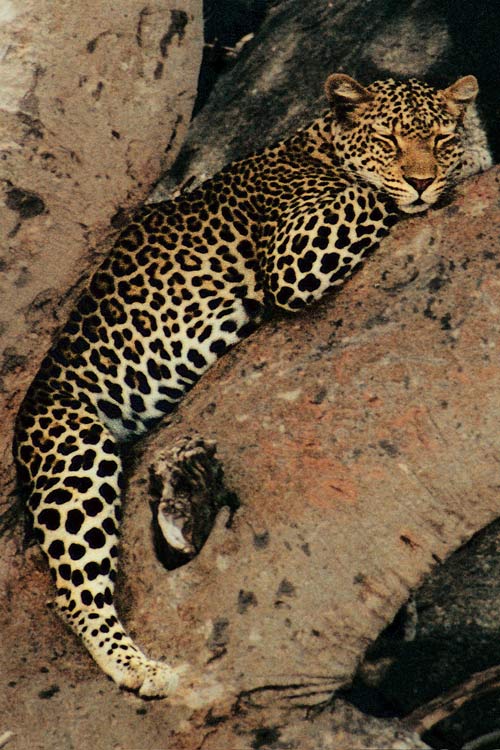

How a Leopard Changes its Spots

As a leopard kitten matures into a prowling adult, its baby spots morph into more commanding rosette markings. Now scientists think they have uncovered the mechanism behind the transformation.

Biologists have long wondered how leopards and other mammals acquired their distinct and uniform coat patterns. In 1952, British mathematician Alan Turing developed an equation to explain how simple chemical reactions produce the spots, stripes, and swirls that decorate a variety of mammals.

But Turing's model couldn't account for the evolution of markings from infant to adult.

To crack the mystery, Sy-Sang Liaw and Ruey-Tarng Liu of National Chung-Hsing University in Taichung, Taiwan, and Philip Maini of Oxford University's Mathematical Institute, modified Turing's model.

"Here, we look at the development from one pattern to another, just as Turing envisioned in his classical 1952 paper," Maini told LiveScience.

The researchers assumed, like Turing, that when a leopard or jaguar is born, its skin contains pigment cells, which secrete two chemicals into the skin's upper layer. The two chemicals, called morphogens, are thought to diffuse out from the pigment cells and interact to produce either a black-brown color or a pale yellow-reddish color.

With a complex computer model, the researchers created a two-stage process, each stage having different governing rules. In order to account for an animal's growth, the second stage included parameters, such as diffusion rate and a scaling factor, which change during the computer simulation.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"How chemicals diffuse is a very difficult question in biology because the material through which chemicals are transported [such as cells and tissues] is highly non-uniform," Maini said.

They found that the concentration of these diffusing chemicals in the skin determines the exact markings on an adult leopard or jaguar. "These [morphogens] would be proposed to be in the skin, and the pattern in the hair or the fur would be determined by the morphogen concentration in the skin," Maini said.

Scientists have yet to detect these morphogens within an animal's skin. So the next step in understanding a leopard's spots will be to pinpoint the color-coding chemicals.

The research was detailed last month in the journal Physical Review E.

- Top 10 Deadliest Animals

- How a Zebra Lost Its Stripes

- The Real Reason Animals Flaunt Size and Color

- Elusive Snow Leopards Photographed

- World's Ugliest Animals

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.