This Summer's Arctic Sea Ice Is 4th Lowest on Record

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

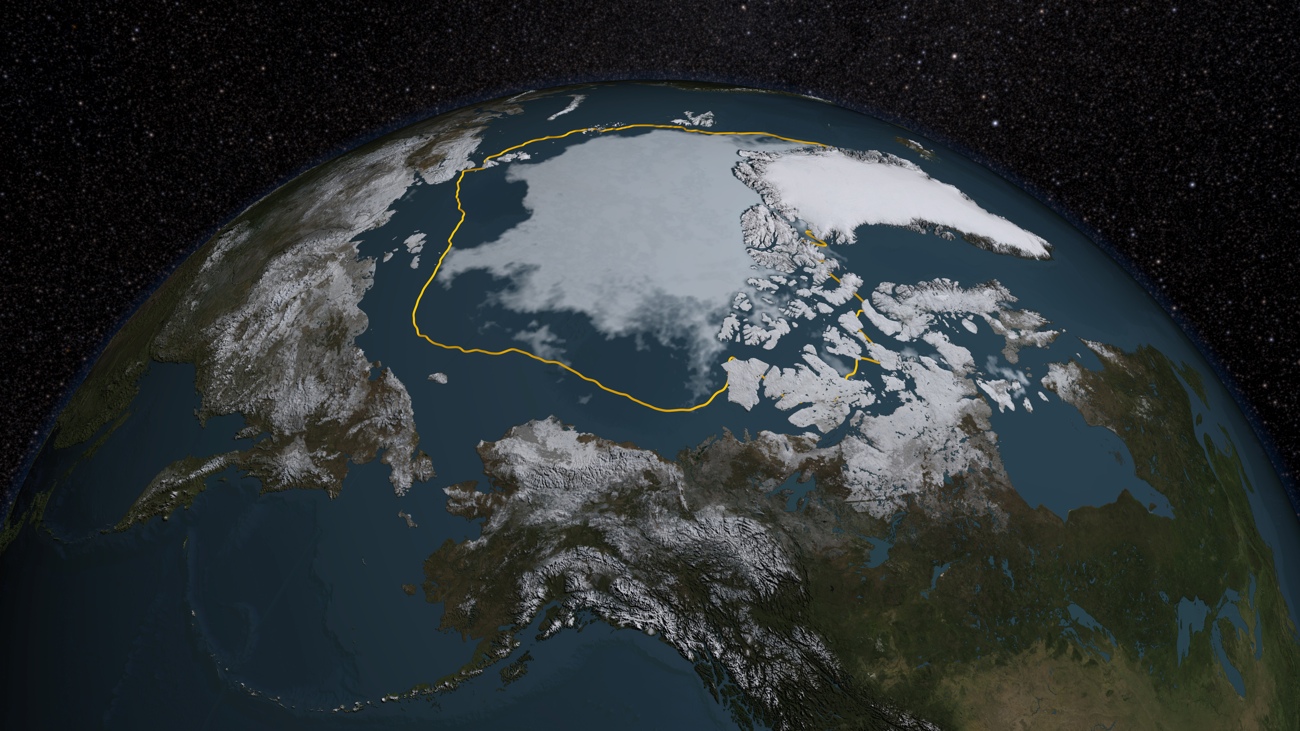

This year's minimum sea-ice extent in the Arctic was the fourth lowest since satellite observations began, NASA announced yesterday (Sept. 15).

The ice cap floating on the ocean in the Arctic shrinks and expands with the seasons, reaching its maximum extent in March and its minimum in September.

This summer, the Arctic sea ice retreated to 1.70 million square miles (4.41 million square kilometers), hitting its annual minimum on Sept. 11, according to a joint analysis by NASA and the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colorado. That's 699,000 square miles (1.81 million square km) less than the average minimum for all years between 1981 and 2010.

"This year is the fourth lowest, and yet we haven't seen any major weather event or persistent weather pattern in the Arctic this summer that helped push the extent lower as often happens," Walt Meier, a sea-ice scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a statement. "It was a bit warmer in some areas than last year, but it was cooler in other places, too." [Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice]

Accelerating melt

Arctic sea ice has been in decline since at least the 1970s due to climate change, and recent research reveals the thinning is accelerating. According to a study published in March in the journal The Cryosphere, September sea ice thinned 85 percent (from 9.8 feet to 1.4 feet, or 3 to 0.43 m) between 1975 and 2012. This thinning translates to less ice cover and more open ocean as the melt eats away at the ice pack.

Arctic sea ice hit a record minimum in 2012, when the ice covered a mere 1.32 million square miles (3.41 million square km). The low was driven partially by an August storm, according to NASA.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists aren't soothed by the slight bump in sea-ice minimums since 2012; the numbers are still low and represent an ongoing downward trend. In fact, Meier said, sea ice is becoming less and less resilient. There was no unusual weather fragmenting the ice pack this year.

"The sea-ice cap, which used to be a solid sheet of ice, now is fragmented into smaller floes that are more exposed to warm ocean waters," he said. "In the past, Arctic sea ice was like a fortress. The ocean could only attack it from the sides. Now, it's like the invaders have tunneled in from underneath and the ice pack melts from within."

2015 trends

In June, Arctic ice melted relatively slowly, NASA reported. But faster-than-normal melt began in July and continued through August. North of Alaska, an ice-free "hole" opened up in the ice pack covering the Beaufort and Chukchi seas, which allowed the ocean to absorb more heat, further eating away at the ice.

El Niño, an ocean-atmosphere pattern that warms the eastern Pacific near the equator, isn't known to have an effect on Arctic summer ice. But as the ice thins, that could change, Goddard climate modeler Richard Cullather said in the statement.

"Although we haven't been able to detect a strong El Niño impact on Arctic sea ice yet, now that the ice is thinner and more mobile, we should begin to see a larger response to atmospheric events from lower latitudes," Cullather said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus