Pretty in Pink: New Moon Rock Reveals Rosy Secret

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A mysterious new moon rock has revealed its secrets to scientists on Earth, who cooked up a copy of the unattainable pink crystals in a searing hot crucible.

The new moon rock was found five years ago by Carlé Pieters, a planetary scientist at Brown University in Rhode Island, and the principal investigator for NASA's Moon Mineralogy Mapper (called M3). The M3 spectrometer, which was carried on India's Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft, pored over the moon's surface, hunting for unusual minerals and for water by picking up reflected light. Different minerals have distinct reflected light signals.

At two lunar craters, the signals indicated an extremely rare variety of the mineral spinel. On both the Earth and moon, spinel comes in a range of chemical formulas, but this crystal was ur-spinel — only magnesium, aluminum and oxygen. (Other spinels sub in iron or chromium for the magnesium and aluminum.) Gem-quality red spinel resembles ruby or garnet, and such shimmering red gems are part of Britain's crown jewels.

"This kind of pink spinel is very unique to the moon," said lead study author Tabb Prissel, a planetary geologist at Brown.

Based on the M3 signals, the researchers could guess at the rock's appearance. Pink spinel crystals studded a field of plagioclase minerals, called anorthosite feldspar, common to the moon. Feldspar gives the moon its white glow. [Gallery: Hidden Rainbows in Ordinary Rocks]

Shine on, pink moon

To find out why there was such a strangely pure pink spinel on the moon, the team created the unique rock in a laboratory. Forging the crystals has helped provide insight into the geologic conditions that formed the rare mineral. The findings will be published Oct. 1 in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

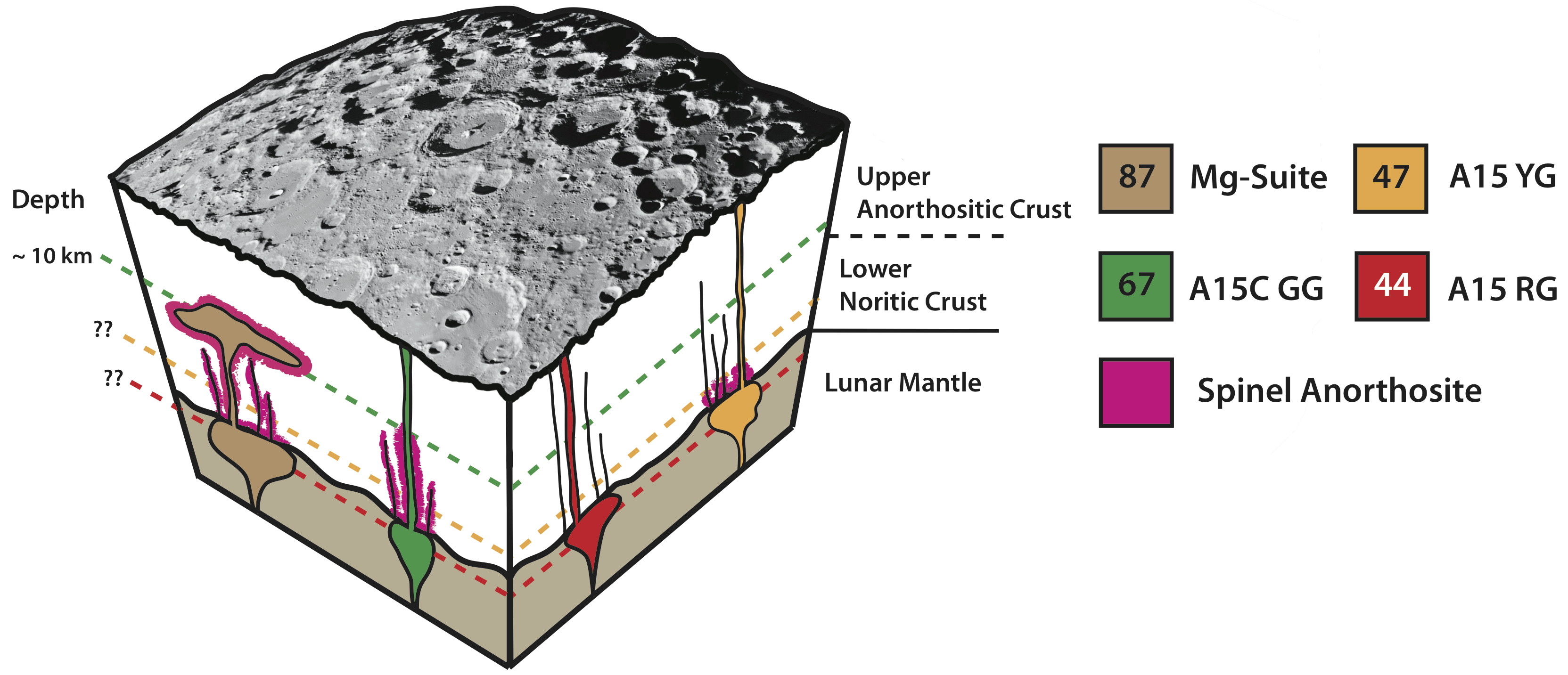

The results suggest that the pink spinels are related to ancient, magnesium-rich rocks brought back by Apollo astronauts, a distinct set of samples now called the Mg-suite (Mg is for magnesium) rocks. These rocks are more than 4.1 billion years old.

The Mg-suite rocks have lots of magnesium, potassium and rare-earth elements relative to other moon rocks. They were once part of the moon's original crust, but have been battered and pulverized by meteorite impacts.

"The Mg-suite anorthosites represent the onset of ancient lunar magmatism, but we can't find the lavas anywhere," on the moon's surface, Prissel told Live Science, referring to volcanic activity. "If the pink spinel is linked to these ancient rocks, this is very cool, because then we can get a better idea of where Mg-suite magmatism was occurring on the moon," he said.

To find out how the pink spinel formed, Prissel mixed up various powders that matched the composition of moon rocks brought back by astronauts and cooked them until they melted, testing the samples at various pressures to mimic what happens when rocks cool at different depths inside the moon's crust. He discovered that the best way to make a pink spinel anorthosite was to start with two parents: one resembling moon crust and one similar to the Mg-suite rocks. The parents suggest that Mg-suite molten rock mixed with moon crust before it cooled to create the pink spinel anorthosite.

Based on the tests, the researchers think the pink moon rocks are intrusive rocks, which cool slowly inside the crust from magma, or molten rock.

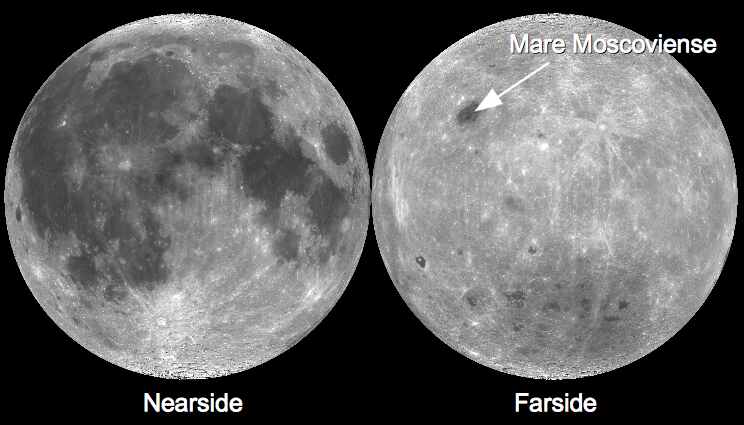

Both spinel outcrops are small, less than a mile in size. On the moon's far side, the rock is exposed in the rim of the Moscoviense Basin. On the near side, a similar rock can be found in Theophilus crater within the Nectaris Basin. Craters are like windows into the deeper layers of the moon's crust, carving out older rock layers.

"The moon serves as a geologic time capsule," Prissel said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus