Illuminating! Ancient Slab May Be Sundial-Moondial

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A strange slab of rock discovered in Russia more than 20 years ago appears to be a combination sundial and moondial from the Bronze Age, a new study finds.

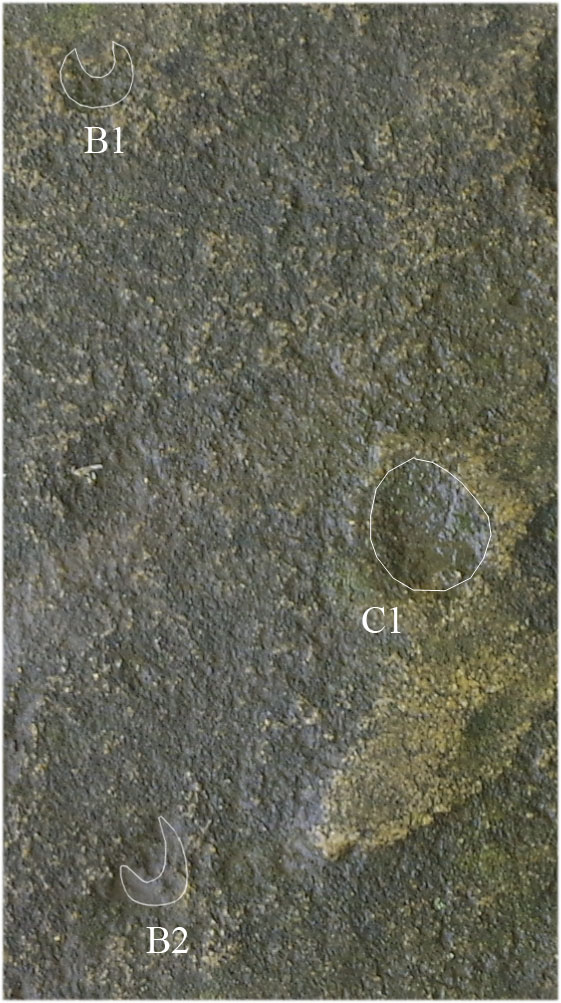

The slab is marked with round divots arranged in a circle, and an astronomical analysis suggests that these markings coincide with heavenly events, including sunrises and moonrises.

The sundial might be "evidence of attempts of ancient researchers to understand patterns of apparent motion of luminaries and the nature of time," study researcher Larisa Vodolazhskaya of the Archaeoastronomical Research Center at Southern Federal University in Russia told Live Science in an email. [See Images of the Bronze Age Sundial-Moondial]

Ancient instrument

Last year, Vodolazhskaya and her colleagues analyzed a different Bronze Age sundial, this one found in Ukraine, and discovered it to be a sophisticated instrument for measuring the hours. The work caught the eye of archaeologists in Rostov, Russia, who knew of a similar-looking artifact found in that area in 1991. That slab had been sitting in a museum in Rostov ever since its discovery, and had never been thoroughly studied.

The Rostov slab was found over the grave of a man of about 50, and dates back to the 12th century B.C., similar in age to the one found in Ukraine. Sundials from this era have also been discovered in ancient Egypt, including in the tomb of the pharaoh Seti I.

By studying the geometry of the Rostov slab, Vodolazhskaya and her colleagues discovered that the carved circles, which are arranged in a pattern spanning about 0.9 feet (0.3 meters) in diameter, correspond with the sunrises at equinoxes (days of the year when night and day are equal in length) and solstices (days of the year when day or night are at their longest).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And the Bronze Age people who created the sundial weren't only interested in the sun. The circles that didn't correspond to solar movements were linked to lunar wanderings. Because of the angle of the moon's orbit, our lone satellite goes through an 18.6-year cycle. During this cycle, when it rises, its position shifts from southerly to northerly, and its movements across the sky are relatively high and low. The Rostov slab tracks these movements with circular carvings indicating the southernmost and northernmost moonrises of these "low" and "high" moons.

Savvy civilization

The slab was found at a Bronze Age Srubna or Srubnaya site, a culture which flourished on the steppes between the Ural Mountains and Ukraine's Dneiper River. The Srubna people may have used the sun/moondial to time their annual rituals or to organize their work lives. Or, Vodolazhskaya said, the artifact may be the work of Bronze Age scientists.

"One cannot exclude a purely research appointment of such instruments. … In ancient times, people were just as inquisitive as modern physicists and astronomers," Vodolazhskaya said.

In combination with the Ukraine sundial and other Bronze Age artifacts, the find suggests that the people in the Northern Black Sea region were astronomically savvy, Vodolazhskaya said, with technology on par with what was seen in ancient Egypt around the same time. The new study has not yet been peer-reviewed, but is available on the prepublication website arXiv.org.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus