New England's 'Lost' Archaeological Sites Rediscovered

Take a walk in the New England woods, and you may stumble upon the overgrown remains of a building's foundation or the stacked stones of a wall. Now, researchers have begun uncovering these relics from the air.

Examinations of airborne scans of three New England towns revealed networks of old stone walls, building foundations, old roads, dams and other features, many of which long were forgotten. These features speak to a history that Katharine Johnson, an archaeologist and study researcher, wants to see elucidated.

She and others know the story in broad strokes: After European settlers arrived in the 17th century, thousands of acres of forest were cleared to make way for much more intensive agriculture than that practiced by indigenous people. In the 19th century, people began leaving for industrial towns, allowing the forests to overtake their former farms.

"I think there is a general idea of what was happening, but it is not as well understood as it could be," Johnson, a doctoral student at the University of Connecticut, told LiveScience. [See the Aerial Images of 'Lost' Archaeological Sites in New England]

New Englanders have long known about these relics of the agricultural past. But Johnson and William Ouimet, her adviser and co-author, harnessed a new way to look for them, one that has proved useful in other places.

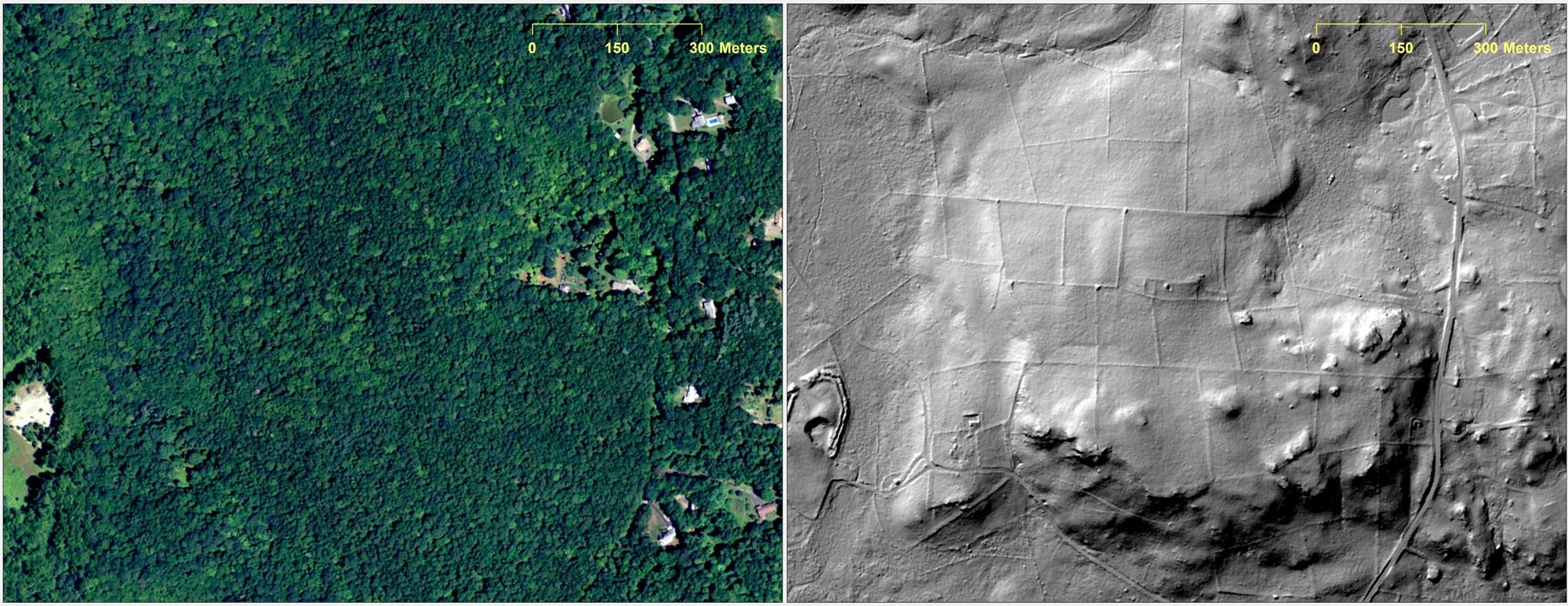

They looked at publicly available data collected by using a remote-sensing technology known as light detection and ranging (LiDAR). These scans map the surface below using laser pulses, and they make it possible for researchers to look below tree cover. LiDAR has increasingly been used in archaeology of late, with researchers, aided by the technology, finding the ancient capital of the Khmer Empire, Angkor, was even more massive than previously thought. LiDAR has also revealed a lost city beneath the Cambodian jungle (near Angkor) as well as evidence of Ciudad Blanca, a never-confirmed legendary metropolis, hidden by Honduran rain forests.

In the new study, Johnson and Ouimet focused on parts of three rural towns: Ashford, Conn.; Tiverton, R.I.; and Westport, Mass. In the scans, stone walls showed up as thin linear ridges, forming enclosures that were likely once fields, lining old thoroughfares, and clustering around the foundations at the heart of old farmsteads.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The LiDAR also picks up on modern features, leading to potential confusion. Old building foundations can resemble modern swimming pools, for example. To verify what they see in LiDAR data, Johnson and Ouimet have been visiting sites.

This new information is best used in combination with historical documents, Johnson said.

"On a historical map, you might see just one dot, and a person's name representing a farmstead, but if you compare that with the LiDAR you might see all of the buildings, in addition to the layout, and the fields, and the road leading to it," she said.

Sometimes the past lives on in the modern landscape. Many stone walls that showed up in the scans of Westport, Mass., delineated property lines, both in modern times and on a map from 1712, she said.

This research will be detailed in the March issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science, and is now available online.

Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus