'Bomb Carbon' from Cold War Nuclear Tests Found in the Ocean's Deepest Trenches

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

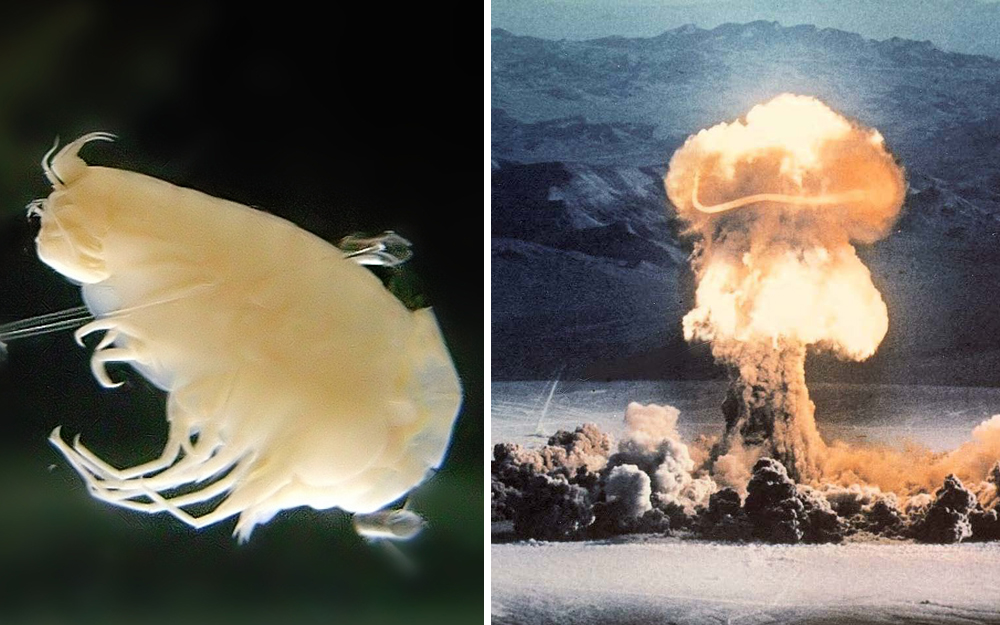

Crustaceans that live in the deepest part of the ocean carry radioactive carbon in their bodies, a legacy of nuclear tests performed during the Cold War.

Researchers recently found elevated levels of radiocarbon in amphipods — shell-less, shrimp-like creatures — from deep trenches in the western Pacific Ocean, up to 7 miles (11 kilometers) below the surface.

In those dark and high-pressure depths, deep-sea amphipods scavenge decaying organic matter that drifts down from above. By eating the remains of animals that were exposed to radioactive fallout from Cold War nuclear tests, the amphipods' bodies have also become infused with radiocarbon — the isotope carbon-14, or "bomb carbon" — the first evidence of elevated radiocarbon at the sea bottom, scientists wrote in a new study. [In Photos: The Wonders of the Deep Sea]

When global superpowers detonated nuclear bombs in the 1950s and 1960s, the explosions spewed neutrons into the atmosphere. There, the neutral particles reacted with nitrogen and carbon to form carbon-14, which re-entered the ocean to be absorbed by marine life, according to the study.

Some carbon-14 occurs naturally in the atmosphere and in living organisms. But by the mid-1960s, atmospheric radiocarbon levels were roughly twice what they were before nuclear testing began, and those levels didn't start to drop until testing ceased, the researchers reported.

Soon after the first nuclear explosions, elevated quantities of carbon-14 were already appearing in ocean animals near the sea surface. For the new study, researchers went deeper, examining amphipods collected from three locations on the sea bottom in the tropical western Pacific: the Mariana, Mussau and New Britain Trenches.

Bottom feeders

Organic matter in the amphipods' guts held carbon-14, but the carbon-14 levels in the amphipods' bodies were much higher. Over time, a diet rich in carbon-14 likely flooded the amphipods' tissues with bomb carbon, the scientists concluded.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They also found that deep-sea amphipods were bigger and longer-lived than their cousins closer to the surface. Amphipods in the ocean trenches lived to be more than 10 years old, and measured nearly 4 inches (10 centimeters) long. By comparison, surface amphipods live to be less than 2 years old and grow to be only 0.8 inches (2 cm) in length.

The deep-sea amphipods' low metabolic rate and longevity provide fertile ground for carbon-14 to accumulate in their bodies over time, according to the study.

Ocean circulation alone would take centuries to carry bomb carbon to the deep sea. But thanks to the ocean food chain, bomb carbon arrived at the seafloor far sooner than expected, lead study author Ning Wang, a geochemist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Guangzhou, said in a statement.

The study underscores how humans' impact on ocean ecosystems near the surface can circulate through miles of water, affecting creatures in its deepest depths.

"There's a very strong interaction between the surface and the bottom, in terms of biologic systems," study co-author Weidong Sun, a geochemist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Qingdao, said in the statement.

"Human activities can affect the biosystems even down to 11,000 meters [36,000 feet], so we need to be careful about our future behaviors," Sun said.

Indeed, recent studies have also shown evidence of plastic in the guts of marine animals inhabiting deep-sea trenches.

The findings were published online April 8 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

- Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench

- In Photos: James Cameron's Epic Dive to Challenger Deep

- In Photos: Spooky Deep-Sea Creatures

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus