Chambers Hidden in Great Pyramid? Scientists Cast Doubt

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A group of scientists has just claimed to have discovered two unknown voids or cavities within the Great Pyramid of Giza, the largest pyramid ever constructed in Egypt.

Such cavities can be signs of hidden burials or rooms and as such, media outlets across the world immediately ran headlines touting this "discovery." One outlet even went so far as to proclaim that "secret rooms" had been found in the Great Pyramid.

However, Live Science has learned that the results are more ambiguous. Scientists who are charged with overseeing the team's work, including Zahi Hawass, Egypt's antiquities minister, said they are not convinced that sizable voids or cavities have been discovered. [See Images of the Great Pyramid and the 'Voids']

Built by the Pharaoh Khufu over 4,500 years ago, the Great Pyramid is the largest such structure in Egypt, and one of three pyramids built at Giza. It rose 481 feet (146 meters) tall when it was first built, although the loss of stone due to weathering and quarrying of the pyramid means that the structure rises only about 455 feet (138 m) today. Ancient writers called the pyramid a "wonder of the world." It was the tallest building in the world until the Lincoln Cathedral was completed in England in the 14th century.

Unknown voids?

On Saturday (Oct. 15), the Scan Pyramids Project issued a press release saying that two previously unknown voids or cavities had been discovered in the Great Pyramid of Giza. The project consists of a group of scientists from different universities, institutes and companies who are scanning Egypt's pyramids using various technologies.

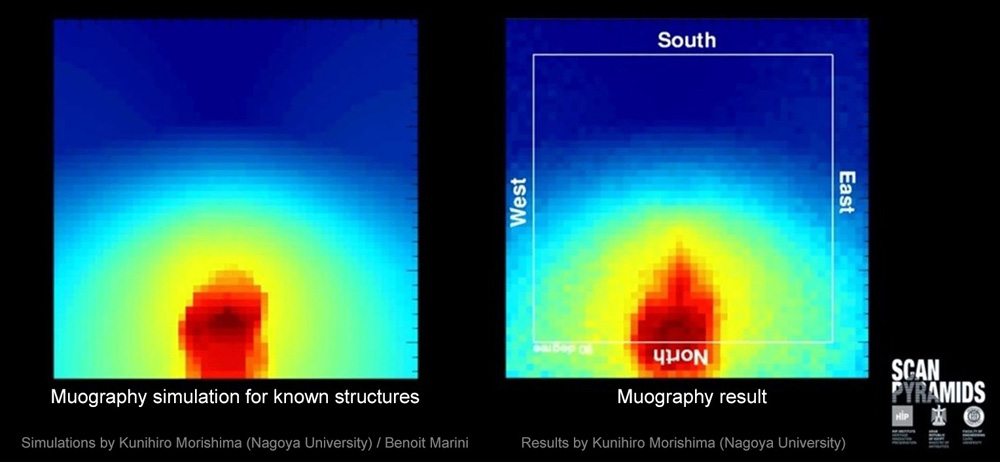

To find the voids, scientists used muography, a technique that measures the density of muons, or subatomic particles that are the primary component of cosmic rays raining down on Earth. [In Photos: Inside Egypt's Great Pyramids]

"Muon particles permanently reach the Earth with a speed close to the speed of light and a flux around 10,000 per m² per minute. They originate from the interactions of cosmic rays created in the universe with the atoms of the upper atmosphere," said the Scan Pyramids project team in its press release. The researchers added that these particles can "go through hundreds of meters of stone before being absorbed."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Muons can easily cross areas where there are voids or cavities, but the particles are sometimes absorbed or deflected when they hit denser material, the team said. By measuring changes in muon particles as they go deeper into the pyramid the team can search for hidden areas. "The challenge of such measurements consists in building extremely precise detectors and in accumulating enough data — over several days or months — to increase the contrast," the team said in the statement.

Caution urged

However, a team of scientists appointed by the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities to oversee the work of the Scan Pyramids Project team said it is not convinced that sizable voids or cavities have been discovered. This oversight team is led by former antiquities minister Zahi Hawass and includes several Egyptologists with decades of experience. Mark Lehner, who has been conducting work at Giza for about 30 years, is one of the team members.

That group issued its own press release, through the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, saying that more work needs to be done. The researchers recommended extending the Scan Pyramids project by another year so that more data can be gathered. They used the term "anomalies" in the press release rather than calling the findings "voids" or "cavities."

Hawass told Live Science that the results obtained by the Scan Pyramid team may be the result of different-size stones used in the Great Pyramid and may not indicate the presence of sizable voids.

"The core [of the pyramid] has big and small stones, and this can show hollows everywhere," he said. The oversight team "asked for more work to know the size and the function" of the anomalies, Hawass said.

Hard lessons learned

Egypt’s antiquities ministry decided to have a group of experienced Egyptologists oversee scanning work after a debacle that occurred at Tutankhamun's tomb. In an incident that started last year, an Egyptologist named Nicholas Reeves claimed to have found evidence that the tomb of Queen Nefertiti was hidden behind a secret doorway in King Tut's tomb.

An initial scan suggested that such a tomb may exist, creating a media stir, though provoking skeptical reactions from scientists not involved with Reeves' work. More-detailed scans carried out earlier this year revealed that there was no such Nefertiti tomb.

Before the negative results from the second series of scans came back, officials in the Egyptian antiquities ministry, as well as the tourism ministry, had publicly stated that they believed a hidden chamber, possibly containing Nefertiti's tomb, likely existed. After the negative results, and critical views of the first scan from outside scientists, the antiquities ministry had to backpedal from that position.

Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus