'Lost' Roads of Ancient Rome Discovered with 3D Laser Scanners

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

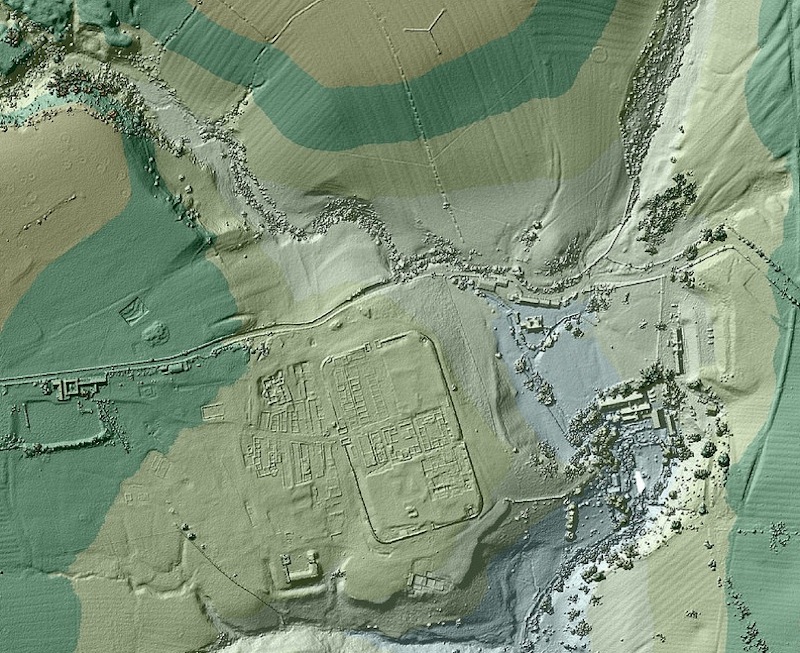

Laser scans of Britain's terrain may reveal weathered Roman roads that have been hidden for centuries across the countryside of northern England.

Over the past 18 years, the U.K.'s Environment Agency has used a technology called lidar to collect data for more than 72 percent of England's surface. This remote sensing technique bounces laser light beams off the ground to make 3D terrain maps that can peer below vegetation and reveal the contours of every ditch and boulder below.

The U.K.'s lidar maps were used primarily for environmental purposes, such as for planning flood defenses or tracking eroding coastlines. But last summer, the agency dumped all 11TB of its data sets onto the Survey Open Data website. [Roman Fort: See Images of the Long-Lost Discoveries]

The maps grabbed the attention of archaeologists and history buffs —among them, David Ratledge, a 70-year-old retired road engineer who has spent nearly five decades searching for ancient Roman roads, The Times of London reported.

After the Romans invaded Britain in the first century A.D., they built an impressive network of roads to secure their occupation. You can walk in the footsteps of Roman soldiers on a few surviving sections of these ancient highways today, but many routes have been stripped of their stones or they have been obscured by development and farmland.

These "lost" roads left some gaps in the history of Roman Britain. One mystery for Ratledge was, how did the Romans get from Ribchester to Lancaster? With access to the new maps, Ratledge thinks he has solved the puzzle. He traced an 11-mile (17 kilometers) road from Ribchester to the main north-south road at Catterall that then led to Lancaster.

"The road takes a very logical and economical route to join the main north-south road at Catterall and hence on to Lancaster," Ratledge wrote on the website of the Roman Roads Research Association. "Years of looking for a road via Priest Hill, White Chapel, Beacon Fell, Oakenclough and Street proved to be time spent in the wrong place!"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ratledge said a prominent stretch of a Roman rampart is even visible in Google Street View.

"How nobody —me included —spotted it is a mystery," he wrote.

Archaeologists Hugh Toller and Bryn Gethin have also used the lidar data to find four other roads, including a missing part of a Roman road called the Maiden Way, the U.K. Environment Agency said in a statement.

First developed in the 1960s, lidar has a variety of uses. In one of its best-known early applications, it helped NASA's astronauts study the surface of the moon during the Apollo missions. Today, it's been used to survey land for oil and gas companies, or to assess the damage of a disaster like the 2010 Haiti earthquake or Hurricane Sandy. It's even been used in an artistic capacity, to make haunting portraits of people in Ethiopia.

The technique has also become a useful tool for archaeologists who want to look for buried structures without breaking ground. In recent years, archaeologists have used lidar to discover the foundations of a lost city in the Honduran rainforest, mapped the sprawling ancient city of Angkor in Cambodia and revealed lost historic sites across New England.

In England, archaeologists aren't the only ones interested in the Environment Agency's terrain maps. The agency said utility companies might use the data to plan the construction of new infrastructure, and winemakers might even find the lidar maps useful when scouting potential plots for vineyards. "Minecraft" players have also requested the data sets to help them build virtual worlds.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus