Build Your Own Moon: Online Lunar Game Nabs Honors

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An online game that allows players to build their own moon and sculpt its features has won big praise in science art competition.

The game, called "Selene: A Lunar Construction GaME," measures how and when players learn as they discover more about how the Earth's moon formed and, by extension, the solar system. It received an honorable mention in the 2012 International Science & Engineering Visualization Challenge, the journal Science announced today (Jan. 31).

As players experiment with the game, they learn more about one of the easiest heavenly bodies they can study, Selene developers said.

"The moon is the only body in the entire universe that we on Earth can look at with the unaided eye," Debbie Denise Reese, principle investigator of the overarching Cyberlearning through Game-based, Metaphor Enhanced Learning Objectives (CyGaMEs) project, told SPACE.com. "When they look at the moon, players are seeing what actually created those features."

No longer are the dark plains and overlapping craters a mystery.

"It makes moon observations more meaningful," Reese said.

Build your own moon

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

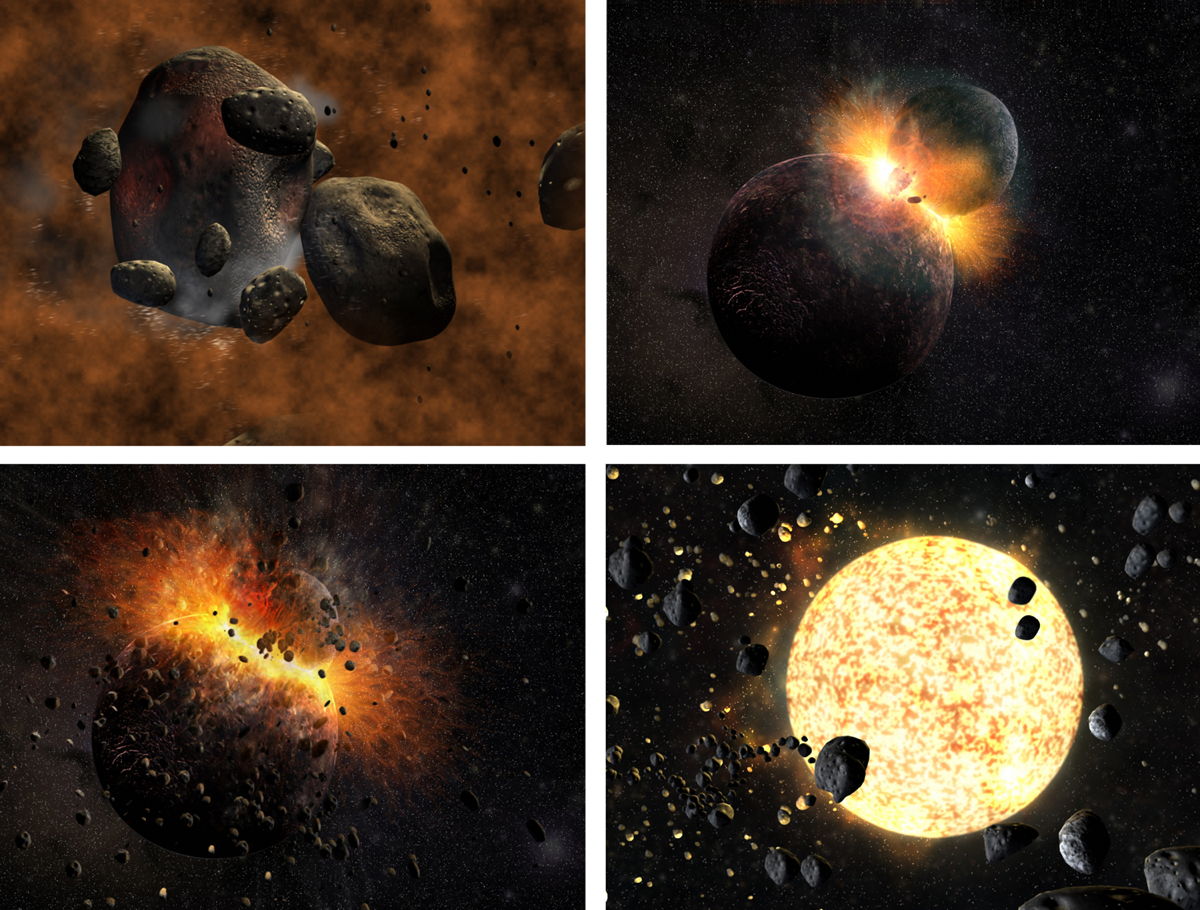

Named for the Greek goddess of the moon, Selene works in two parts. In the first round, players aim asteroids of varying sizes, densities, and radiations so that they collide with one another. Too much force, and the rocks ricochet off one another. [How Earth's Moon Formed (Video)]

But even if you overshoot your target, the gravity of the growing moon may tug just enough to pull the new piece into the pack, giving participants a chance to watch accretion in action. The developing moon is constantly compared to the real-life one, and players strive to make as close a match as possible.

After all of the small asteroids have melted together to form a smooth new moon, it's time to scratch up the surface. Players can aim asteroids of varying sizes at the body, and select areas where lava breaks through the crust. Again, the time range is compared to Earth's moon, with spikes and dips in bombardment and lava flow that the player must work to emulate.

"Playing Selene could be tied to eyeball observations of the moon at night," Charles 'Chuck' Wood, Executive Director of the center for Educational Technologies at Wheeling Jesuit University in West Virginia, told SPACE.com by email.

"The dark smudges and bright pinpricks would become understandable as massive lava flows and impact craters because the player had virtually created the same features."

With almost 50 years of planetary science experience, Wood served as the content expert for the project. According to Reese, one of the goals was "to transfer what's inside his head into procedural activities that players can do."

Because the accretion and surface-sculpting processes for the moon echo that of the rest of the planets, players also develop an understanding of how the early solar system formed.[New Ideas About the Moon-Forming Impact (Video)]

As kids ages nine and up engage in the game, they build concrete knowledge that can be applied into any learning environment that they later experience, a process that serves to make learning more intuitive, according to Reese.

Though the game is effective for high school and college students, and slanted to match the national standards for those age ranges, Reese said that it was more attractive to middle school students. By the time students hit upper educational levels, they are either more focused directly on their studies, or more attracted by high-action games, such as first person shooters.

But when it comes to 9- to- 14-year-olds, Reese said, "they just eat this up."

Learning about learning

As players engage in discovering just how a moon is shaped, Reese and other scientists are engaged in finding out more about how those players learn. One of the primary goals of Selene is to allow Reese and her team to analyze the learning process. That means the game requires a login, and for minors, parental permission must be given.

Although a thorough analyzation takes time, Reese was able to provide a quick overview of my game play while I spoke to her by phone, something I wasn't expecting. She took the time to analyze how quickly I learned from my failures, and point out not only where I struggled but also when I was immersed in the game.

"I wasn't with you, but I can tell from looking at your data what your experiences were," she said.

That under-the-hood ability to study learning is why the project was so attractive in terms of funding to NASA and the National Science Foundation, Reese said.

The idea for Selene first took hold in the summer of 2006, and a prototype of the game was developed by CyGaMEs in May of 2007. The first version was released in 2010. But the game is constantly being improved as the understanding of the learning process grows. The team is also looking at expanding it to mobile platforms in the near future.

"The knowledge that we receive through the CyGaMEs project and using Selene as a research environment helps us to create instructional games across all disciplines," Reese said.

But that knowledge wasn't something that could be directly demonstrated to the 2012 International Science & Engineering Visualization Challenge, hosted by the National Science Foundation and the journal Science. Created to emphasize and encourage the growth of science in more visual mediums for education and media purposes, the competition has five categories, one of which is Games & Apps, where Selene placed. There were no first place awards in the Games & Apps category, only honorable mentions.

Both Reese and Wood were excited not only about the award but about the exposure it would provide.

"The recognition is of course a great honor and encouragement — but more importantly, may drive more players to the website so that we can collect more data," Wood said.

Reese agreed. "To have the success that we've had and be able to get the word out is really a great opportunity."

More players, of course, means more information that can be gathered about how participants learn.

At the same time, more people can learn about how the moon formed, growing their understanding of the nearest celestial body.

"It has been rewarding to see students from elementary to college age understand and talk about lunar processes at a much higher level of understanding than in any textbook," Wood said.

To learn more about the Selene game, and build your own moon, visit: http://selene.cet.edu/

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus