Why haven't all primates evolved into humans?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

While we were migrating around the globe, inventing agriculture and visiting the moon, chimpanzees — our closest living relatives — stayed in the trees, where they ate fruit and hunted monkeys.

Modern chimps have been around for longer than modern humans have (less than 1 million years compared to 300,000 for Homo sapiens, according to the most recent estimates), but we've been on separate evolutionary paths for 6 million or 7 million years. If we think of chimps as our cousins, our last common ancestor is like a great, great grandmother with only two living descendants.

But why did one of her evolutionary offspring go on to accomplish so much more than the other? [Chimps vs. Humans: How Are We Different?]

"The reason other primates aren't evolving into humans is that they're doing just fine," Briana Pobiner, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C., told Live Science. All primates alive today, including mountain gorillas in Uganda, howler monkeys in the Americas, and lemurs in Madagascar, have proven that they can thrive in their natural habitats.

"Evolution isn't a progression," said Lynne Isbell, a professor of anthropology at the University of California, Davis. "It's about how well organisms fit into their current environments." In the eyes of scientists who study evolution, humans aren't "more evolved" than other primates, and we certainly haven't won the so-called evolutionary game. While extreme adaptability lets humans manipulate very different environments to meet our needs, that ability isn't enough to put humans at the top of the evolutionary ladder.

Take, for instance, ants. "Ants are as or more successful than we are," Isbell told Live Science. "There are so many more ants in the world than humans, and they're well-adapted to where they're living."

While ants haven't developed writing (though they did invent agriculture long before we existed), they're enormously successful insects. They just aren't obviously excellent at all of the things humans tend to care about, which happens to be the things humans excel at.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We have this idea of the fittest being the strongest or the fastest, but all you really have to do to win the evolutionary game is survive and reproduce," Pobiner said.

Our ancestors' divergence from ancestral chimps is a good example. While we don't have a complete fossil record for humans or chimps, scientists have combined fossil evidence with genetic and behavioral clues gleaned from living primates to learn about the now-extinct species whose descendants would become humans and chimps.

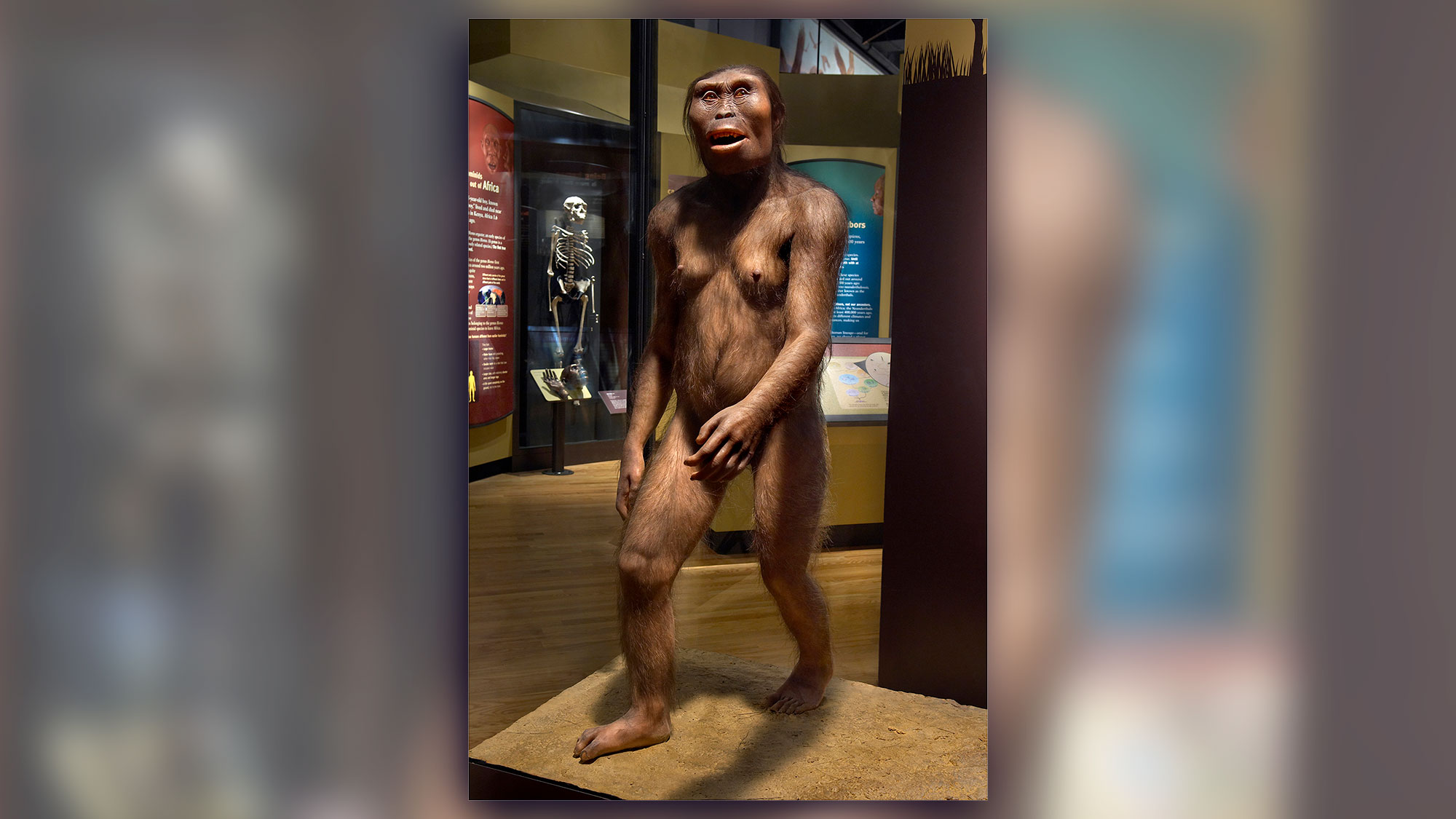

"We don't have its remains, and I'm not sure if we'd be able to place it with certainty in the human lineage it if we did," Isbell said. Scientists think this creature looked more like a chimpanzee than a human, and it probably spent most of its time in the canopy of forests dense enough that it could travel from tree to tree without touching the ground, Isbell said.

Scientists think ancestral humans began distinguishing themselves from ancestral chimps when they started spending more time on the ground. Perhaps our ancestors were looking for food as they explored new habitats, Isbell said.

"Our earliest ancestors that diverged from our common ancestor with chimpanzees would have been adept at both climbing in trees and walking on the ground," Isbell said. It was more recently — maybe 3 million years ago — that these ancestors' legs began to grow longer and their big toes turned forward, allowing them to become mostly full-time walkers.

"Some difference in habitat selection probably would've been the the first notable behavioral change," Isbell said. "To get bipedalism going, our ancestors would have gone into habitats that didn't have closed canopies. They would have had to travel more on the ground in places where trees were more spread out."

The rest is human evolutionary history. As for the chimps, just because they stayed in the trees doesn't mean they stopped evolving. A genetic analysis published in 2010 suggests that their ancestors split from ancestral bonobos 930,000 years ago, and that the ancestors of three living subspecies diverged 460,000 years ago. Central and eastern chimps became distinct only 93,000 years ago.

"They're clearly doing a good job at being chimps," Pobiner said. "They're still around, and as long as we don't destroy their habitat, they probably will be" for many years to come.

- Could Evolution Ever Bring Back the Dinosaurs?

- Why Humans Outlive Apes

- Why Do Some Animals Eat Their Own Poop?

Originally published on Live Science.

Grant Currin is a freelance science journalist based in Brooklyn, New York, who writes about Life's Little Mysteries and other topics for Live Science. Grant also writes about science and media for a number of publications, including Wired, Scientific American, National Geographic, the HuffPost and Hakai Magazine, and he is also a contributor to the Discovery podcast Curiosity Daily. Grant received a bachelor's degree in Political Economy from the University of Tennessee.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus