Photos: Zombie Beetles Hang from Flowers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Zombie beetles

Just before a deadly fungus kills the goldenrod soldier beetle, it instructs the beetle to climb a plant and clamp its mandibles around a flower. Then, after the beetle dies, the fungus prompts the dead beetle to raise its wings, making it a spooky zombie.

The spread wings help expose and spread fungal spores and likely attract healthy living beetles, according to the study was published in the September issue of the Journal of Invertebrate Pathology.

"I compare this to human zombies — dead bodies that can move," said study lead investigator Donald Steinkraus, a professor of entomology at the University of Arkansas. "It would be like a dead human suddenly standing up and opening its arms." [Read the Full Story about the Zombie Beetles]

Goldenrod soldier beetle

The goldenrod soldier beetle (Chauliognathus pensylvanicus) is a common sight in Arkansas during September and October. They eat pollen, making them key pollinators.

The beetles' larvae eat pests, such as other insects and possibly even ticks, Steinkraus said.

Dead and spread

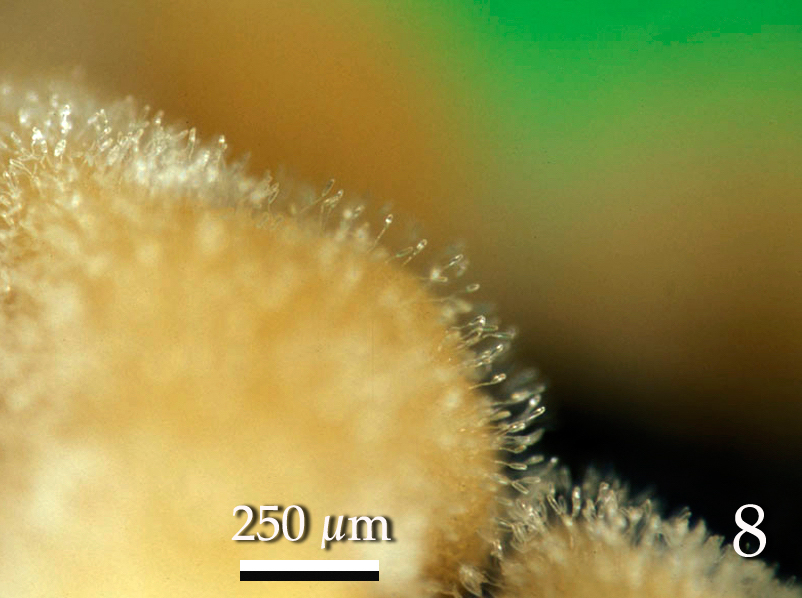

Researchers found a curious scene: hundreds of dead beetles, wings spread, hanging by their mandibles from flowers. The furry, yellow sacs are the fungus that has emerged from the beetles' insides.

RIP beetle

After the fungus infects a beetle, it takes about two weeks for it to kill its host. Then, it orders the beetle to climb a plant and attach itself to a flower by biting down with its mandibles. The beetle dies shortly after.

Open wings

About 15 hours to 22 hours after death, the beetle's wings open, which helps spread the fungal spores to other beetles.

Fungal spore

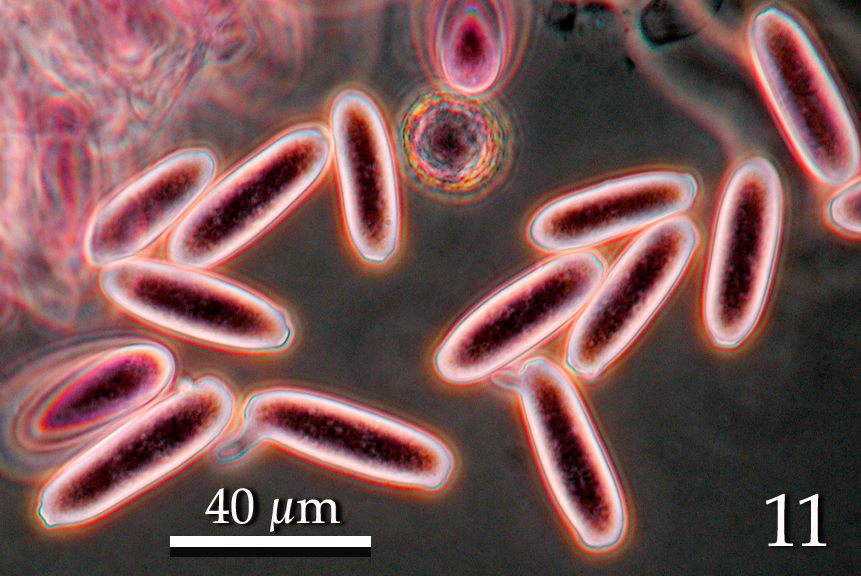

The spore of the fungus Eryniopsis lampyridarum that emerged from the insides of a host soldier beetle.

Spores up close

The fungus makes two types of spores. Here is a magnification of the primary spores, which have long, tapering ends. These spores infect soldier beetles in the fall.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

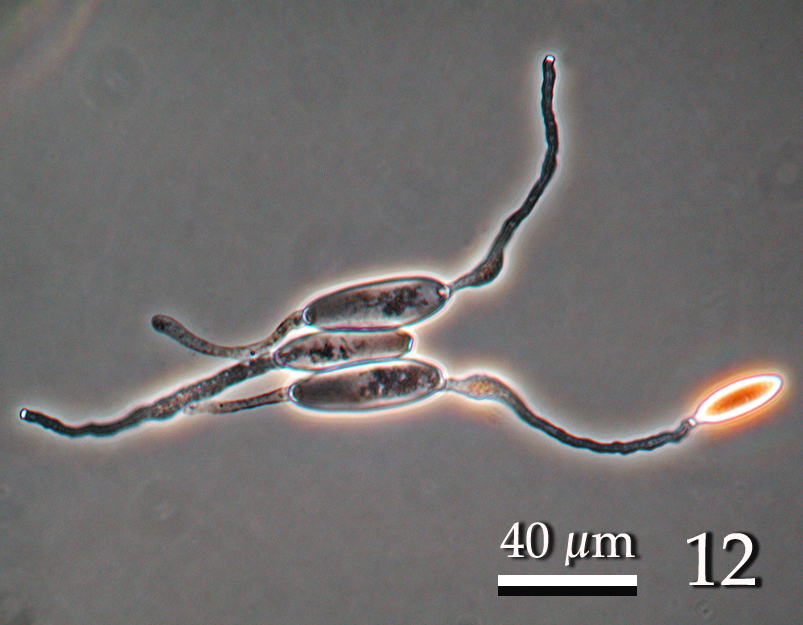

Secondary spores

Once inside the beetle, the primary spore gives rise to secondary spores, known as resting spores.

"These beetles are not attached by their mandibles, but die on the ground, where the resting spores are scattered about on the soil, overwinter, and infect new soldier beetles the following summer," Steinkraus said.

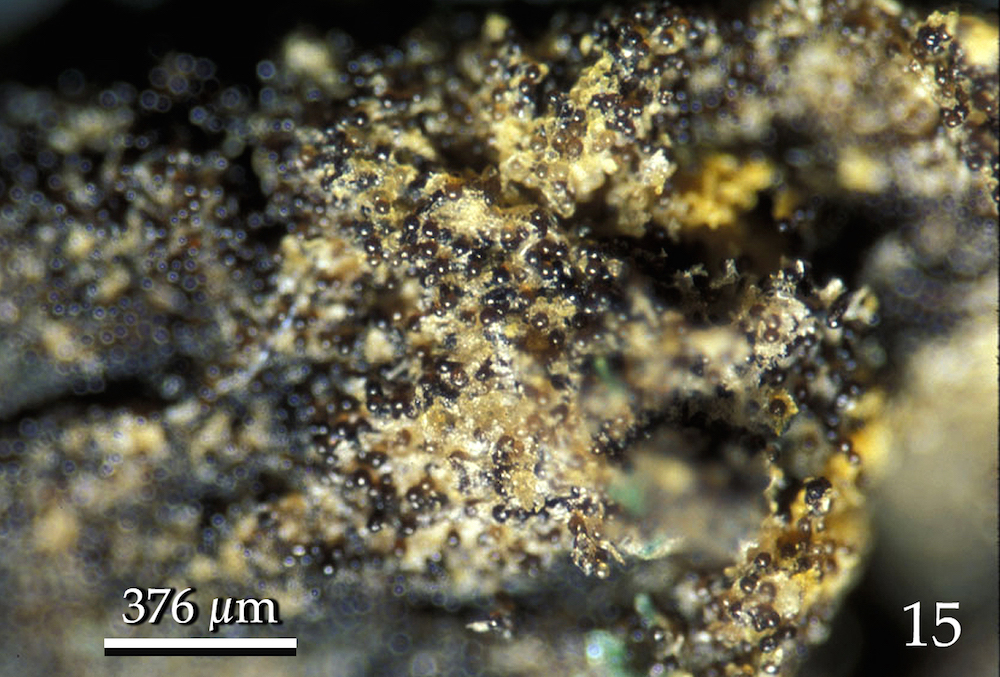

Magnified resting spores

The dark brown mature resting spores of E. lampyridarum. These spores were removed from the abdomen of an infected soldier beetle.

[Read the Full Story about the Zombie Beetles]

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus