Trilobites Were Stone-Cold Killers

Trilobites were savvy killers who hunted down their prey and used their many legs to wrestle them into submission, newly discovered fossils suggest.

The fossils come from a site in southeastern Missouri, not far from the city of Desloge. They are trace fossils, which means they preserve not the organisms themselves, but their burrows. The burrows were made by various species of trilobite as well as by unknown, wormlike creatures.

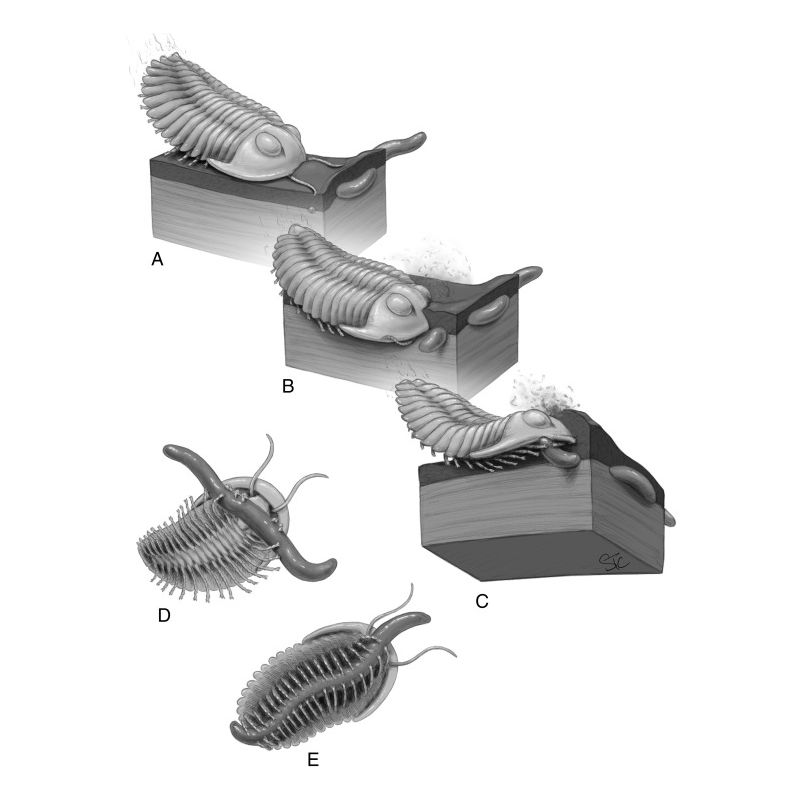

A statistical analysis of these burrows and their intersections shows that they cross one another more than expected, a sign that the trilobites were deliberately hunting down their wormy prey. In a subset of those cases, the trilobites seemed to sidle up to the burrows in parallel, perhaps so they could latch onto the worms lengthwise with their row of legs. [Video: Primitive Sea Creatures Were Advanced Ninja Attackers]

"This is legitimately the moment of interaction between the trilobite and the animal that it ate," said study researcher James Schiffbauer, a paleobiologist at the University of Missouri.

Trilobite tracks

The discovery of these fossils came about by accident. During a department field trip to visit a local lead mine, the researchers made a side trip to a known fossil spot. While there, study co-author John Huntley, also a professor at the University of Missouri, stumbled across a block of fossilized burrows, frozen in silty shale. The sediment was set down during the Cambrian period, between 540 million and 485 million years ago, when the area was a shallow nearshore environment. The shallow bottom was likely covered with a dense microbial mat, which made for a rich food source for wormy (or "vermiform") creatures. These worms were, in turn, prey for trilobites.

"It became sort of a small shallow-water hunting ground for the trilobites," Schiffbauer told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Graduate student Tara Selly took on the painstaking task of cataloguing and counting the burrows and their intersections. Her findings revealed that the worm and trilobite tunnels intersected about 30 percent of the time — more than would be expected based on chance alone.

"Likely one-third of [the burrows] were actually capturing predatory events," Selly told Live Science.

A moment in time

The trilobites known from this area belong to species with particularly large eyes, Schiffbauer said. Those eyes may have made them adept hunters, he said, able to seek out burrow entrances or impressions. The critters would then burrow down to grasp their prey.

"What we're seeing is really sophisticated behavior fairly early on in what some people would say is a very simple creature," Schiffbauer said. The trilobites might also have used scent to sniff out their prey, he said.

Predation is important to understand, Huntley told Live Science, but it can be hard to see in the fossil record. Some Cambrian fossils have recorded animals inside the gut tracts of other animals, but it's not clear whether they were hunted and eaten or scavenged. Other signs of predation in the fossil record are wounds or drill holes in skeletons or shells, Huntley said.

"In this case, what we're getting is actually impressions of the body," Huntley said. "It's a different window into this process that we know is important ecologically and really important evolutionarily as well."

The research iss detailed online in the Feb. 15 issue of the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.