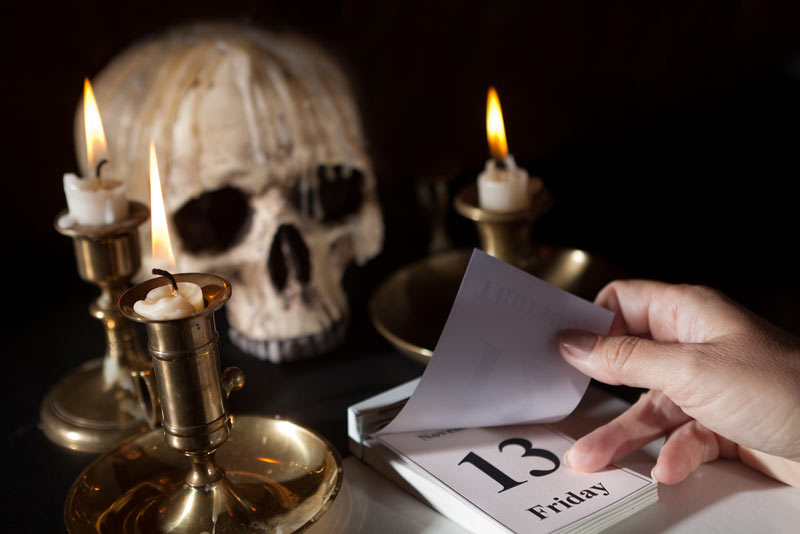

The Origins of Unlucky Friday the 13th

Today, the phrase "Friday the 13th" rolls off the tongue, instinctively linked to bad luck, strange happenings and a hockey-masked murderer in a slasher flick of the same name. But before Jason Voorhees made his mark in 12 films about the infamous day, how did the superstition come to exist?

No expert can verify the origins of Friday the 13th. But the first written references to its wickedness appear around the mid-19th century when William Fowler, a U.S. Army captain, founded the Thirteen Club — a group of 13 men in Manhattan devoted to proving the superstitions were false. The Club grew and at some point apparently included five former U.S. presidents as honorary members.

The men gathered for the first time on Friday, Jan. 13, 1881, and their exploits — described in newspapers of the time — included walking under ladders, breaking mirrors and dining as a group in room 13.

From that point on, more definitive references to Friday the 13th began to emerge. In 1907, British stockbroker Thomas Lawson wrote "Friday the 13th," a book about a rogue businessman's attempt to crash the stock market on that day. The book sold almost 28,000 copies in its first week, and this idea of a link between bad luck and a bad stock market continued throughout the 1920s. [13 Freaky Facts About Friday the 13th]

But to truly deconstruct the day's connotations, folklore historians like Donald Dossey, author of "Holiday Folklore, Phobias and Fun" (Outcome Unlimited Pr, June 1992), suggest that Friday the 13th actually comes from two separate superstitions rooted in ancient history: the evil of the number 13 and the bad luck of Friday — each with a string of mythical narratives of their own.

Thirteen is a loaded number in cultural, religious and mythic history. Nordic mythology tells a tale of the 12 gods gathering for a dinner party, when a 13th guest walked in uninvited. The guest was Loki, a mischievous, trickster god. Loki took his bow and arrow and shot Balder the Beautiful, a god who represents joy and gladness, the story goes. Balder's death brought darkness and mourning into the world — and possibly lent the concept of a dinner party with 13 guests a shade of misfortune.

In Christianity, some believe that Judas — one of Jesus' 12 apostles — arrived as the 13th guest to the Last Supper. The next morning, it was Judas who betrayed Jesus, leading to his arrest and crucifixion.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But some say the number 13 is also considered unlucky because of its place after the number 12. Thirteen is just "a little beyond completeness," Thomas Fernsler, a math and policy scientist at the University of Delaware who also goes by the name Dr. 13, told National Geographic last year. "The number becomes restless or squirmy," Fernsler added.

That's because in numerology, or the study of the symbolism of numbers, 12 is associated with completeness: whole, perfect and harmonious, as seen in the 12 apostles, 12 Olympic Gods, 12 animals in the Chinese horoscope and 12 months in the Gregorian calendar. Thirteen — by default — is awkward, ungainly and odd.

Friday's associations have a weaker background. It's been suggested that Friday carries certain meaning in Christian tradition. For example, as described in the creation story, Eve gave Adam the poisonous fruit that had them exiled from God's Garden of Eden on the seventh day of creation — Friday. It was on Friday that Cain killed his brother Abel in the myth of the two brothers. And it was Friday that Jesus was crucified, a day now known as Good Friday.

Despite the ambiguity of its origins, the buzz around Friday the 13th continues. This June's Friday the 13th falls under a full moon; that kind of coincidence won't happen again until August 2049.

Follow Jillian Rose Lim on Twitter & Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.