Tahiti Abounds in New Beetle Species

Dozens of new beetle species have been discovered in Tahiti, adding to the long list of unique insects known to crawl among the island's rich biodiversity .

Though Tahiti looks like a speck on a map of the South Pacific — spanning only about 28 miles (45 Kilometers) at its widest point — its steep, lush cliffs teem with some of the most diverse insect populations in the world.

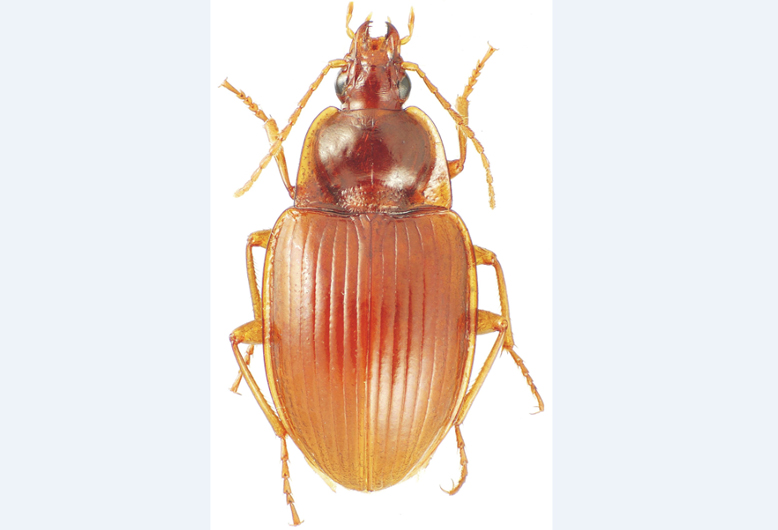

A group of entomologists interested in updating Tahiti's species classification records recently embarked on a month-long survey, and returned with 600 ground-dwelling beetles — those that have lost their flight wings through evolution. [See Photos of New Tahitian Beetles]

The collection included more than 40 new species, 28 of which are described for the first time this month in the journal ZooKeys.

Tahiti's insect diversity results, in part, from its jagged terrain, which keeps insect populations separate by preventing them from mating.

"If you are on a ridge, and your cousins are on another ridge, and you can't fly to the next ridge, then you are stuck," said Jim Liebherr, an entomologist at Cornell University who led the beetle component of the expedition. "So everyone stays home, and the population has the opportunity to diverge."

The island also has large patches of unstable soil, which easily become dislodged and fall away with rain forest rainstorms, contributing to the fragmenting and isolating of insect populations that eventually evolve into distinct species.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To locate these disparate populations, the team hiked into densely forested areas, some that were only accessible at helicopter drop-off points. Many of the sites had been visited by local Tahitians, but never before by researchers.

"Until we know what's there, we are blind," Liebherr said. "So this is basically our first step."

Ground-dwelling beetles are small — measuring between 3 to 8 millimeters (0.1 to 0.3 inches) long — and can be difficult to see on a shaded forest floor. To collect them, the team sprayed foliage near the ground with an organic chemical that causes insects to become more active, and crawl out from under hiding places in leaves and ferns. The team then laid down a white nylon sheet where the insects gathered.

The researchers chose to use the chemical — which breaks down within three days — rather than physically sifting through the moss-filled forest floor to minimize their footprint on the island.

"These thick mosses are quite old, and our desire to conserve the natural habitat requires use of non-intrusive collecting techniques," Liebherr said. "Even beating such a moss mat would dislodge it from its supporting plant, destroying this patch of habitat."

After the expedition, Liebherr traveled to the Paris Natural History Museum to compare his specimens with the largest collection of Tahitian ground-dwelling beetles worldwide. Aside from looking for obvious differences in the exterior shape of the body and the distribution of hairs, he also dissected and compared genitals — often a distinct indicator of beetle species — to figure out which of his beetles represented new species.

Liebherr said he hopes the work will provide a helpful baseline for future ecological studies on the island, but he knows that many more beetles likely remain undiscovered.

Given the amount of time we had, we did quite well," Liebherr said. "Did we finish? Absolutely no way."

He also pointed out that, of the 108 ground-dwelling beetle species known from the region, 42 are known only from single specimens.

"This shows how much more needs to be done to adequately classify the diversity of these islands," Liebherr said.

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow LiveScience on Twitter, Facebookand Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus