Drought-Tracking Satellite to Blast Off This Month

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A new satellite expected to launch this month will improve drought monitoring in the United States and around the world, NASA scientists said Thursday (Jan. 8).

The Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) satellite will provide the best maps yet of soil moisture levels from pole to pole, mission scientists said. Soil moisture is one of the key factors in estimating drought severity; it also influences local weather, adds to hazards such as flooding, and plays a role in how plants store and release carbon.

"I think the next couple of years are going to be very exciting for Earth science," Dara Entekhabi, SMAP science team lead and an environmental engineer at MIT, said Thursday during a NASA media briefing.

Data from the satellite will track global soil moisture levels for the top 2 inches (5 centimeters) of Earth's surface every two to three days. For the first time, scientists will get a bird's-eye view of drought patterns; for instance, they'll watch where droughts begin and end, and how droughts spread across large areas. The mission is planned to last three years, at a cost of $916 million (including launch), but the instruments could last several years longer, mission scientists said. [Dry and Dying: Images of Drought]

The SMAP satellite, which will be carried aloft by a Delta II rocket, is scheduled to launch Jan. 29 from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

Eyes on dry

The soil moisture maps will help farmers who depend on rain to irrigate crops, the scientists said. However, the satellite can't tell farmers whether a particular field is ready to plant — the maps can't detail features as small as a typical farm plot. The resolution will be about 6 miles (10 kilometers), according to NASA.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers will also examine links between soil moisture and weather, such as rainfall and temperature. Soil moisture affects the weather through evaporation, because when the sun's energy bakes water out of the soil, it cools the surface — the same cooling effect sweating has on the body, Entekhabi said.

The soil moisture maps could also help improve flood warnings because forecasters will know how wet the ground is before an intense storm. Less than 1 percent of Earth's water is stored in soil — most is in the oceans and frozen in ice — but soil moisture determines how much freshwater is in rivers and lakes, Entekhabi said.

"It's a tiny amount, but it's rather important and very active," Entekhabi said.

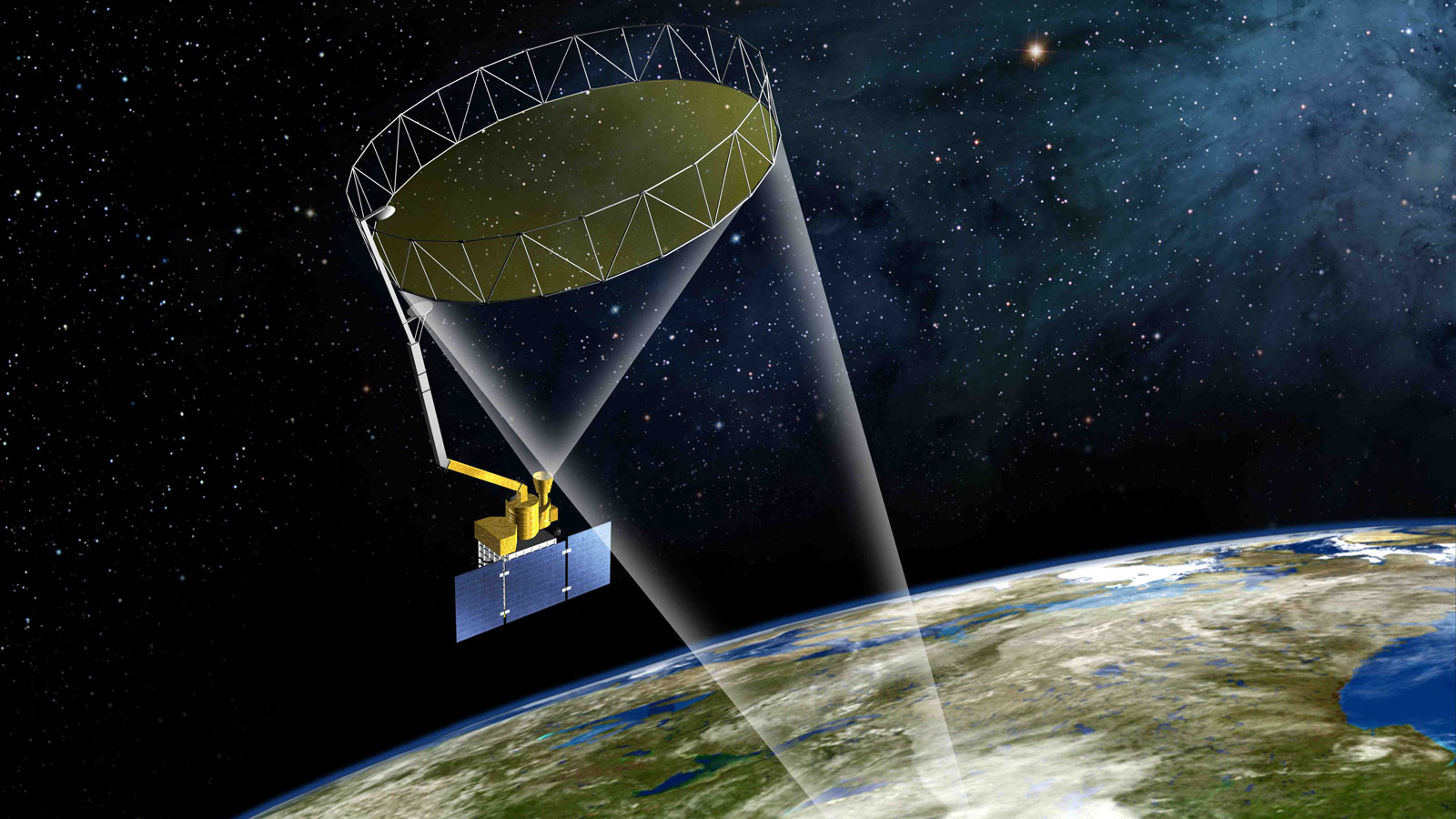

The SMAP satellite's most prominent feature is its rotating mesh antenna, which measures nearly 20 feet (6 meters) across — the largest ever deployed in space. For launch, the antenna stows into a nook the size of a tall trash can. Mounted on a long arm like a giant beach umbrella, a motor spins the antenna at 14.6 revolutions per minute. A radar and radiometer complete the main parts.

"The spacecraft looks somewhat like the tail wagging the dog with this very large antenna," said Kent Kellogg, SMAP project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

The radar beams microwaves at Earth, and the radiometer measures Earth's emitted microwave radiation. Changes in the signals indicate changes in soil moisture and whether the soil is frozen.

SMAP was one of five Earth observation satellites that NASA targeted for blast off in 2014. The space agency's Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 satellite, Global Precipitation Measurement Core Observatory and ISS-RapidScat all made it off the ground in 2014. A scheduled Jan. 6 launch for the Cloud-Aerosol Transport mission was scrubbed this week by SpaceX and is rescheduled for Saturday (Jan. 10).

The five craft are intended to help NASA fill gaps in its monitoring of the water, energy and carbon cycles, said Christine Bonniksen, NASA program executive for SMAP.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus