Daydreamers: Scientists Find Our Bored Baseline

Bored out of your skull is a reality. A new study of mind wandering shows that the mundane moments of life allow brains to shift into a default resting state that invites daydreaming.

Some psychologists had suggested that mind wandering could be the brain's baseline, a place of flitting thoughts from which a person must wrench away for challenging work.

The new study agrees and looks deeply into the neural mechanics behind this common and sometimes happy affliction.

The findings also offer a solution to those who need to snap to. Rather than muscle-fatiguing efforts to focus, just try switching to more engaging work, said neuroscientist Malia Mason, lead author of the new work.

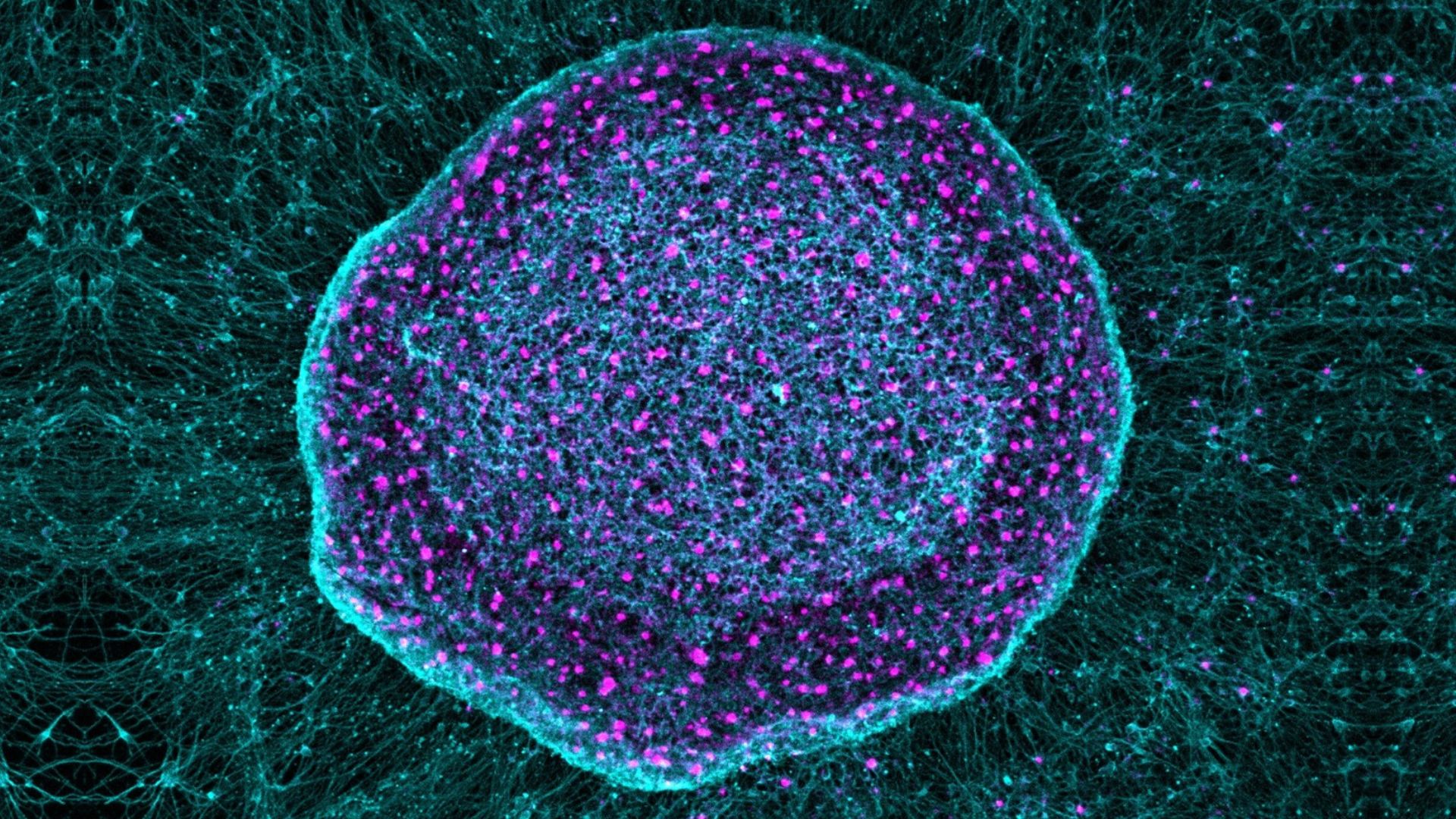

Brain images

How does the mind wander into the la-la-land state we all drop into when the brain spontaneously generates a stream of voices, images, thoughts and feelings?

To find out, Mason, then at Dartmouth College, and her colleagues imaged the brains of a small group of participants performing simple, practiced tasks as well as more challenging, novel activities. The tasks required subjects to recall and manipulate four 4-letter sequences and four finger-tapping patterns.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At random intervals the scientists interrupted participants and asked if they had had any "irrelevant thoughts."

They found that during practiced tasks, the participants showed increased activity in certain regions of the brain's cortex, or the outer layer of grey matter that covers the surface of the brain. When these daydream brain regions lit up, the participants also reported the highest levels of irrelevant thoughts.

Daydream degree

Not all minds wander to the same extent. Individuals who showed more blood flow in the default brain regions also reported more stray thoughts.

Now the scientists want to know why these unfocused thoughts occur at all. One idea is that daydreaming allows a person to stay only as alert as they need be during mundane tasks. The flitting thoughts could also serve as a "spontaneous mental time travel," which helps to thread together a person's past, present and future experiences, suggest the researchers.

Of course, there's one more possibility. Perhaps, the scientists wrote in the journal Science, "the mind may wander simply because it can."

- Top Ten Unexplained Phenomena

- World Trivia: Challenge Your Brain

- Do People Really Use Just 10 Percent of Their Brains?

- Animals Dream in Pictures, Too

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus