Worms Tell a Tale of How Nerves Develop

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

How nerve cells branch out and develop is a somewhat mysterious process, but a new study reveals how at least some of these nerves reach their target.

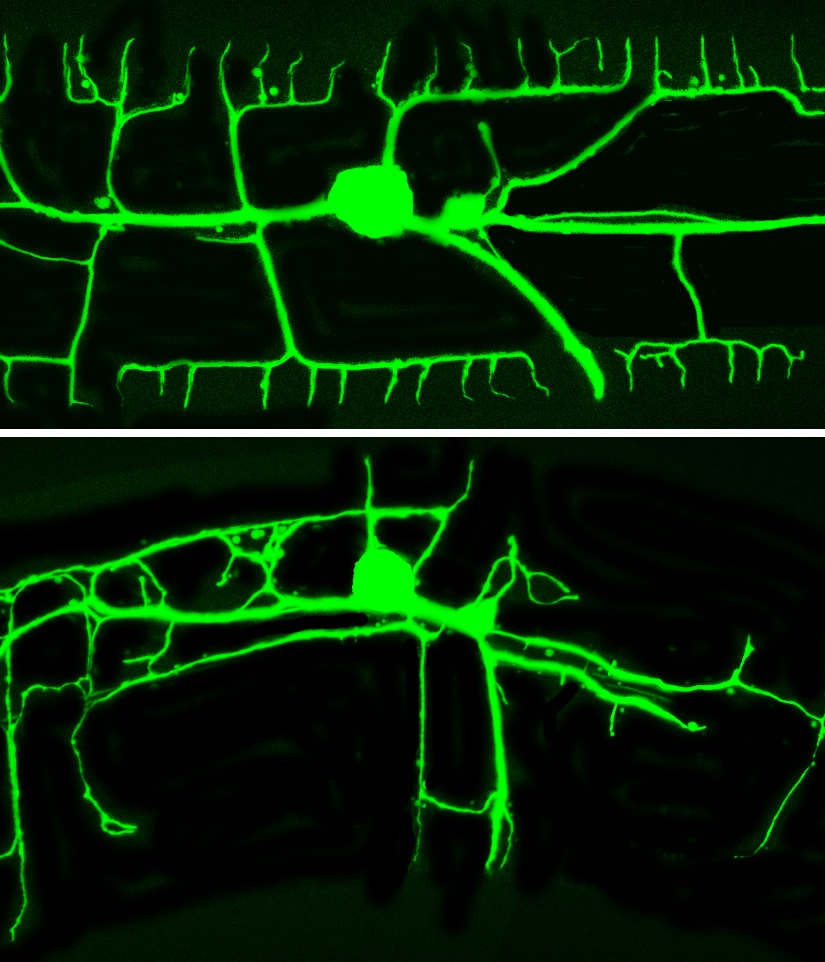

Nerve cells throughout the body form treelike structures known as dendrites that sense input from their environment and relay it to the nervous system. Now, researchers have found a protein in the skin of roundworms (Caenorhabditis elegans) that attracts growing dendrites, and the same protein may be present in humans.

Decades ago, scientists found a link between defects in dendrite development and neurological diseases such as Alzheimer's and schizophrenia. Understanding how these defects form in roundworms could offer insight into these disorders in humans. [Living With Alzheimer's in the US (Infographic)]

"I cannot imply we will understand Alzheimer's disease now, but it's not impossible that related mechanisms are also acting in humans," said study researcher Hannes Buelow, a geneticist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

To understand how dendrites form, Buelow and his team focused on roundworms, which are frequently used as models in genetics studies because the tiny animals are so easy to work with. The researchers performed a genetic screen to look for mutations that led to defective dendrites on pain-sensing cells, known to cover nearly the entire worm in a weblike structure.

The analysis revealed a gene for a protein manufactured in the worm's skin that controls proper dendrite branching. They called the protein menorin, because it leads to dendrites that resemble a menorah.

Using transgenic methods, the researchers inserted a normal copy of the menorin gene into the defective worms, and found it restored proper dendrite development on the pain-sensing cells, but only if the gene was inserted into skin cells.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings were exciting for two reasons, Buelow said. First, the gene turned out to exist in other animals, including humans. Until now, this gene hadn't been studied in any organism, Buelow said. And second, this was the first evidence that target signals from the skin were controlling dendrites. The only other example of this kind of signaling involves a class of proteins called neurotrophins, which are involved in neuron growth in the brain.

The findings are detailed today (Oct. 10) in the journal Cell.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus