Can Water Naturally Flow Uphill?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Earth's gravity is strong, but can water ever naturally go against it and flow uphill?

The answer is yes, if the parameters are right. For instance, a wave on a beach can flow uphill, even if it's for just a moment. Water in a siphon can flow uphill too, as can a puddle of water if it's moving up a dry paper towel dipped in it.

Even more curiously, Antarctica has a river that flows uphill underneath one of its ice sheets. So, how does science explain these upward watery movements? [Where Did Earth's Water Come From?]

Waves and siphons

Waves (powered by wind), tides (primarily caused by the moon's gravitational forces) and tsunamis (often triggered by earthquakes and underwater landslides or volcanoes) can cause water to go against gravity. The energy and forces produced by these natural phenomena can push water upward, allowing it to naturally rise into a wave or run up a shoreline.

A siphon acts under different pressures. People have used siphons since ancient times; the ancient Egyptians used siphons for irrigation and winemaking, according to a study published in 2014 in the journal Scientific Reports. Nowadays, thieves might use siphons to steal gas from cars. However, there is still debate about how siphons work.

You can visualize a siphon by thinking of two cups connected by a tube shaped like an upside-down "U." The water-filled cup sits on a stair, and an empty cup sits below it. If an experimenter puts one end of the tube into the water-filled cup and sucks the air out of it as you would when using a straw, that will allow the water to flow into the tube.

A siphon is created once the water flows up one side of the tube and down the other, into the empty cup.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Siphons also work in vacuums, so it doesn't appear that atmospheric pressure is at play, according to a 2011 study in the Journal of Chemical Education. Rather, gravity and molecular cohesion appear to be involved, according to a 2015 study in the journal Scientific Reports.

Gravity accelerates the water through the "down" part of the tube, into the lower cup. Because water has strong cohesive bonds, these water molecules can pull the water behind them through the uphill portion of the tube, according to Wonderopolis, a site where daily questions get answered.

However, many liquids that do not have strong cohesive bonds still work in siphons, so it's unclear exactly how siphons work in different cases, according to Wonderopolis.

Capillary action

What about the paper towel example? This action, called capillary action, allows small volumes of water to flow uphill, against gravity, so long as the water flows through narrow and small spaces.

This upward flow happens when a liquid's adhesion to the walls of a material, such as the paper towel, is stronger than the cohesive forces between its liquid molecules, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

In plants, water molecules are drawn up capillaries called the xylem, helping the plant to draw in water from the soil, the USGS said. [Are Trees Vegetarian?]

Antarctica river

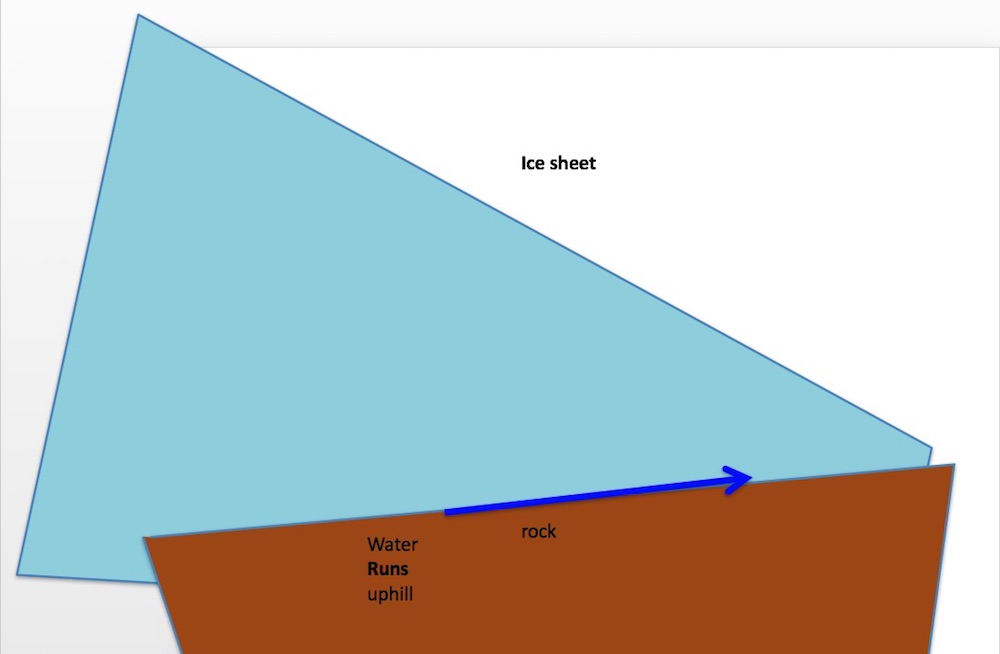

There's a river that flows uphill beneath one of Antarctica's ice sheets, according to Robin Bell, a professor of geophysics at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in New York.

Beneath the continent's ice sit the Gamburtsev Mountains, a massive range with peaks and valleys that are about the same size as the European Alps, she said. "In the valleys, there is water," Bell told Live Science. "We can tell because when we fly over it, the echo from the [ice-penetrating] radar is much stronger."

Intriguingly, researchers can tell that the river is flowing backward because the ice on top of it is aligned against the direction of the ice flow, Live Science reported previously. This alignment and the enormous pressure from the ice sheet above it push the water uphill, Bell said.

"We realized that the ice is forcing the water up the hill, squeezing the water backward," Bell said.

There are other instances in which water has naturally run uphill. For example, an 8.0-magnitude earthquake shook southeastern Missouri so hard that the Mississippi River temporarily flowed backward, Live Science previously reported. In addition, a 2006 study in the journal Physical Review Letters showed that small amounts of water put on a hot surface — a scalding pan, for instance — can "climb" tiny stairs made out of vapor if the water is hot enough, Live Science reported.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus