Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

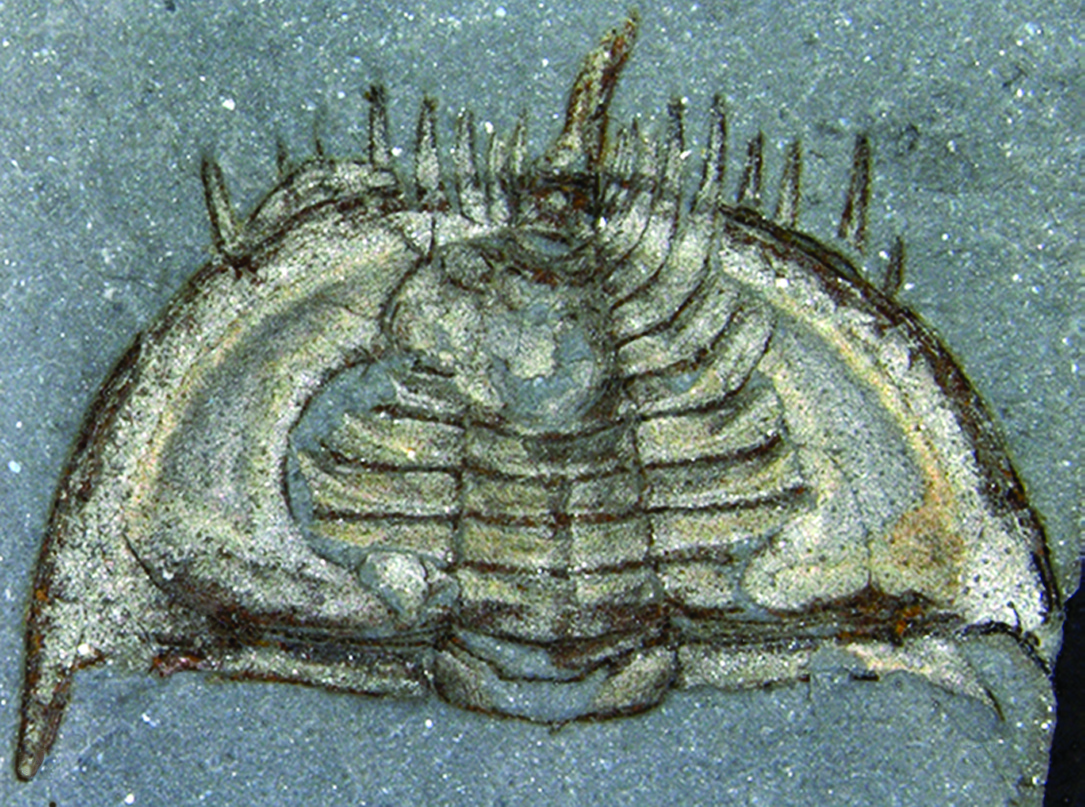

About 513 million years ago, a creature curled up like a pill bug to protect itself from predators, a recently-discovered fossil suggests.

The new discovery is the oldest evidence that trilobites rolled up in self-defense so early in their evolutionary history.

"Until now, it was thought that this group was incapable of enrolling, as they lack various of the complex adaptations observed in younger trilobites," study co-author Javier Ortega-Hernández, a paleobiologist at the University of Cambridge in England, wrote in an email.

Iconic creatures

Trilobites are some of the most common, and iconic, creatures that emerged during the Cambrian Period, when the diversity of life on the planet exploded. These extinct creatures, which are related to spiders and crustaceans, died off more than 250 million years ago. [Cambrian Creatures: Images of Primitive Sea Life]

Younger examples of trilobites were known to roll up like roly-polies to avoid predators. But until now, evidence that older trilobites did the same thing was scarce.

Ortega-Hernández and his colleagues were studying a collection of hundreds of trilobite fossils that were excavated from Jasper National Park in Canada. He immediately noticed that one ancient trilobite, which belonged to a group called olenellids, seemed to have spines in front of its head.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Looking under a microscope, he realized the trilobite had actually curled its tail under its head.

By comparing the prickly creatures with later relatives that also rolled up, Ortega-Hernández concluded that the trilobite was doing the same thing.

"It turned out that this case was millions of years older than the previously known oldest occurrence, and thus became very significant for understanding the origin of this complex strategy in trilobites," he said.

Trilobites typically flexed their tails under their heads, and the spines on their tails provided a kind of armor in front of their heads that helped to ward off predators.

Because the creature's exoskeleton was well preserved and undistorted — showing a similar body posture to that of other trilobites that curled up — it's unlikely the fossil got that way due to "serendipitous squashing," Ortega-Hernández said.

Even so, the researchers are unlikely to find another rolled-up trilobite from this period due to the organism's body plan, they said.

"Because these early trilobites did not have complex locking devices that would keep the enrolled configuration even after death, the best possibility of preserving this behavior was for an enrolled trilobite to be buried rapidly by sediment," Ortega-Hernández said. "This also explains, in part, why enrollment had not been recognized for the group earlier, as the conditions required for preserving these fossils were exceptional."

The findings were detailed today (Sept. 24) in the journal Biology Letters.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus