Buried or Open? Ancient Eggshells Reveal Dinosaur Nesting Behaviors

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The fragile remains of 150-million-year-old eggshells are helping researchers figure out what kinds of nests dinosaurs created for their eggs, according to a new study.

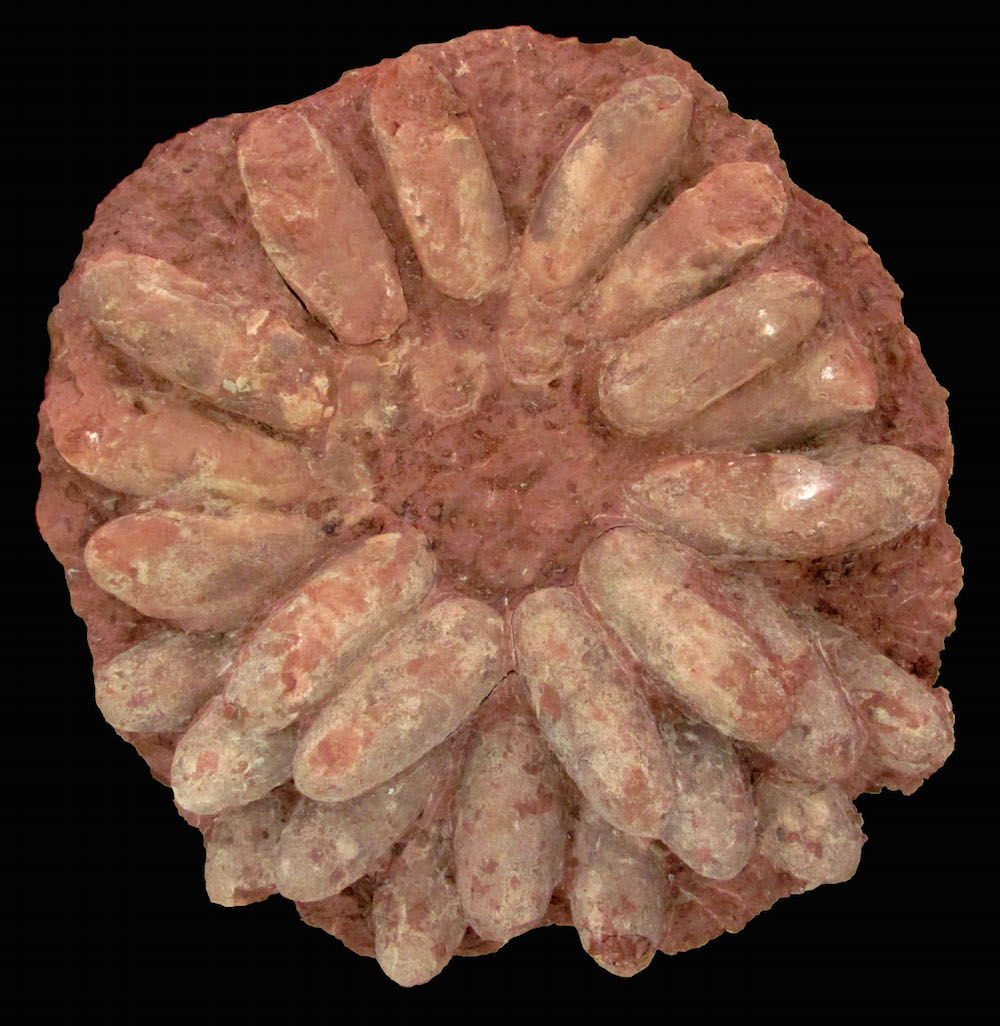

A comprehensive look at 29 types of dinosaur eggs suggests that most dinosaurs buried their eggs in nests covered with dirt and vegetation, a tactic also used by modern-day crocodiles.

But some small theropods (mostly meat-eating, bipedal dinosaurs) that were closely related to birds used another strategy: They laid their eggs in open nests, much like most birds do today, the researchers found. [Image Gallery: Dinosaur Daycare]

"The evolution of open nests and brooding behavior could have allowed small theropod dinosaurs, and obviously birds, to move to other nesting locations other than on the ground," which may have helped their evolutionary success, said study co-researcher Darla Zelenitsky, an assistant professor of paleontology at the University of Calgary in Canada.

Researchers have spent years piecing together limited evidence about how dinosaurs raised their young, but there are few dinosaur egg fossils to study, said study lead author Kohei Tanaka, a doctoral student in the faculty of science at the University of Calgary.

"Dinosaur nest structures and nesting materials are usually not preserved in the fossil record," Tanaka said in a statement. "In the past, this lack of data has made working with dinosaur eggs and eggshells extremely difficult to determine how dinosaurs built their nests and how the eggs were incubated for hatching young."

Luckily, researchers can compare the fossilized eggs of dinosaurs to those of the dinosaur's closest living relatives: crocodiles and birds. Crocodiles bury their eggs in nests on the ground and cover them with sand, dirt and rotting vegetation, which keeps the eggs warm. In contrast, birds usually lay their eggs in open nests, and brood on them during incubation.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

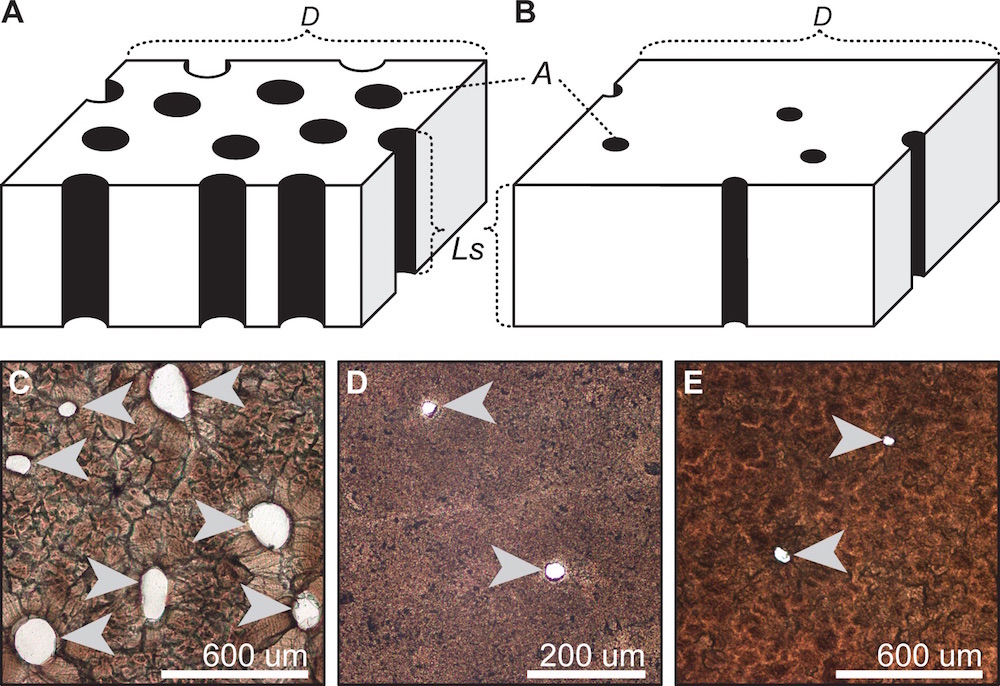

These modern eggs — specifically, the number and size of the pores in their shells — gave researchers clues about the nest type. They collected data on the eggs and nests of more than 120 modern species of birds and crocodiles, and found stark differences between the two. [Album: Discovering a Duck-Billed Dino Baby]

Buried eggs tended to have a high porosity, or larger and more holes in the shell that allow for vapor and gas exchange between the outside world and the embryo. However, burying the eggs helps to retain their humidity and moisture as the embryo develops inside, Zelenitsky told Live Science.

Meanwhile, eggs in open nests (laid by brooding birds) tended to have lower porosity, "so loss of moisture is not as much an issue because gas diffusion is lower,"Zelenitsky said.

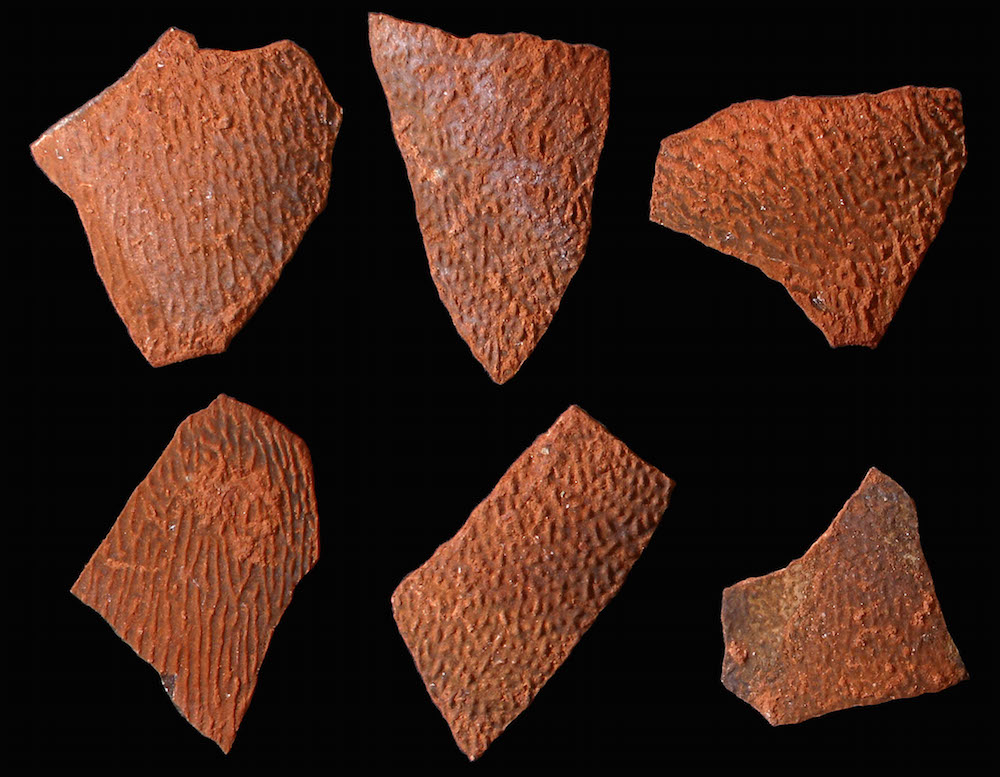

Once the researchers figured out that buried eggs tend to have high porosity, and open-nest eggs tend to have low porosity, the researchers turned their attention to the fossilized dinosaur eggs. The eggs were ancient, ranging from 150 million to 70 million years old, but they still retained crucial details, such as porosity.

Most dinosaurs, such as the long-necked sauropods, less-developed theropods and possibly the plant-eating ornithischians, had high-porosity eggs, and likely buried their eggs in nests, the researchers found. But more developed theropods, such as the maniraptorans, had eggs with low porosity, and probably laid their eggs in open nests, they said. It's unclear whether these small theropods also brooded on top of their nests, but there are fossils of small dinosaurs doing just that, which suggests that some did, Zelenitsky said.

However, these well-developed small theropods didn't lay their eggs exactly like today's modern birds. Other fossil evidence shows that early open-nesting dinosaurs still partially buried their eggs, she said.

"It was probably not until modern-looking birds that open nests with fully exposed eggs came to be," Zelenitsky wrote in a statement.

The finding suggests that nest types, and probably incubation styles, changed over time as dinosaurs evolved.

"We don't have eggs for every species of dinosaur, but the more primitive dinosaurs have these buried nests, and the more advanced maniraptoran theropods, which are the closest relatives of birds, laid open-nest eggs that are exposed," Zelenitsky said.

The findings were published online today (Nov. 25) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus