2013 Hurricane Season Ends with a Whimper

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

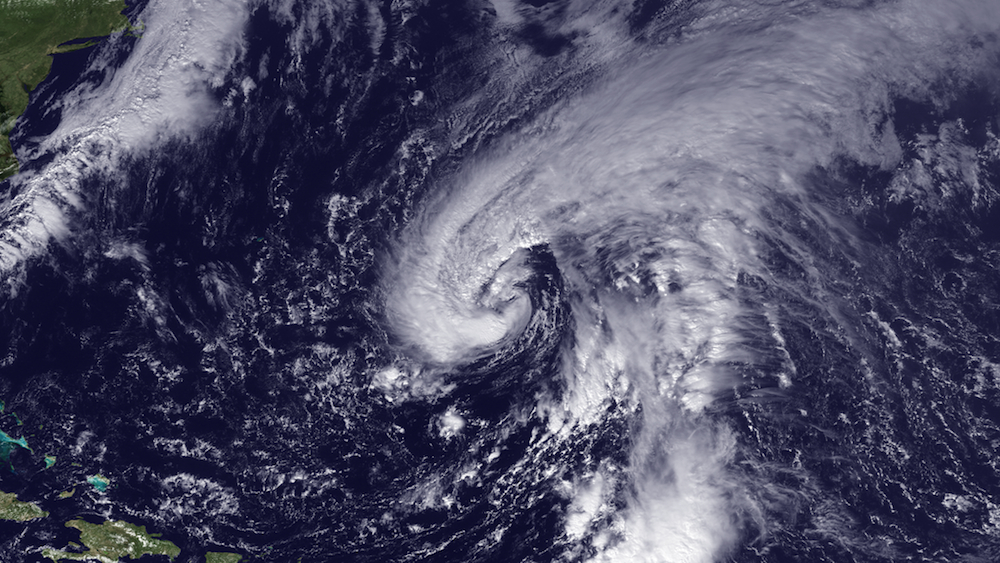

Despite predictions for an above-average hurricane season, all was quiet along the Atlantic Coast this year.

For most of 2013's premier hurricane months — August through October — an unusual weather pattern in the Atlantic tore apart budding tropical storms, preventing hurricanes from forming and wreaking havoc with forecasts. The lack of strong storms makes this year's hurricane season, which ends Saturday (Nov. 30), one for the record books.

Faulty forecasts

The weather pattern, which featured exceptionally dry air and strong wind shear, had already established itself in August, when the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issued a forecast that said climate conditions called for a 70 percent chance of an above-normal storm season. NOAA forecast three to five major hurricanes and 13 to 20 named storms (tropical storms and hurricanes). But NOAA wasn't the only one fooled; other climate modelers, such as those at Colorado State University, also predicted several major hurricanes.

"Like all of the seasonal forecasts this year, [the NOAA forecast] wasn't very accurate," said Brian McNoldy, a tropical weather researcher at the University of Miami's Rosentiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science. "The 2013 season was decidedly well below normal," he told LiveScience in an email interview.

And the hurricane-preventing pattern never disappeared. By November, only two of the season's 13 named storms had become hurricanes: Ingrid and Humberto. And both were barely even hurricanes, with wind strengths just above the 74 mph (119 kph) hurricane threshold. No storm in the Atlantic ever came close to achieving major hurricane status, defined as Category 3 — wind speeds greater than 111 mph (178 km/h).

The season also nearly set a record for the slowest start, as Humberto strengthened into a hurricane mere hours before Sept. 11, the date of the latest first hurricane on record. [Hurricane Season 2013: Storm Coverage]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

No major storms

This year marked a big turnaround from 2012, when the number of tropical storms exceeded NOAA's annual forecast and Hurricane Sandy (which was actually a post-tropical cyclone when it made landfall) ravaged the Atlantic Coast.

On average, 12 Atlantic tropical storms have formed each year since 1981, and six or seven of those disturbances have strengthened into hurricanes. Two of those hurricanes, on average, will intensify into major hurricanes. And hurricane activity has been higher than average since 1995, said Gerry Bell, NOAA's lead seasonal hurricane forecaster.

But 2013 was the slowest hurricane season in 30 years, as well as the sixth-least-active storm year since 1950, in terms of collective strength and duration of named storms and hurricanes, NOAA said. The agency had predicted Accumulated Cyclone Energy, or ACE, of 120 percent to 205 percent of the 1950-2005 median for 2013. A measure of the intensity of a hurricane season, ACE quantifies the amount of energy contained in cyclonic winds, taking into account the number, duration and intensity of storms. Instead, the 2013 season ends with an ACE at 30 percent of the 1981-2010 median, according to Colorado State University's end-of-year hurricane report.

The Pacific tropical storm season will finish close to average, with five super-typhoons (four to five are expected each year) and an ACE of 94 percent of average, McNoldy said. (The term typhoon refers to tropical cyclones in the Northwest Pacific, while hurricane is used for storms in the Atlantic and Northeast Pacific.)

Just one tropical storm, Andrea, made landfall in the United States this year, causing one death, according to NOAA. It's now been eight years since a major hurricane hit the United States, the longest break on record, according to NOAA.

Atmospheric desert

Weather experts say the Atlantic's failed forecast is due to an unpredictable weather pattern in the ocean basin's hurricane birthing grounds, which kept 2013's tropical disturbances from growing into monster storms.

"The suppression of hurricane activity was linked to an atmospheric pattern that created exceptionally dry air and wind shear from the U.S. all the way to Africa," Bell told LiveScience.

The persistent weather tamped down hurricanes in two ways, Bell explained. First, there was not enough moisture for storms to build towering thunderclouds, the harbinger of hurricanes. Second, strong winds blowing in different directions at different heights in the atmosphere, a phenomenon called wind shear, tore apart budding storms. Dusty air streaming westward from Africa also played a minor role in destroying storms, Bell said. [Storm Season! How, When & Where Hurricanes Form]

Bell said the dry air and wind shear are not linked to global warming or other predictable climate patterns. "We've seen this type of thing before, just not very often," Bell said. "It's part of natural climate variability."

Ongoing research, such as flights into storms this summer by NASA's Global Hawk drones, may help illuminate why there was so much dry air to choke off tropical systems.

"There were other factors at play that forecast teams can learn from with the benefit of hindsight," McNoldy said. "There was a lot of dry air across much of the basin, but the reasons for why that dry air was so persistent are unclear so far."

A look ahead

Bell emphasized that this year's peace does not mean the Atlantic is heading into a quiet storm cycle.

The climate conditions that favor an active hurricane season still exist in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, he said. Sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic are warmer than average, and there is no El Niño in the Pacific driving high-altitude winds that can create wind shear in the Atlantic.

"We are still in a high-activity era," Bell said. "I think the most important thing is that people along coastal regions do not become complacent, and [instead] prepare each and every hurricane season. It only takes one hurricane striking your region to make it a very bad year."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus