X-Ray Laser Vaporizes Water Droplets in Striking New Video

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have captured dramatic video footage of what happens to liquid droplets when they are hit with the beam of an X-ray laser. Spoiler alert: They explode.

These are the first movies of the microscopic realm showing water being vaporized by the world's brightest X-ray laser, taken at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Data from this research could lead to better understanding and use of X-ray lasers in experiments, according to SLAC.

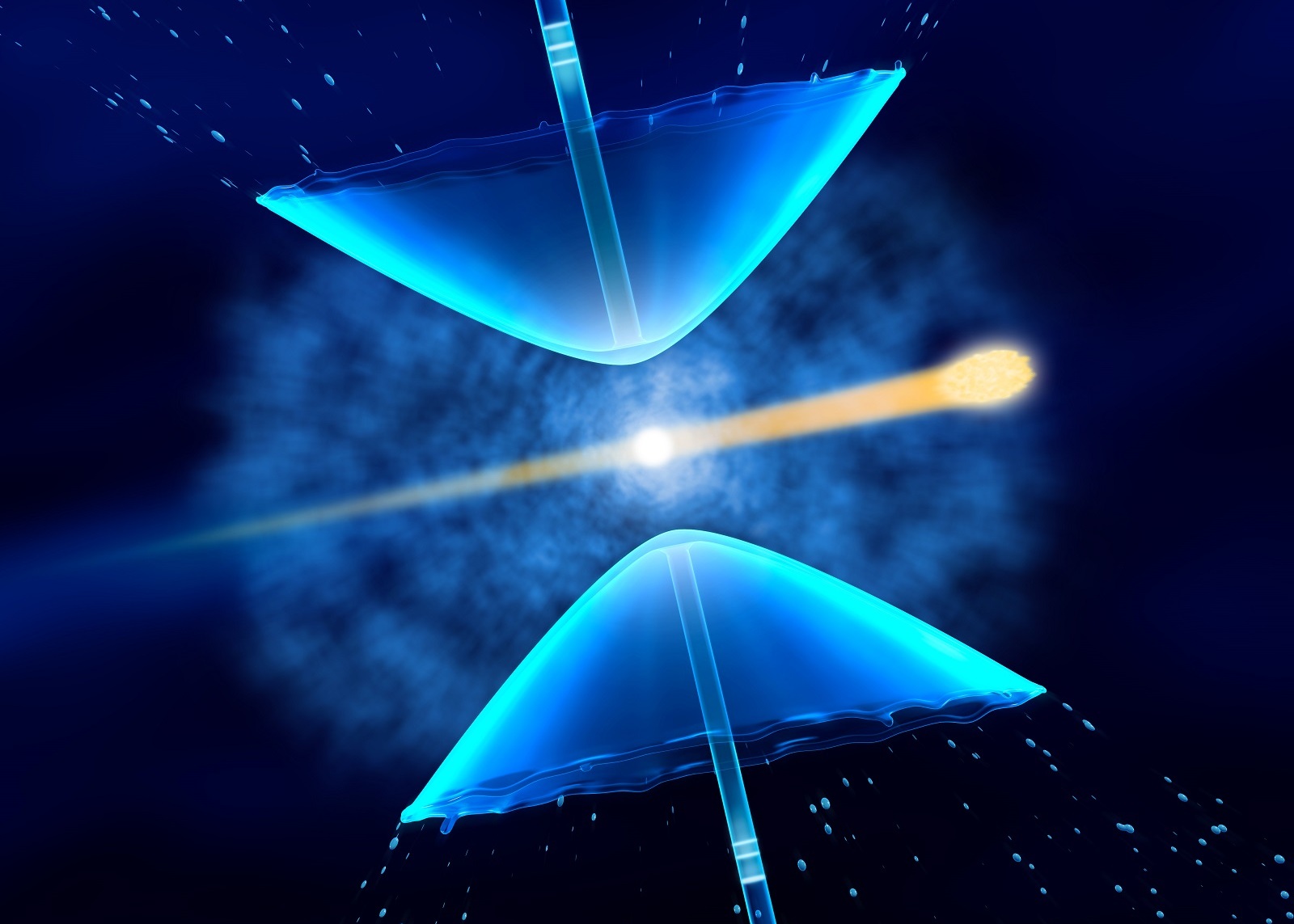

The footage shows the X-ray pulse ripping a drop of liquid apart, which creates a cloud of smaller particles and vapor. When the X-ray pulse hits a jet of liquid,it initially creates a hole in the stream. As the gap grows, the ends of the jet become an umbrella-like shape, eventually folding back to merge with the jet. [Gallery: Dreamy Images Reveal Beauty in Physics]

Scientists use X-ray lasers' extremely bright, fast flashes of light to take atomic-level snapshots of nature's speediest processes.

"Understanding the dynamics of these explosions will allow us to avoid their unwanted effects on samples," Claudiu Stan of the Stanford PULSE Institute, a joint institute of Stanford University in California and SLAC, said in a statement.

"It could also help us find new ways of using explosions caused by X-rays to trigger changes in samples and study matter under extreme conditions," he said. "These studies could help us better understand a wide range of phenomena in X-ray science and other applications."

Liquids are commonly used to bring samples into the X-ray beam's path for analysis. In only a tiny fraction of a second, samples can blow up from the power of an ultrabright X-ray, but researchers can, in most cases, take the data they need before damage sets in.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new study, published online May 23, 2016, in the journal Nature Physics, shows, in microscopic detail, how these explosions unfold. The researchers took one image, timed from five-billionths of a second to one ten-thousandth of a second, for each X-ray pulse hitting the liquid. The images were then edited together into movies.

From the data gathered during these experiments and their resulting movies, the researchers developed mathematical models to describe the liquid explosions. These models could help researchers tune the lasers more precisely, and will eventually be used in experiments employing extremely high-powered X-ray lasers. That could include the European XFEL, a laser currently under construction in Germany that will fire thousands of times faster than those at SLAC.

"The jets in our study took up to several millionths of a second to recover from each explosion, so if X-ray pulses come in faster than that, we may not be able to make use of every single pulse for an experiment," Stan said. "Fortunately, our data show that we can already tune the most commonly used jets in a way that they recover quickly, and there are ways to make them recover even faster."

Follow Kacey Deamer @KaceyDeamer. Follow Live Science @livescience, on Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus