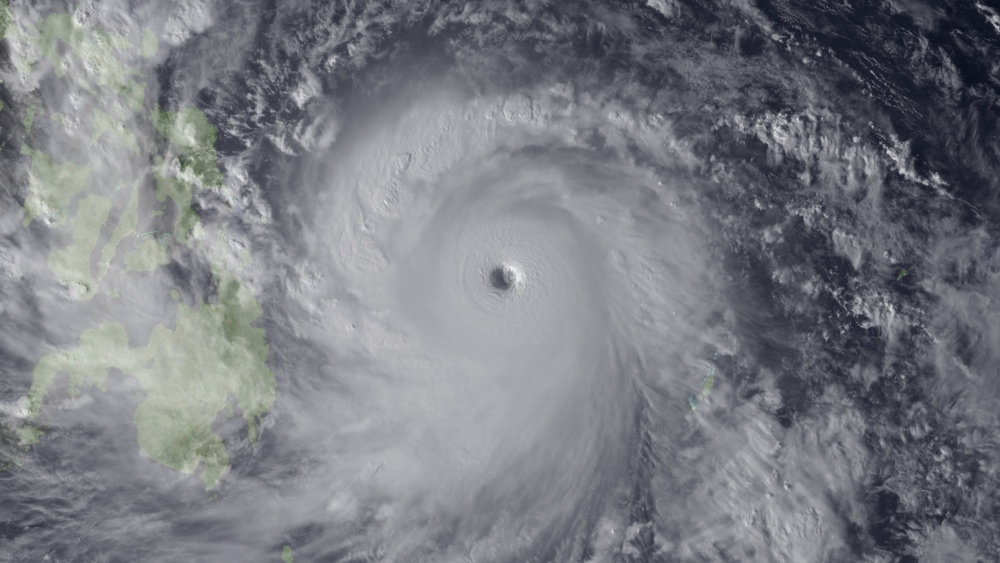

How Typhoon Haiyan Became Year's Most Intense Storm

A monstrous storm has arisen in the Western Pacific, the likes of which haven't been seen for several years, meteorologists say. The storm, Super Typhoon Haiyan, has become the year's most intense and is bearing down on the central Philippines, threatening to inflict massive damage and loss of life in the area.

The tropical cyclone (the blanket term for hurricanes and typhoons) packs winds up to 200 mph (320 km/h), according to estimates from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), with gusts up to 225 mph (360 km/h), said Brian McNoldy, a tropical weather expert at the University of Miami. This is the equivalent of a very strong Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, used to rank cyclones in the Atlantic Ocean.

"It's about as strong as tropical cyclones can get on Earth," McNoldy told LiveScience.

Ryan Maue, a meteorologist with Weatherbell Analytics, wrote on Twitter that Haiyan has the strongest winds seen since the 1979 Super Typhoon Tip, the largest and most intense tropical cyclone on record. Haiyan's winds make it the strongest storm in the satellite era. [8 Terrible Typhoons]

Haiyan got so strong because "it has everything working for it," McNoldy said. First, it formed in the open ocean, and thus no land mass prevented it from forming a symmetrical circular pattern, which helps a cyclone form and gather steam, he said.

Second, ocean temperatures are incredibly warm, topping out at 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius). Just as important, the warm water also extends deep into the ocean, meaning that upwelling caused by the winds will not churn up cold water, which dampens cyclone power, McNoldy said. Tropical cyclones are basically giant heat engines, powered by the transfer of heat from the ocean to the upper atmosphere.

Third, there is very little wind shear in the area at this time, McNoldy said. Wind shear, a difference in wind speed or direction with increasing altitude, tears developing hurricanes apart, and prevents them from strengthening. Wind shear caused by westerly winds is the main reason why the Atlantic hurricane season featured few strong storms, and got off to a late start, weather experts say.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Haiyan is the 11th typhoon to form in the Western Pacific in the last seven weeks, which has been an "exceptionally active period," according to the UK Met Office News Blog. It is also the year's fifth super typhoon.

This is somewhat unusual, because the peak of typhoon season usually occurs about one month earlier, McNoldy said. Wind shear in the area likely prevented that from happening, and now the area has become active again due to the weakening of upper-level winds and persistent warm surface waters, he added.

In the Western Pacific, a tropical storm becomes a typhoon when its wind speeds reach 74 mph (119 km/h). They become super typhoons when their winds reach 150 mph (241 km/h), making them equivalent to strong Category 4 or 5 hurricanes, according to NOAA.

Haiyan is likely to push a large storm surge inland — at least 10 feet (3 meters) — along the eastern coast of the islands of Luzon and Samar, according to the Washington Post's Capital Weather Gang blog.

The storm is expected to make landfall near where a deadly magnitude-7.1 earthquake struck the country less than one month ago, killing more than 200 people, according to news reports.

Email Douglas Main or follow him on Twitter or Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook or Google+. Article originally on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus