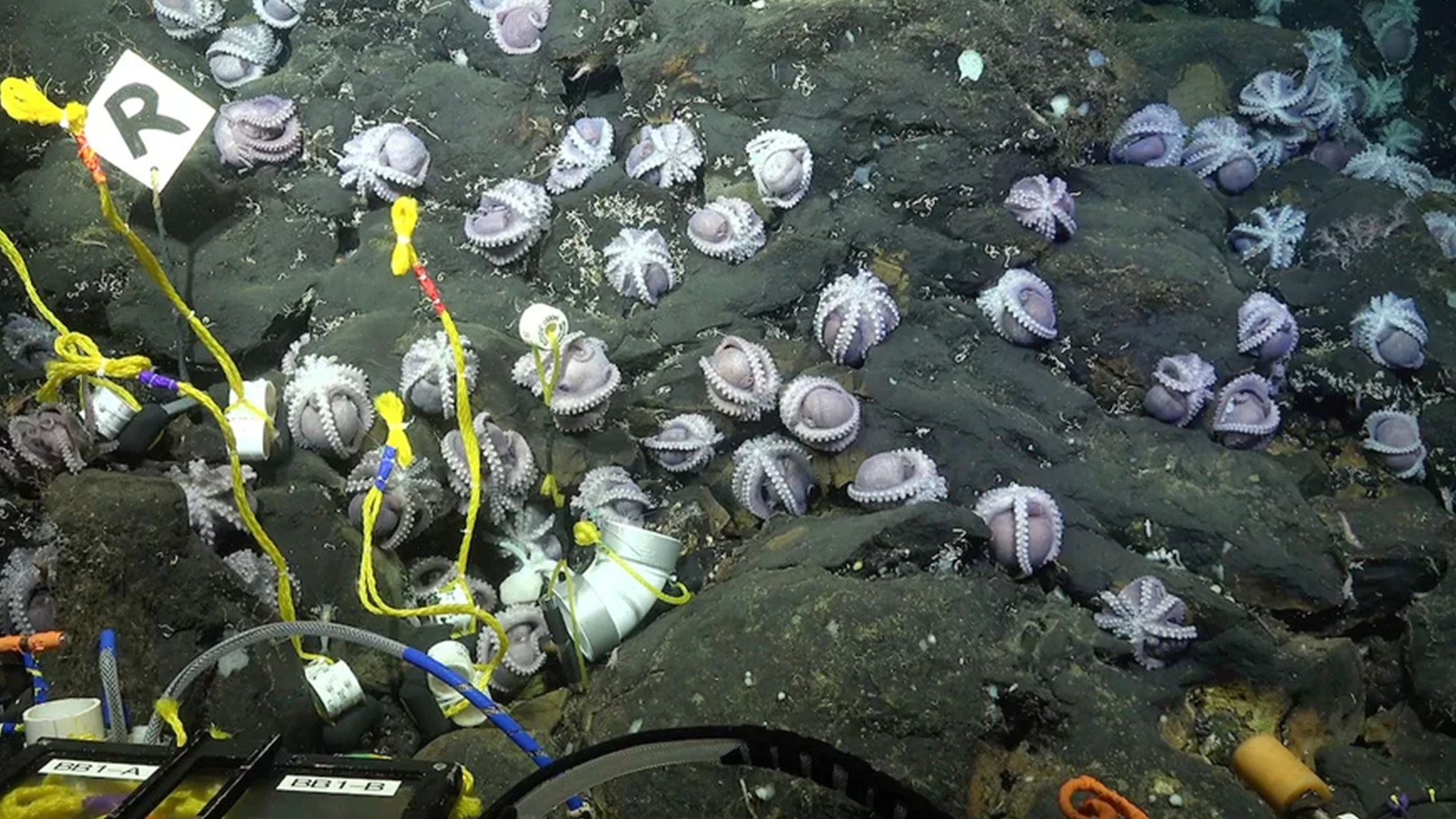

Last month a team of scientists visited an ethereal nursery on the seafloor off Costa Rica, where they watched in awe as a new generation of deep-sea octopuses gently emerged from a quivering cluster of oblong, semitranslucent eggs.

Now the researchers have confirmed these deep-sea dwellers are members of an entirely new, yet-to-be-named species, nicknamed the "Dorado octopus." And they have announced they've discovered three more new deep-sea octopus species on top of that.

"Finding four new species of octopuses on just two expeditions is exciting, revealing some of the rich biodiversity of the deep sea and hinting at how much more waits to be discovered," says Jim Barry, a deep-sea ecologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, who was not involved in the expeditions.

The nursery visit last December was part two of a Schmidt Ocean Institute expedition that took place six months earlier. Then, too, researchers witnessed baby deep-sea octopuses emerge from eggs that their respective mothers were brooding near hydrothermal vents on the same underwater rock formation, called the Dorado Outcrop (hence the new species' nickname). The octopuses' proximity to the vents suggests these creatures may have evolved to use warmth from the seeping hydrothermal fluid to accelerate the incubation process—which is notoriously long for many deep-sea creatures, leaving their offspring vulnerable to predators for extended periods.

The team collected some octopus specimens near the vents and others farther away and brought them to the Zoology Museum at the University of Costa Rica. Fiorella Vásquez, a research assistant at the Zoology Museum, and Janet Voight, associate curator of invertebrate zoology at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, then set out to classify the creatures.

The Dorado octopus is remarkably similar to the pearl octopus (Muusoctopus robustus), which a separate team of researchers previously found brooding eggs near hydrothermal vents off central California. To distinguish the Dorado octopus as a separate species in the recent investigation, the scientists made careful observations and descriptions of the different octopuses, such as measuring their arms and enumerating their suckers. "The two species share an unusual morphology, having smallish eyes, a robust body and fairly short arms," Voight explains. "It's the details that separate them."

Of the three additional species the team identified farther from the hydrothermal vents, two are also members of the genus Muusoctopus. They have double rows of suckers on their arms and lack an ink sac––other traits that are characteristic of the genus.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"But they look really different," Voight says of these two species. For both, large eyes are the most obvious difference from the Dorado octopus. And one of the species is reddish, with long arms, while the other has a lighter shade on its top side and a darker one underneath.

The fourth species is an oddball. "It was just so unlike anything I had seen; I didn't know where to assign it," Voight says. But she and Vásquez observed a single row of suckers on each of the animal's arms and strange bumps on its skin, which they say could place this species in the genus Graneledone. Voight notes, however, that "its bumps aren't quite like what I expected to see, and it's really pale-colored, so it's a bit of an enigma."

These three other newfound species are also officially nameless so far. The researchers collected additional specimens that they're still poring over to determine the best classifications. Subsequently they'll have to meticulously describe and illustrate each species, run that information through peer review and then, if accepted, the species names will enter the scientific literature.

"We have so much to explore in the deep ocean, and part of that exploration is to find new species," Vásquez says. "Every step we take to learn a little more about what is at the bottom of our ocean will help us to conserve it."

The expedition also identified a rare deep-sea skate nursery — which the scientists are calling Skate Park — and three new hydrothermal springs. Expedition co-leader Jorge Cortés-Núñez, a professor emeritus of biology at the University of Costa Rica, says "we have samples and data for many years to come, motivation to continue along that line of research, and powerful information and images to justify the protection and conservation of the deep sea, not only of Costa Rica but of all the ocean."

This article was first published at Scientific American. © ScientificAmerican.com. All rights reserved. Follow on TikTok and Instagram, X and Facebook.

Ashley Balzer Vigil writes about astrophysics for NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center by day and moonlights as a freelance environmental writer.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus