Dead Planet's Heavy Metal Core Found Rocketing Around a Dead Sun in a Distant Solar System

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

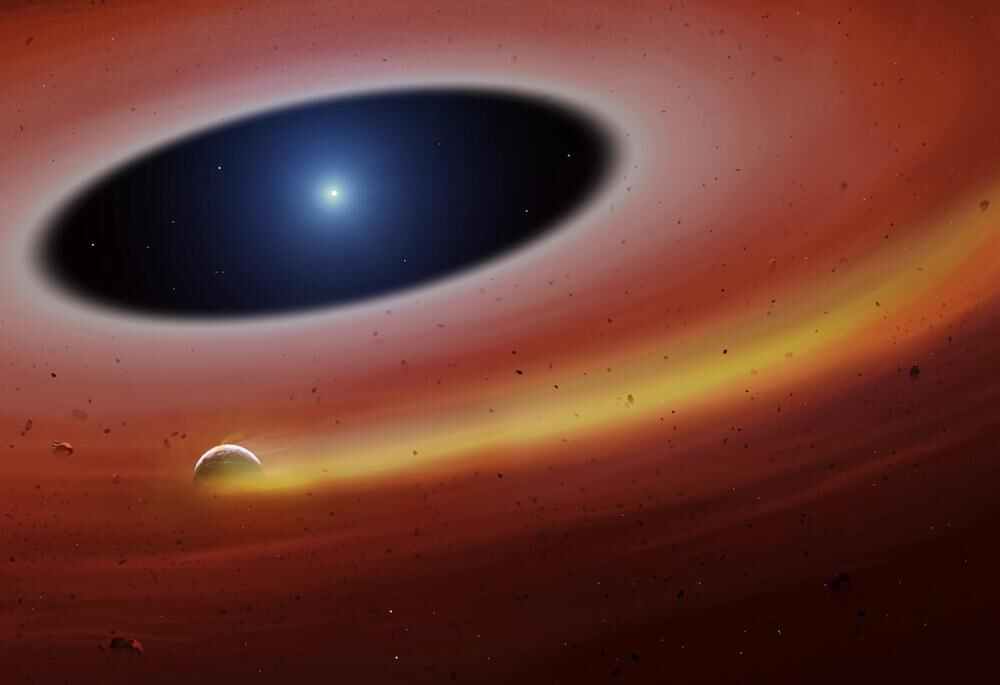

In case you forgot that nature is totally metal, astronomers have discovered the shattered remains of a dead planet orbiting a dead sun in a distant, desolate solar system.

The dead planet's broken heart consists of heavy metal, and it orbits at breakneck speed through a dirty cosmic boneyard full of other chunks of dead planets. Mourn the dead planet and its dead star if you like, but do not pity them; one day, astronomers say, our solar system will probably look much the same. (Happy spring!)

This grim conclusion, which is described today (April 4) in the journal Science, comes from observing a dead planet chunk (or "planetesimal") circling a white dwarf star in a solar system about 410 million light-years away from Earth. [9 Times Nature Was Totally Metal]

The violent death of a sun

Like all white dwarfs — which form after stars like Earth's sun run out of fuel, balloon outward in fiery cataclysms, then shrivel down into dead crystalline husks — the star that caught the team's attention is extremely dense. According to the researchers, this white dwarf packs about 70 percent of the mass of our sun into a tiny sphere no larger than Earth, giving it a devastating gravitational pull.

"The white dwarf's gravity is so strong — about 100,000 times that of the Earth — that a typical asteroid will be ripped apart by gravitational forces if it passes too close," lead study author Christopher Manser, a physicist at the University of Warwick in Coventry, England, said in a statement.

Indeed, Manser and his colleagues saw that a hodgepodge halo of pulverized rocks swirled around the white dwarf's perimeter. A spectroscopic analysis of the light emitted by the star and its halo showed that the disk was full of heavy elements like iron, magnesium and oxygen — key ingredients in making rocky planets like Earth.

No rest for the dead

This gave the researchers some clues about one object, in particular, that seemed to be swirling through the halo faster than the rest. The mysterious object was moving so fast that it completed a full orbit of its dead star once every 2 hours, the researchers wrote, leaving a comet-like tail of gas streaking behind it.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To orbit so quickly, the object clearly had to be very close to the white dwarf — closer than seemed possible given the dead star's intense gravitational pull. For this to be the case, the object "must be very dense or very likely to have internal strength that holds it together," study co-author Boris Gaensicke, a professor of physics at the University of Warwick, said.

The team concluded that to hold its form so deeply within the white dwarf's well of gravity, the mystery object must consist largely of the heavy metals like iron and nickel. And it was most likely the sturdy core of a planet that survived its star's cataclysmic death, the researchers found. The original planet would have been at least hundreds of miles in diameter, the researchers wrote, but may now be reduced to a lump of core as small as 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) wide.

A glimpse of Earth's future

That any piece of a planet, however small, could survive so close to a white dwarf is remarkable, the researchers wrote. Learning more about this dusty, dead solar system might even yield some surprises and insights about the ultimate fate of our system.

"The general consensus is that 5 [billion to] 6 billion years from now, our solar system will be a white dwarf in place of the sun, orbited by Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the outer planets, as well as asteroids and comets," Manser said.

As for Earth and its smaller neighbors? The sun will probably engulf them as it balloons into a red giant, burning through the last of its fuel and seizing back the precious gift of life that it once gave. Perhaps then, future alien astronomers will look upon the graveyard of our solar system — and just maybe, if they see the resilient heart of a once-thriving planet clattering through the debris, they, too, will think, "That's metal."

- 15 Unforgettable Images of Stars

- 9 Strange, Scientific Excuses for Why Humans Haven't Found Aliens Yet

- The 12 Strangest Objects in the Universe

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus