Trilobite Tummies Revealed in New Fossils

Trilobite tummies were more complex than previously believed, new fossils reveal.

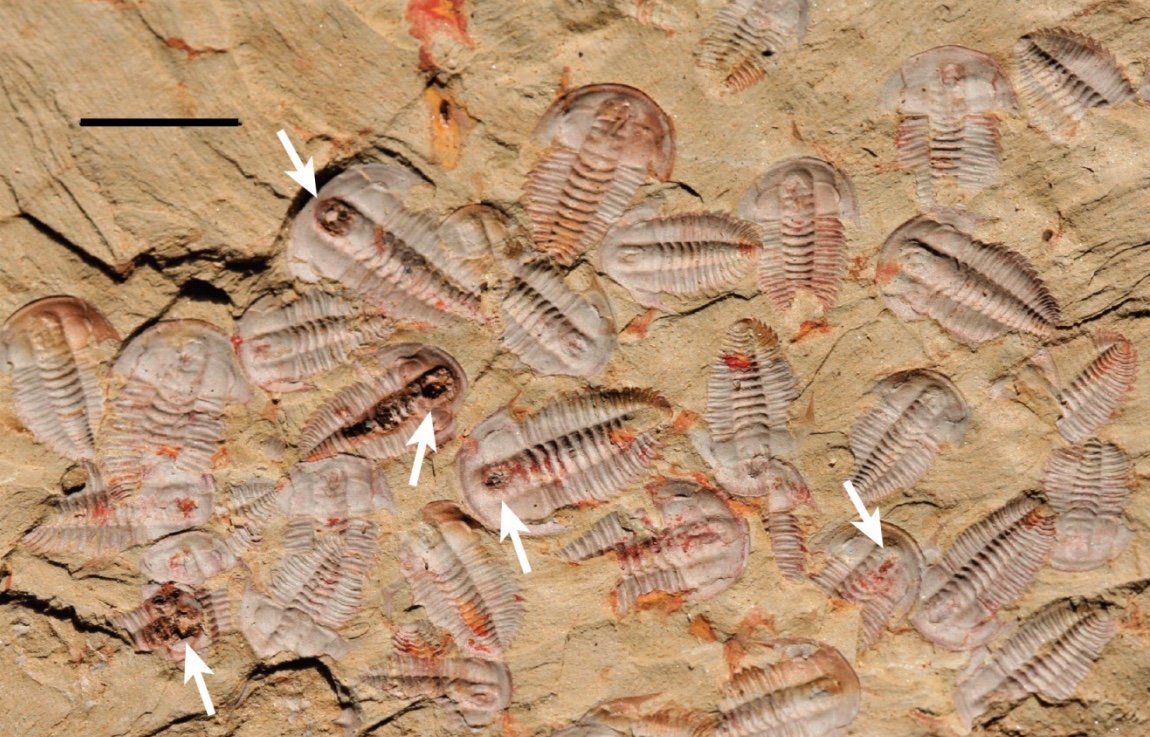

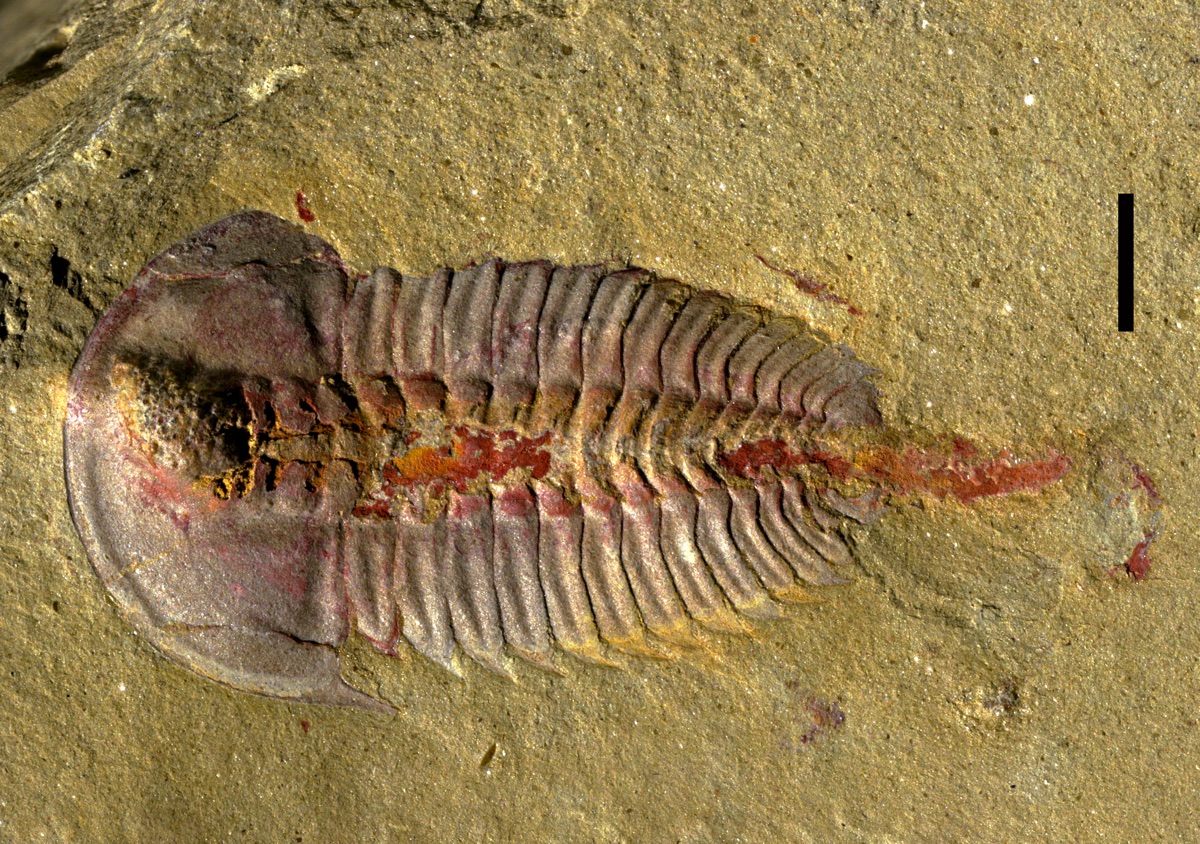

The fossils, which hail from China, preserve the guts of trilobites in long, iron-rich strips. Trilobite fossils are a dime a dozen — sort of like cockroaches of the sea in that respect. They were abundant for nearly 300 million years before they went extinct about 252 million years ago — but trilobite fossils that reveal internal organs are rare, according to a new study on the fossils published Sept. 21 in the journal PLOS ONE.

The fossils show that early trilobites had crops, or stomach-like pouches that were once thought to have evolved only later in the trilobite lineage. One trilobite species even boasted a crop along with more simplified digestive glands, suggesting that the evolution of the trilobite digestive system was complicated, the researchers found. [Video: Primitive Sea Creatures Called Trilobites Were Advanced Ninja Attackers]

Complicated guts

Until now, researchers thought that there were two types of trilobites: those with crops and those without. The second type had a long tube from the mouth to the anus that was lined with digestive glands that would have squirted juices to help digestion. In contrast, those with crops had a stomach-like pouch where food would break down, but they had no additional digestive glands.

There was one specimen, analyzed in 2012, that seemed to have both, but that was a juvenile, so researchers weren't sure whether the digestive system was the same as what would have been seen in an adult of the same species. Otherwise, most species with crops were from younger rock than species with gut tubes, so trilobite researchers thought that perhaps crops were a late evolutionary addition.

The new research suggests otherwise. Using fossils found in a rock layer called the Guanshan biota of southern China, researchers from the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York, Northwest University in Xi'an, China, and the Chengdu Institute of Geology and Mineral Resources found crops in the trilobite species Redilchia mansuyi and Palaeolenus lantenoisi. P. lantenoisi had both a crop and digestive glands, they reported.

The trilobite diet

These crop-bearing fossils date back 514 million years, to the beginning of the Cambrian period.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is a very rigorous study based on multiple specimens, and it shows that we should start thinking about this aspect of trilobite biology and evolution in a different way,” study leader Melanie Hopkins of the AMNH said in a statement.

Trilobites were thought to vacuum their way along the ocean floor, scooping up sediment and organic material, and digesting the latter while excreting the former. But the new study found little evidence of sand-and-soil elements like aluminum, silicon and magnesium in trilobite guts. Some species may have been savvy hunters, grabbing marine worms and wrestling them into submission with their many legs.

Editor's Note: This article was updated to fix two statements about the trilobite finding.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus