Tiny Ancestor of Lions, Tigers & Bears Discovered (Oh My!)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Lions, tigers, bears and even loyal pups and playful kitties all come from the same line of carnivorous mammals, a lineage whose origins are lost in time. Now, scientists have discovered one of the earliest ancestors of all modern carnivores in Belgium.

The new species, Dormaalocyon latouri, was a 2-pound (1 kilogram) tree-dweller that likely fed on even smaller mammals and insects.

"It wasn't frightening. It wasn't dreadful," said study researcher Floréal Solé, a paleontologist at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels. What it was, Solé said, is a clue to the beginnings of today's toothy beasts. [In Photos: Mammals Through Time]

"It is one of the oldest carnivorous mammals which is related to present-day carnivores," Solé told LiveScience.

Carnivore history

All modern carnivores descend from a single group, one of four groups of carnivorous mammals found in the Paleocene and Eocene periods, Solé said. The Paleocene ran from 66 million to 56 million years ago, and the Eocene followed from 56 to 33.9 million years ago.

The carnivoraforms, as they're known, appear widespread during the Eocene, but without earlier fossils, paleontologists are unsure about their origins. Solé and his colleagues examined fossils from the very earliest Eocene, about 56 million years ago, from Dormaal, Belgium, east of Brussels.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The site was first discovered in the 1880s and has yielded 40 species of mammals over the years. Richard Smith, also of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, and a colleague of Solé's, has sifted nearly 14,000 teeth from the soil in Dormaal.

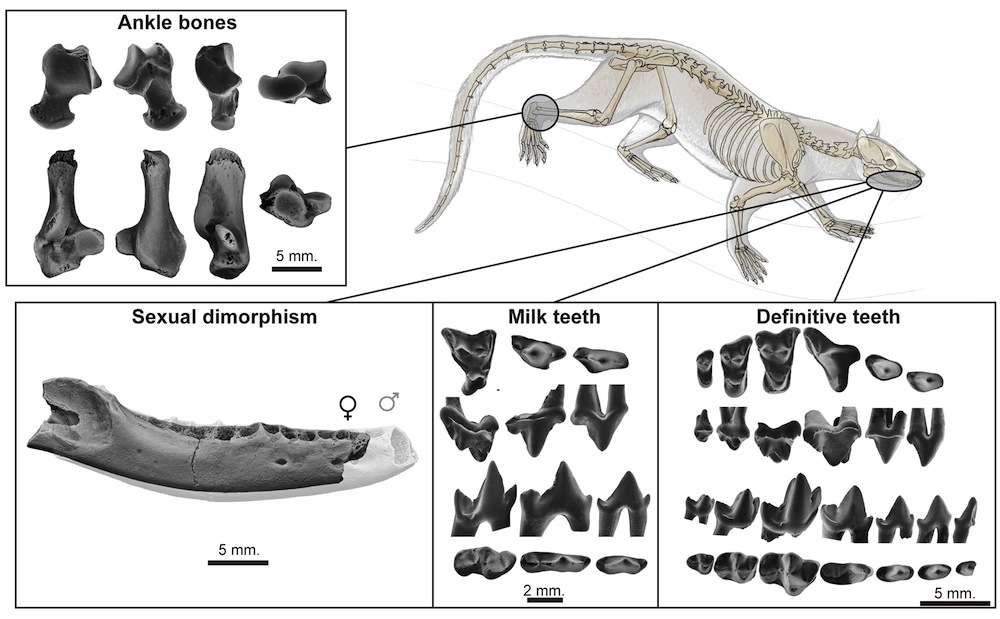

Among them are 280 new specimens of teeth from a species hinted at previously from only two molars. With the new information from the teeth (including baby teeth from juveniles) and some ankle bones, Solé, Smith and their colleagues described this species today (Jan. 6) in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

The ankle bone fossils reveal that Dormaalocyon lived an arboreal life, scampering through the trees in what was then a humid, subtropical forest, the researchers report. It likely looked like something of a cross between a tiny panther and a squirrel, with a long tail and a catlike snout.

Reconstructing the carnivore family tree

The study confirms previous work suggesting that carnivores emerged during the Paleocene, before Dormaalocyon's time, said Gregg Gunnell, the director of the division of fossil primates at the Duke Lemur Center in North Carolina, who was not involved in the research.

"It really shows that there is a lot of diversity very early in the Eocene, and we have absolutely no idea where it came from," Gunnell told LiveScience.

Part of the challenge of uncovering carnivore history is that, on the whole, meat-eating mammals aren't that common, Gunnell said — there are many more herbivores and omnivores on the planet and in the fossil record. In addition, Solé said, fossils from Europe, which appears to be an important stop for, and potentially the origin of, carnivore evolution and spread, are rarer than fossils from North America.

The geographical origin of the carnivoraforms remains mysterious, however. One theory holds they originated in North America and spread to Europe; the relationships of the fossils in Dormaal seem to suggest something more complex, Solé said. It's possible that carnivoraforms began in Asia and made it to North America through Europe.

With the current fossil record, however, it's just not possible to say for sure. Solé and his colleagues will soon publish a paper on a new fossil site in France from the late Paleocene — and a new carnivorous mammal found there — that may hold answers.

"We need to find some Paleocene deposits that produce some kind of ancestors of these carnivoraforms," Gunnell said. "We're lacking a big chunk of information."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus