Arctic Sea Ice Is at Near Record Lows, NASA Says

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

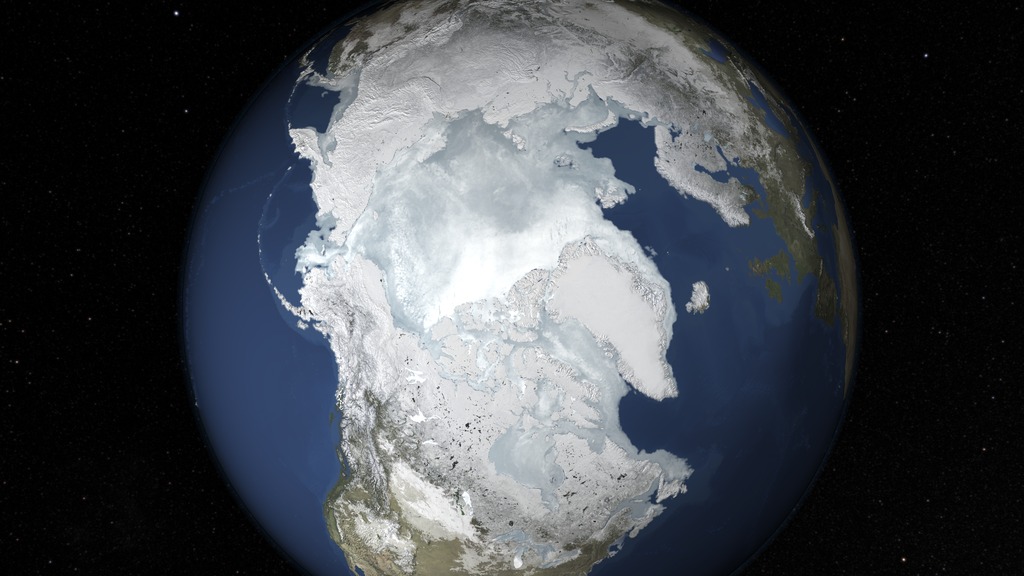

The ice covering the Arctic is at near record lows this year, and this icy deficit may impact weather around the world, NASA reports.

Every March, the Arctic's sea ice reaches its maximum cover, both in area and thickness, before it recedes to its yearly minimum in September. Live Science spoke with NASA scientist Walt Meier yesterday (March 25) to learn more about the low sea-ice level and what it means for the rest of the planet.

This winter has been extremely warm, Meier said. "Temperatures have been 10 to 15 degrees Fahrenheit [5.5 to 8.3 degrees Celsius] above normal [in the Arctic]. And we see that reflected in the very low sea-ice cover that generally grows to its maxima [maximum] around this time of year." [On Ice: Stunning Images of Canadian Arctic]

NASA has been collecting data on Arctic sea-ice extent (a term that refers to area and volume) since the late 1970s. Last year's maximum was the fourth-lowest on record, and 2016's sea ice extent is also among the lowest that scientists have seen in about 40 years.

The Arctic's sea-ice extent varies from year to year, but overall, researchers have seen a worrisome downward trend over time.

"We've lost about two Texases' worth of sea ice during the wintertime," Meier told Live Science. "In the summer, it's even more extreme. We've lost almost double that or more in terms of the area covered."

Furthermore, the ice is thinner now than it has been in past years. "So, we've lost about 50 percent of the volume of the sea ice, or the mass of the sea ice," since record keeping began, he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These dramatic changes don't stay in the Arctic. Typically, white-colored ice reflects about 80 percent of the sun's rays back into space. With less ice cover, the ocean absorbs a lot more of these rays, which warms the water.

"As you warm [the water] up, you're changing the contrast with the lower latitudes," Meier said. "And that contrast helps set up things like the jet stream and storm tracks and general weather patterns." As the Arctic warms, weather patterns in lower latitudes will also be affected, he noted.

For instance, cold air usually stays in the Arctic because of polar vortex winds, which make a circular, counterclockwise trip around the North Pole. But as sea-ice extent diminishes, the Arctic warms, high pressures build and the polar vortex weakens, allowing cold air to flow southward and cause fiercely cold winters, according to Weather Underground.

Within the next few days, NASA has two missions planned to take a closer look at the Arctic: Operation IceBridge and Oceans Melting Greenland, which has the rather fantastic acronym of OMG. These campaigns will take scientists to the Arctic and Greenland by land and air. Once there, they'll take measurements of the region's sea ice and glacier thickness.

"Basically, we can see these changes, but we don't fully understand the processes that are causing these changes," Meier said. "And so these aircraft flights that we're doing will allow us to collect very good … detailed data so that we can better understand these changes and better predict what is going to happen in the future."

People can follow both of the missions at NASA.gov/earth or on Twitter @NasaEarth.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus