Ancient Turtle Was as Big as Small Car

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

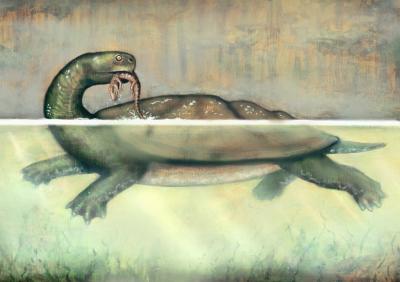

A turtle the size of a small car once roamed what is now South America 60 million years ago, suggests its fossilized remains.

Discovered in a coal mine in Colombia in 2005, the turtle was given the name Carbonemys cofrinii, which means "coal turtle." It wasn't until now that the turtle was examined and described in a scientific journal; the findings are detailed online today (May 17) in the Journal of Systematic Paleontology.

The researchers say C. cofrinii belongs to a group of side-necked turtles known as pelomedusoides. The turtle's skull, roughly the size of an NFL football, was the most complete of the fossil remains.

In addition to its colossal size, the turtle would have been equipped with massive, powerful jaws, meaning it could've eaten just about anything in its range, from mollusks (a group that includes snails) to smaller turtles and even crocodiles, the researchers noted.

Its all-encompassing appetite as well as its need for a large range to satiate its food requirements may explain why no other turtle of this size has been found at the site. [Gallery: The World's Biggest Beasts]

"It's like having one big snapping turtle living in the middle of a lake," study researcher Dan Ksepka, of North Carolina State University, said in a statement. "That turtle survives because it has eaten all of the major competitors for resources."

While the researchers have found bite marks on the remains of other side-necked turtles in the area, suggesting they were preyed upon by crocodilians, such predators would not have messed with this coal mine turtle. "In fact smaller crocs would have been easy prey for this behemoth," Ksepka said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers also discovered a turtle shell nearby that they believe belonged to the same species; the shell would've been large enough to double as a kiddy swimming pool, they noted, as it measured some 5 feet 7 inches (172 centimeters) across.

"We had recovered smaller turtle specimens from the site. But after spending about four days working on uncovering the shell, I realized that this particular turtle was the biggest anyone had found in this area for this time period — and it gave us the first evidence of gigantism in freshwater turtles," Edwin Cadena, also of North Carolina State, said in a statement.

In fact, this big turtle appeared 5 million years after the dinosaurs vanished, at a time when gigantism was relatively common in this part of South America. For instance, the largest snake ever discovered, measuring 45 feet (14 meters) long and called Titanoboa cerrejonensis, lived there, also about 60 million years ago.

A combination of factors, including abundant food, fewer predators, vast habitat and climate change, would have worked together to allow turtles and other animals to balloon to such relatively gargantuan sizes, the researchers suggest.

For instance, the warm weather would've been beneficial for such ectotherms that rely on their surroundings to regulate their body temperature.

"The environment seems to have been tropical based on fossil plants found at the site," Ksepka told LiveScience. "And the turtle appears to have been adapted to spending most of its time in the water, though coming ashore to lay eggs would be part of its life cycle."

Another turtle discovered in this coal mine may have evolved an adaptation to protect itself from these giants; the turtle, called Cerrejonemys wayuunaiki, sported an extra-thick shell, about the thickness of a high-school textbook.

The research, funded by the Smithsonian Institute and the National Science Foundation, will be detailed in the June 2012 print issue of the Journal of Systematic Paleontology.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus