Seafloor Surveys Shed Light on Deadly Haiti Quake

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Marine evidence from the deadly 2010 Haiti earthquake is shedding light on how it happened, and could help assess the risk this and other areas face, researchers say.

The catastrophic magnitude-7.0 temblorstruck two years ago yesterday, on Jan. 12, 2010. It killed more than 200,000 people and left more than 1.5 million homeless, with damage estimated at about $8 billion.

As destructive as the quake proved, it barely ruptured the surface of the island. This has made it difficult to study and understand what further risks the area might face. Even the faults involved remain unclear — the most likely culprit would seem to be the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden fault, a "strike-slip" fault at the boundary between the North America and Caribbean tectonic plates, where huge slabs of earth grind past each other far below the surface. However, other, previously unknown faults have been implicated as well.

"We really don't know for sure which fault ruptured in the earthquake," said marine geologist Cecilia McHugh at Queens College in New York. "Was it the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden fault, or another structure?"

In addition, the Haiti quake was unusually complex in that there was not only evidence of horizontal motion along the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden faultduring the main shock, but also vertical compression or "shortening" of the land during the aftershocks.

"One would expect in this type of setting that the earthquake will generate lateral motion of the land only, but this one also generated compression and shortening," McHugh said. The fact that this earthquake behaved unusually "makes it hard to predict or construct models for seismic hazard evaluation."

Underwater clues

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

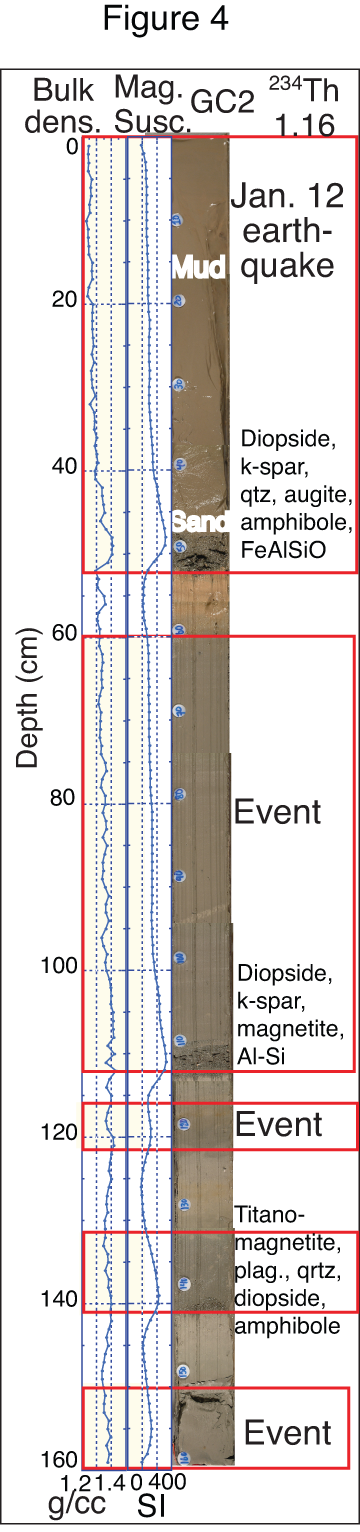

To learn more about the causes of the disaster, McHugh andher colleagues looked underwater off the coast of Haiti immediately after the quake. They analyzed the water column and drilled out long cylinders of mud and sand from the seafloor.

The researchers found the quake generated vast landslides, driving large amounts of earth sliding into the sea from the shore as well as from shallower to deeper portions of the Canal de Sud off the island of Hispaniola, of which Haiti is the western half. Nearly two months after the main shock, a 2,000-foot-thick (600 meters) plume of sediment was still present in the lowermost waters at this location, revealing just how powerful the quake was. [Looking Back: Images from the Haiti Earthquake]

"A similar situation was found three months after the 2004 Sumatra earthquake by submarine dives conducted by our Japanese colleagues," McHugh recalled. "These large-scale events really disturb life, the water column and sediments."

All in all, more than 19 square miles (50 square kilometers) of the underwater basin was covered with sediment about 3 feet (1 m) thick. The landslides also caused water to slosh back and forth, generating a small tsunamithat killed several people.

Older quake revealed

The researchers saw that much of the landslides associated with the 2010 Haiti quake occurred near an area where the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden fault bends. "This bend may be related to the shortening that occurred in the 2010 earthquake," McHugh noted, shedding light on the quake's complex nature — they know the aftershocks were located there as well.

The core samples also revealed a second and much older quake. "Our findings of a 2,000-year gap in-between earthquakes in this region raise the question that shortening and uplift associated with the unusual 2010 earthquake may also have occurred 2,000 years ago," McHugh said, findings that could help tease apart how such rare quakes might work.

The work in Haiti could help decipher what happens in other areas where comparable activity might occur, such as the San Andreas Faultin California, another "strike-slip" fault that has also had similar earthquakes that did not break the surface. Other submarine environments they are investigating to see how often earthquakes recur include the Sea of Marmara near Turkey, the Ionian Sea near Greece and the trench near the epicenter of the 2011 Japan earthquake.

"We are also beginning work in Bangladesh — with a population of 200 million people and most living near the coast, the risk of earthquakes and tsunamis is tremendous," McHugh said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the August issue of the journal Geology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus