Photos: Oddball Bees Build Nests Out of Sandstone

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Anthophora Pueblo

A new species of desert-dwelling bee, Anthophora pueblo, peeks out of its sandstone nest. These bees gnaw holes into the rock, a difficult process that leaves older bees with worn-out mandibles. New research published Sept. 12 in the journal Current Biology, however, suggests that these bees get benefits from building their homes to last.

[Read full story on the sandstone bees]

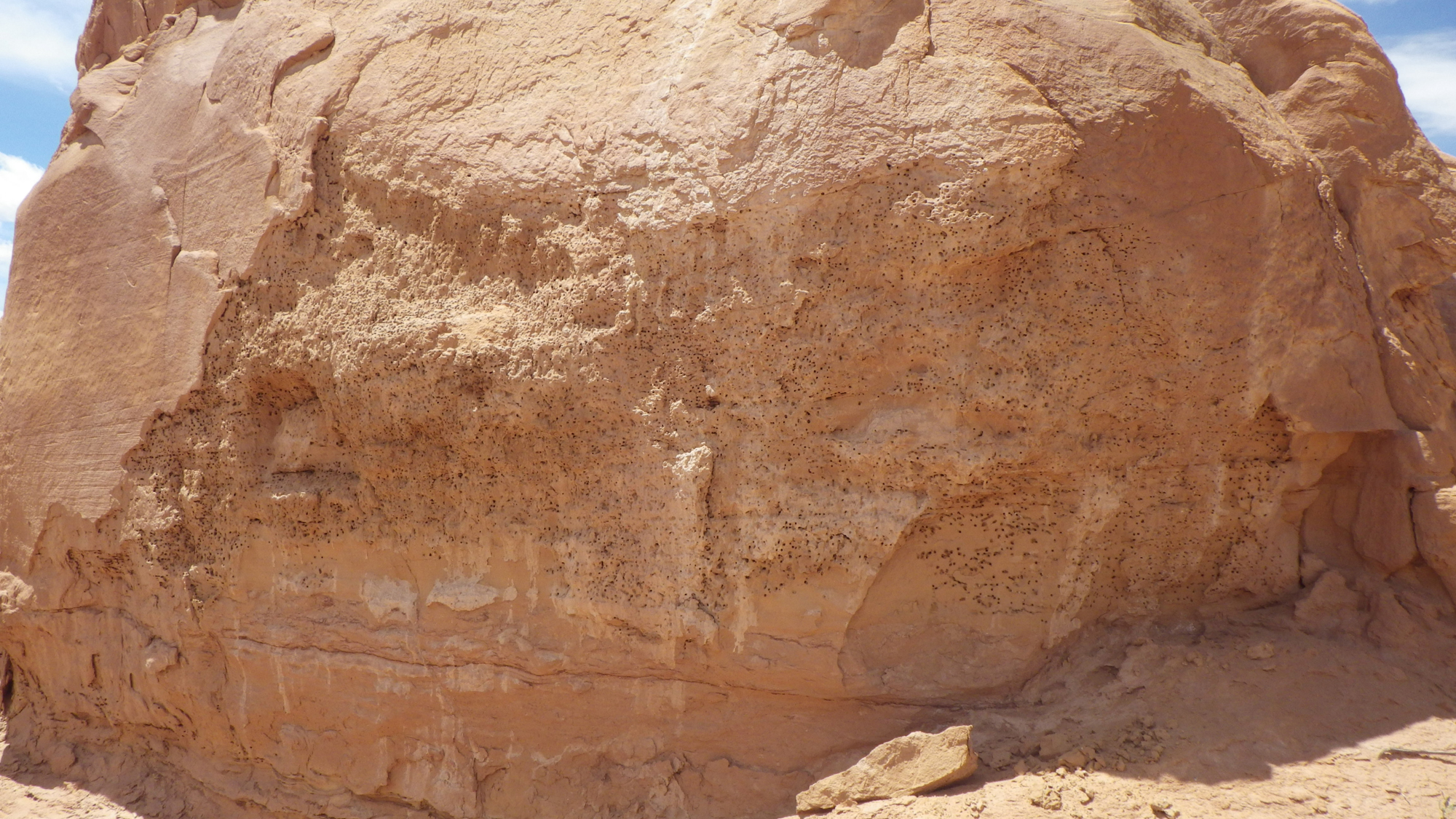

A Bee Pueblo

Anthophora pueblo nests at Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah. Bees reuse the tunnels for generations, meaning that the hard work of excavation may pay off for a bee's offspring.

Bunches of bees

A sandstone wall is crammed with Anthophora pueblo bee nests at Johnson Lakes Canyon in Utah. Researchers reported seven sites in Utah, Colorado and California where these bees nest in a Sept. 12 paper in the journal Current biology. Since then, study author Michael Orr of Utah State University says he's found more than 50 additional nesting sites. The bees require habitat with just the right hardness of sandstone — not too hard — Orr told Live Science, and they need a water source nearby.

[Read full story on the sandstone bees]

Hunting for bees

Michael Orr, a doctoral student at Utah State University, climbs a rock wall in southern Utah to hunt for sandstone-dwelling bees. Orr and his colleagues have found that digging into rock walls seems to benefit bees because their nests are durable. When times are lean, the bees delay their emergence and can remain holed up in a quiescent state for at least four years. Nesting in rock walls helps ensure that the bees are protected from erosion or flash flood during these periods.

A Home for Bees

A large bee nesting site near Wild Horse Creek in south-central Utah. Researchers found fewer microbes in vertical sandstone rock than sandstone on the ground. They also found that parasitic beetles that prey on bees aren't able to develop as effectively inside sandstone nests. The sandstone dwellings may thus protect bees from parasites both large and small.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Wild Horse Creek

And the views aren't bad, either! A large sandstone formation provides a home for Anthophora pueblo bees near Wild Horse Creek in south-central Utah. The bee tunnels become shelter for other insects, too, including several species of parasites, other bee species, wasps and spiders.

[Read full story on the sandstone bees]

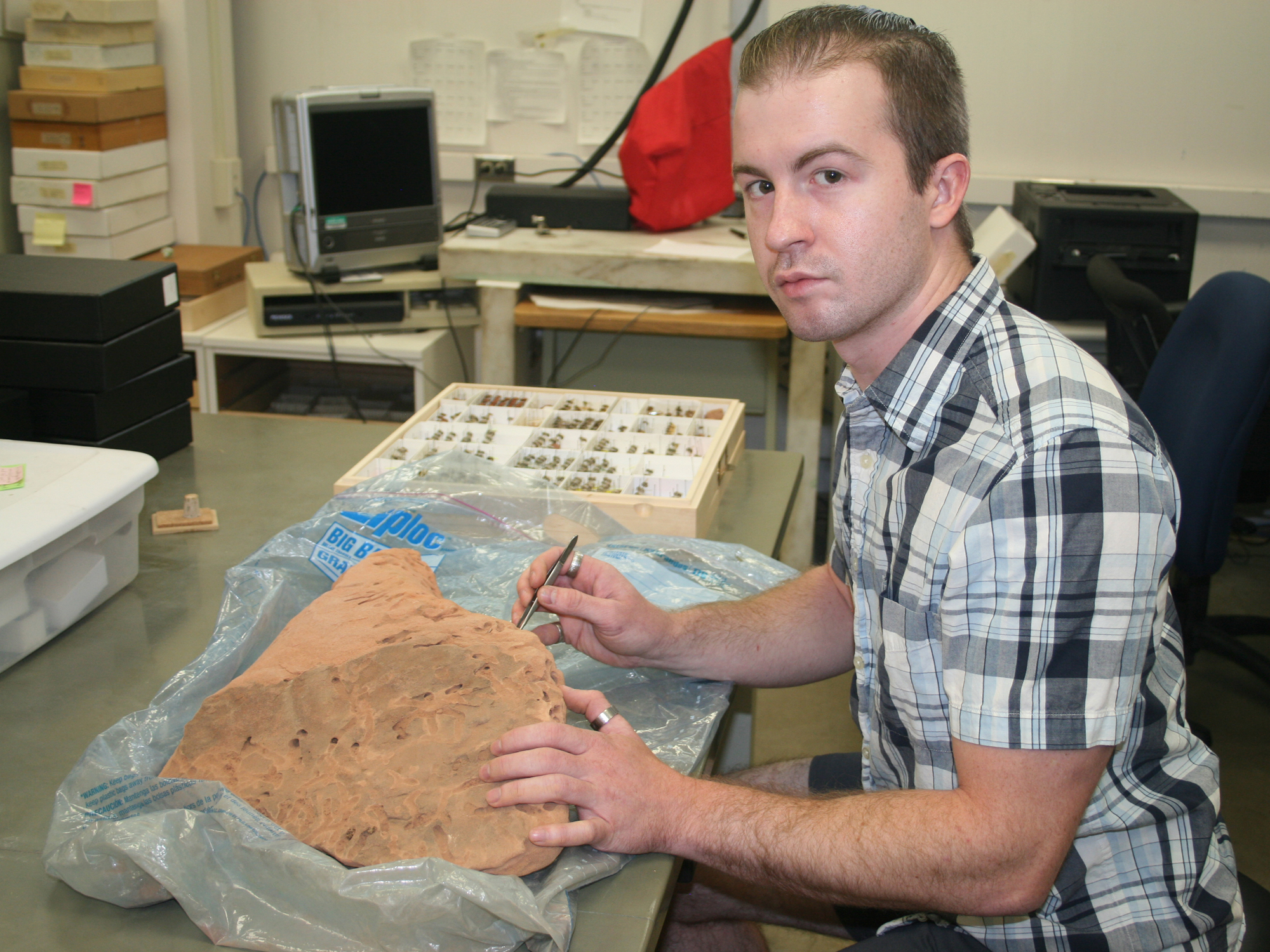

Studying sandstone

Michael Orr of Utah State University with a chunk of sandstone removed from the San Rafael desert of Utah in the early 1980s. U.S. Department of Agriculture entomologist Frank Parker was the first to notice bees building nests in sandstone. He chiseled out rock samples and reared the bees in the lab, but never formally identified the species or published his research.

Anthophora pueblo specimen

Utah State University doctoral student Michael Orr displays a specimen of Anthophora pueblo along with its sandstone nest. Samples of this new species had been tucked away in a museum drawer for nearly 40 years before researchers formally identified the new bee.

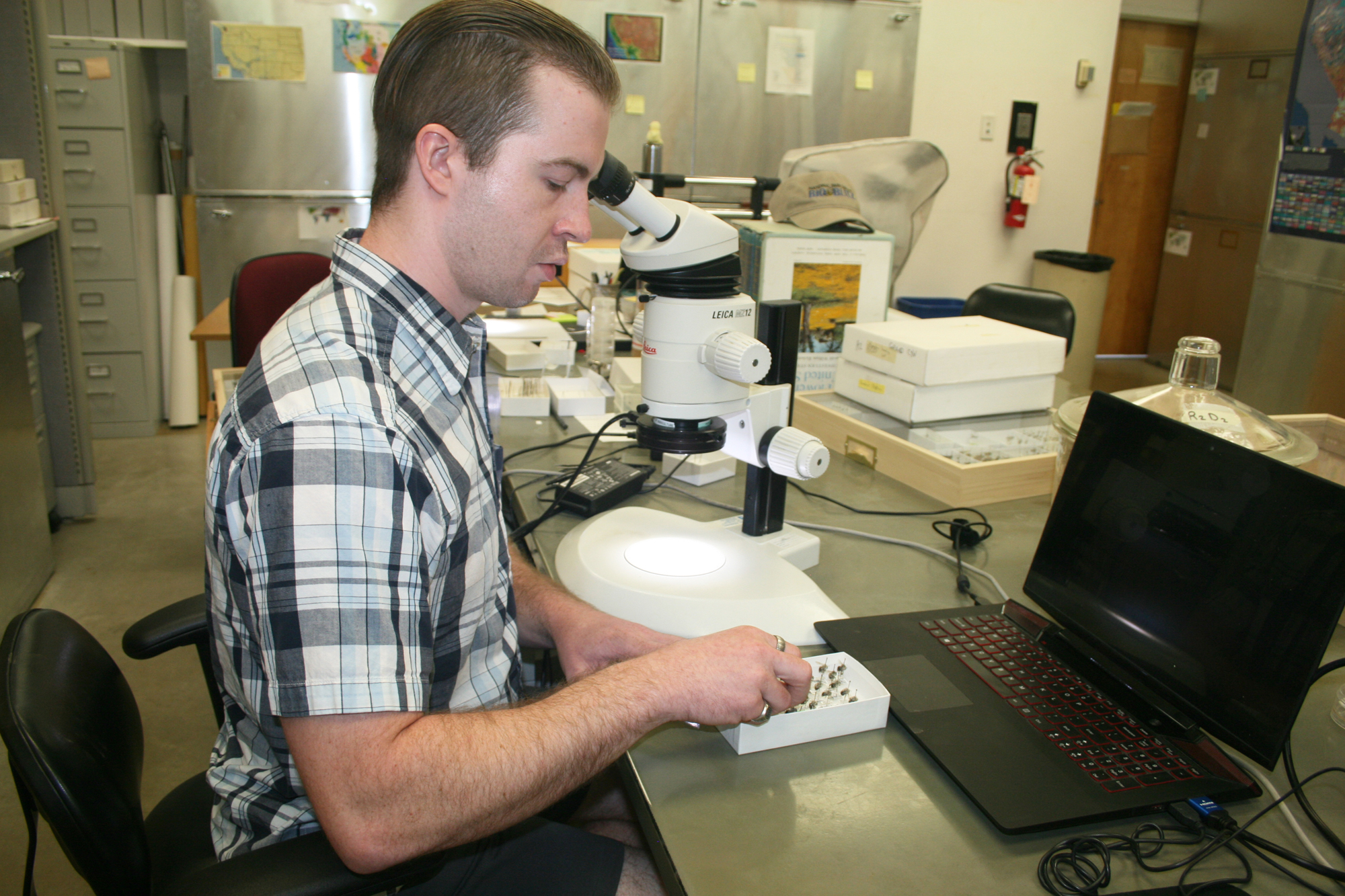

Identifying a new species

Michael Orr of Utah State University selects a specimen of Anthophora pueblo for examination under a microscope. The desert bee seems to gain protection from the elements and from parasites by gnawing its nests out of solid rock.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus