Brain of Mysterious 'Little Foot' Human Relative Was Half-Man, Half-Ape

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The brain of one of the oldest Australopithecus individuals ever found was a little bit ape-like and a little bit human.

In a new study, researchers scanned the interior of a very rare, nearly complete skull of this ancient hominin ancestor. Hominins include modern and extinct humans and all their direct ancestors, including Australopithecus, which lived between about 4 million and 2 million years ago in Africa, and early humans of the genus Homo would eventually evolve from Australopithecus ancestors.

The modern human brain owes a lot to these small, hairy human ancestors, but we know very little about their brains, said Amélie Beaudet, a paleontologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa. [In Photos: 'Little Foot' Human Ancestor Walked with Lucy]

Between ape and human

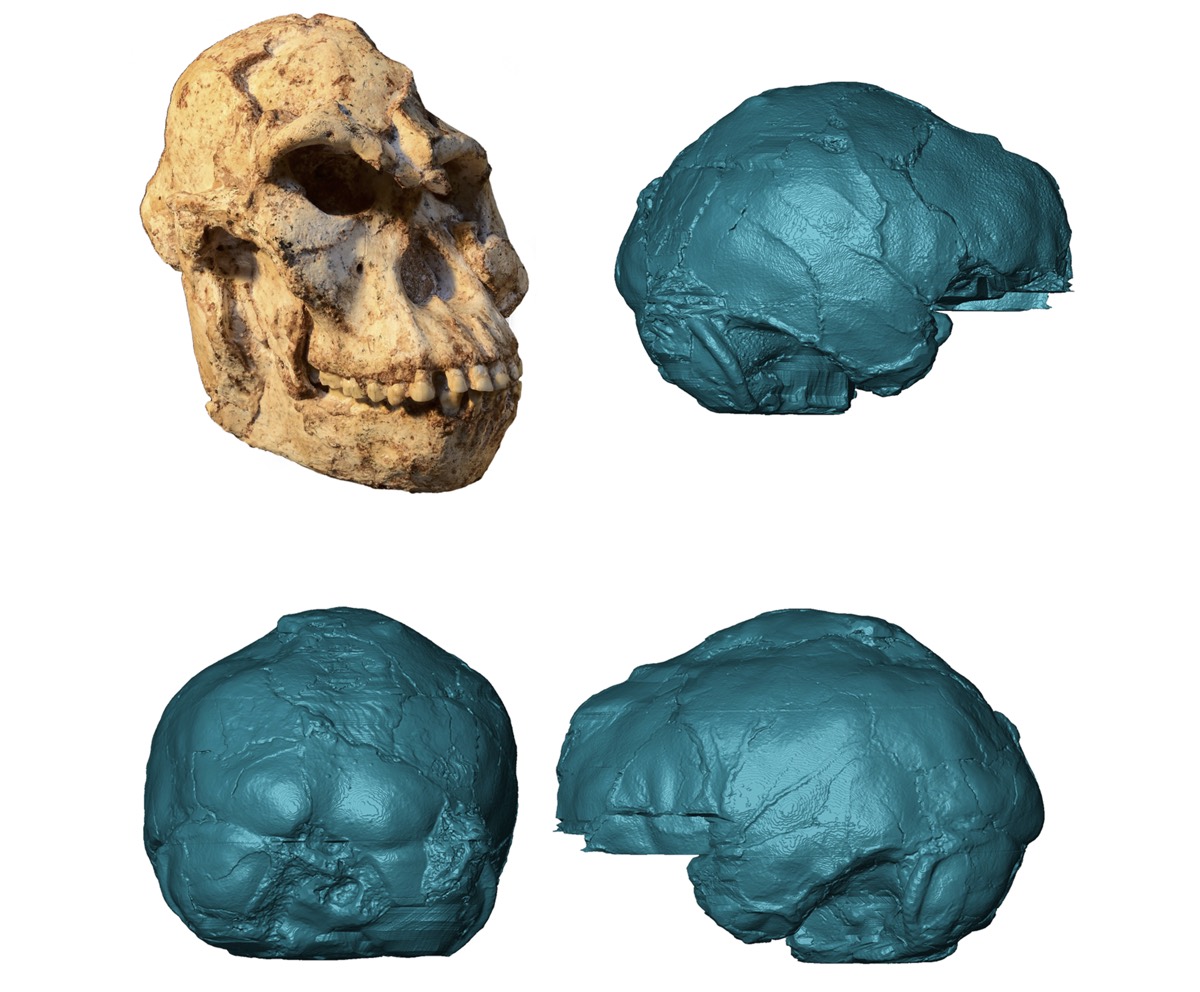

Beaudet and her colleagues used micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), a very sensitive version of the same sort of technology a surgeon might use to scan a bum knee. With this tool,the researchers reconstructed the interior of the skull of a very old Australopithecus.

The skull belongs to a fossil dubbed "Little Foot," first found two decades ago in Sterkfontein Caves near Johannesburg. At 3.67 million years old, Little Foot is among the oldest of any Australopithecus ever found, and its skull is nearly intact. The fossil's discoverers think it may belong to an entirely new Australopithecus species, Live Science reported.

With micro-CT, the research team could see very fine imprints of where the brain once lay against Little Foot's skull, including a record of the paths of veins and arteries, Beaudet told Live Science. Using the skull to infer brain shape in this way is called making an endocast.

"I was expecting something quite similar to the other endocasts we knew from Australopithecus, but Little Foot turned out to be a bit different, in accordance with its great age," Beaudet said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Today's chimpanzees and humans share an ancestor older than Little Foot: some long-lost ape that gave rise to both lineages. Little Foot's brain looks a lot like that predicted ancestor's should look, Beaudet said, more ape-like than human. Little Foot's visual cortex, in particular, took up a greater proportion of its brain than that area does in the human brain.

In humans, Beaudet said, the visual cortex has been pushed aside to accommodate the expansion of the parietal cortex, an area involved in complex activities like toolmaking.

Changing brains

Little Foot's brain was asymmetrical, with slightly differing protrusions on each side, the researchers found. This is a feature shared with both humans and apes, and it probably indicates that Australopithecus had brain lateralization, meaning that the two sides of its brain performed different functions. The finding means that brain lateralization evolved very early in the primate lineage. [Homo Naledi in Photos: Images of the Small-Brained Human Relative]

Little Foot's brain was different from later Australopithecus specimens, Beaudet said. The visual cortex, in particular, was larger compared to later Australopithecus brains. These differences hint that brain evolution was a piecemeal process, occurring in fits and starts across the brain. .

The findings will appear in a special issue on Little Foot being published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

- Photos: Earliest Known Human Fossils Discovered

- Photos: Looking for Extinct Humans in Ancient Cave Mud

- In Photos: Uncovering a New Human Species

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus