Thousands of Eocene Shark Teeth Found in Canadian Arctic

The stark, barren landscape of Banks Island in Canada has yielded an unexpected find — more than 8,000 shark teeth that date back millions of years, and have now been described in a study.

In the summer of 2004, study author Jaelyn Eberle, a paleontologist and associate professor of geological sciences at the University of Colorado at Boulder, ventured out with her research team to Banks Island, which is Canada's westernmost Arctic island. The researchers were hoping to find fossils of mammals, but after spending about a week there, they had not found any. Moreover, the weather was cold and the researchers' tents were covered with snow, Eberle said.

This really is the pits, Eberle remembers thinking at the time.

But then the team started finding the teeth of ancient sharks.

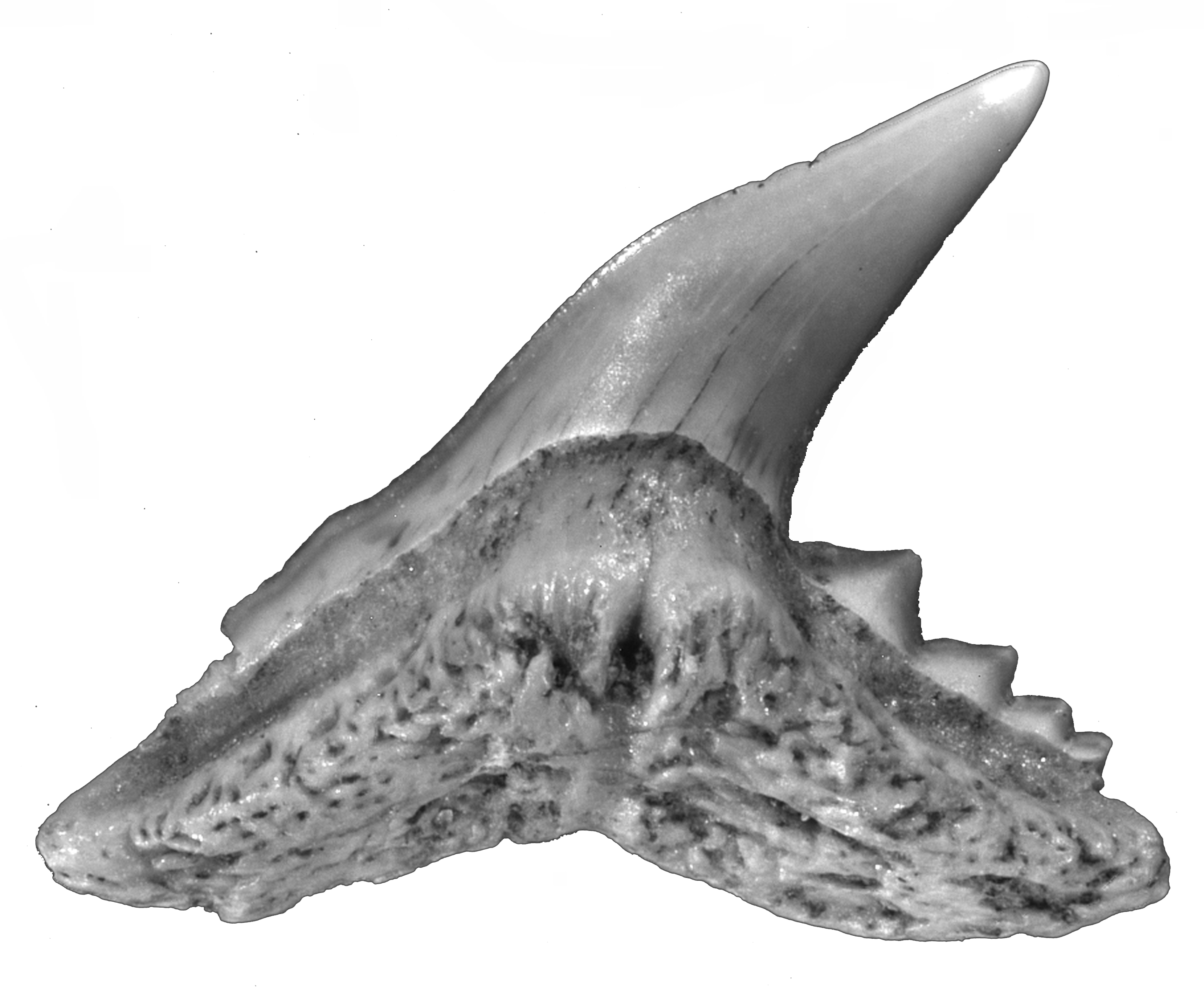

"Probably the biggest surprise, at least at first, was that most of them — literally thousands of these things — belong to just two shark genera, and they are both within the sand [tiger] type of sharks," Eberle said. The two genera are Striatolamia and Carcharias, according to the paper. [Image Gallery: Great White Sharks]

The researchers went back to the island in 2010 and 2012 to collect more shark teeth. They estimate that the teeth date to the late-early or middle Eocene epoch, or about 53 to 38 million years ago, according to the study, published in the November issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

The modern relatives of the two genera identified by the researchers live in warm, tropical waters, Eberle told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Two of the teeth the researchers found belonged to an extinct species of sand shark, Odontaspis winkleri. And about 1 percent of the teeth belonged to species within the genus Physogaleus, related to sharpnose and tiger sharks, according to the study.

The researchers wondered why the diversity of the shark teeth they found was so low. "We have got four genera so it is not a lot of diversity, and yet we know during this time, the early Eocene, the climate was warmer than at any other time since the extinction of dinosaurs, and we know the Arctic was much warmer in the early Eocene [than it is now]," Eberle said. The warmer water would be expected to hold a higher diversity of shark species than what the researchers found.

The investigators estimated that the mean annual temperature in the Arctic at that time ranged from 8 to 14 degrees Celsius (46 to 57 degrees Fahrenheit) in the winter, and between 20 and 25 C (68 to 77 F) in the summer. This means that winter temperatures were above freezing.

There were alligators and giant tortoises living in the eastern Arctic at that time, Eberle said.

The researchers' analysis of the shark teeth revealed that the salinity of the coastal waters was very low at the time, Eberle said. In fact, the degree of salinity was closer to freshwater than that of a modern ocean, which many shark species could not tolerate, she said. This may explain the low shark diversity.

"You don't get a lot of sharks that can tackle that kind of low salinity," she said.

Although Eberle is primarily a mammal paleontologist, she said she now has a new appreciation for sharks after examining their teeth.

"They are pretty, they are really interesting," she said. The surface of the teeth can be shiny and white, or bluish or grayish, she said.

Follow Agata Blaszczak-Boxe on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.