Doomsday Clock Set at 3 Minutes to Midnight

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The world is "3 minutes" from doomsday.

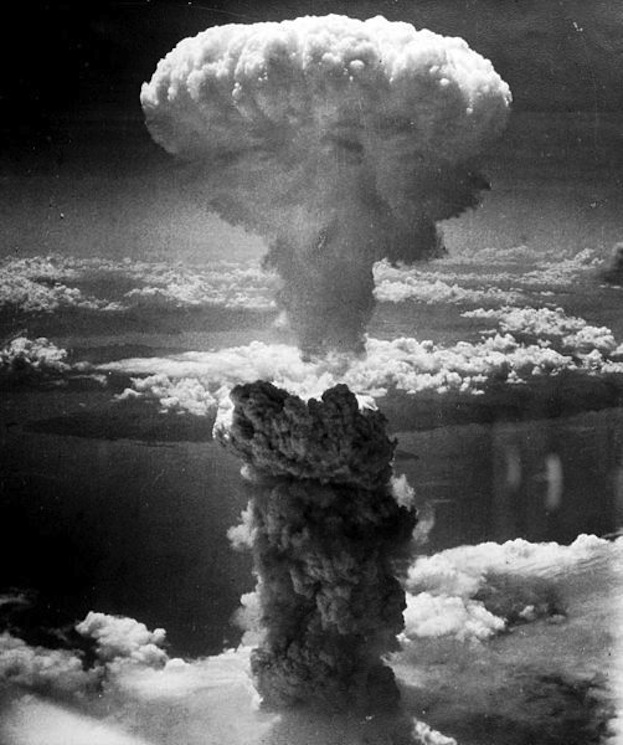

That's the grim outlook from board members of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Frustrated with a lack of international action to address climate change and shrink nuclear arsenals, they decided today (Jan. 22) to push the minute hand of their iconic "Doomsday Clock" to 11:57 p.m.

It's the first time the clock hands have moved in three years; since 2012, the clock had been fixed at 5 minutes to symbolic doom, midnight. [End of the World? Top Doomsday Fears]

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists doesn't use the clock to make any real doomsday predictions. Rather, the clock is a visual metaphor to warn the public about how close the world is to a potentially civilization-ending catastrophe. Each year, the magazine's board analyzes threats to humanity's survival to decide where the Doomsday Clock's hands should be set.

Experts on the board said they felt a sense of urgency this year because of the world's ongoing addiction to fossil fuels, procrastination with enacting laws to cut greenhouse gas emissions and slow efforts to get rid of nuclear weapons.

"We are not saying it is too late to take action but the window for action is closing rapidly," Kennette Benedict, executive director of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, said in a news conference this morning in Washington, D.C. "We move the clock hand today to inspire action."

For instance, if nothing is done to reduce the amount of heat-trapping gasses, such as carbon dioxide, in the atmosphere, Earth could be 5 to 15 degrees Fahrenheit (3 to 8 degrees Celsius) warmer by the end of century, said Sivan Kartha, a senior scientist at the Stockholm Environment Institute.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some people might not feel alarmed when they see those numbers; they might normally experience that kind of temperature swing in the course of a single day, Kartha said. But, he said a temperature increase of that magnitude was enough to bring the world out of the last ice age, and it will be enough to "radically transform" the Earth's surface in the future.

Sharon Squassoni, another board member and director of the Proliferation Prevention Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said nuclear disarmament efforts have "ground to a halt" and many nations are expanding, not scaling back, their nuclear capabilities. Russia is upgrading its nuclear program, India plans to expand its nuclear submarine fleet, and Pakistan has reportedly started operating a third plutonium reactor, Squassoni said.

She said the United States has good rhetoric on nuclear nonproliferation, but at the same time is in the midst of a $335 billion overhaul of its nuclear program. (That figure seems to come from a Congressional Budget Office report from December 2013.)

"The risk from nuclear weapons is not that someone is going to press the button, but the existence of these weapons costs a lot of time, effort and money to keep them secure," Squassoni said, adding that there have been troubling safety discrepancies reported in recent years at power plants.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was founded in 1945 by scientists who created the atomic bomb as part of the Manhattan Project and wanted to raise awareness about the dangers of nuclear technology. The Doomsday Clock first appeared on a cover of the magazine in 1947, with its hands set at 11:53 p.m.

The clock's hands shifted quite a bit over the following seven decades. They were closest to midnight in 1953, set at 11:58 p.m., after both the United States and the Soviet Union conducted their first tests of the hydrogen bomb. The clock's hands were pushed all the way back to 11:43 p.m., 17 minutes to midnight, in December 1991, after the world's superpowers signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, which at the time, seemed like a promising move toward nuclear disarmament.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus