Causes of Pakistan Earthquake & New Island Revealed

The powerful earthquake that hit Pakistan on Tuesday (Sept. 24) and killed more than 320 people struck along one of the most hazardous yet poorly studied tectonic plate boundaries in the world.

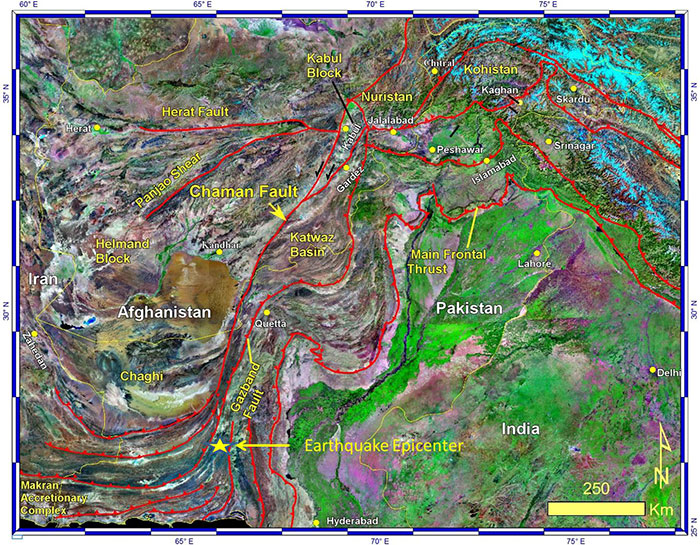

The magnitude-7.7 earthquake was likely centered on a southern strand of the Chaman Fault, said Shuhab Khan, a geoscientist at the University of Houston. In 1935, an earthquake on the northern Chaman Fault killed more than 30,000 people and destroyed the town of Quetta. It was one of the deadliest quakes ever in Southeast Asia.

Shaking from yesterday's earthquake in Pakistan demolished homes in the Awaran district near the epicenter, according to news reports. The death toll will likely rise as survivors and emergency workers search the debris.

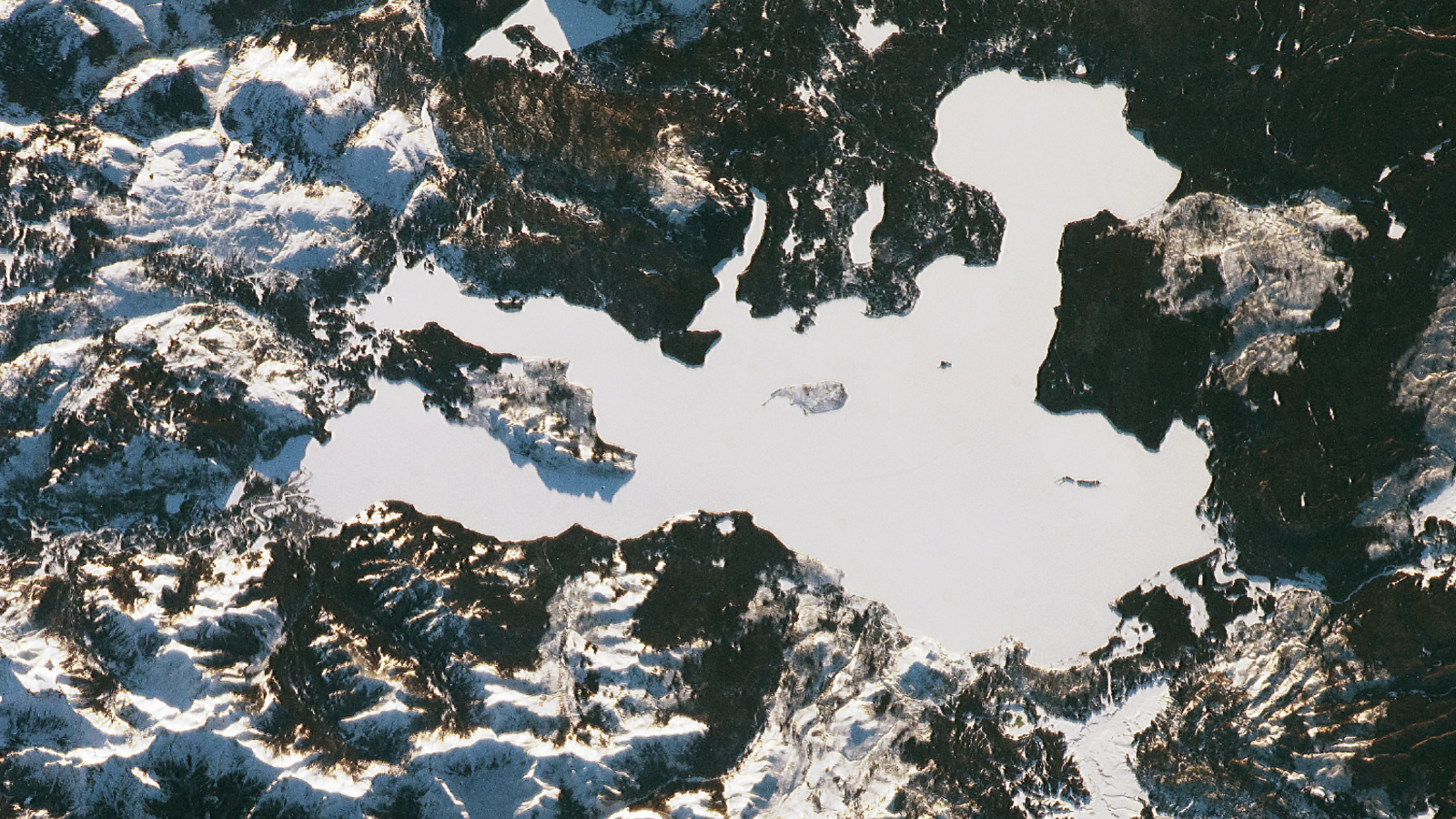

In the hours after the quake, a new island suddenly rose offshore in shallow seas near the town of Gwadar, about 230 miles (380 kilometers) southwest of the epicenter. Geologists with the Pakistan Navy have collected samples from the rocky pile, the Associated Press reported. From pictures and descriptions, many scientists think the mound is a mud volcano, which often erupt after strong earthquakes near the Arabian Sea. A second island has also been reported offshore of Ormara, about 170 miles (280 km) east of Gwadar, Geo News said.

"Other mud volcanoes have been triggered at this distance for similar size earthquakes," Michael Manga, a geophysicist and expert on mud volcanoes at the University of California, Berkeley, told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Little known risk

The unexplained island may have focused unusual global attention on the earthquake, which hit in a region that frequently experiences devastating temblors. [Video: Island Appears After Pakistan Earthquake]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But despite the hazards faced by millions living near the Chaman Fault, a combination of geography and politics means the seismic zone remains little studied. The Taliban killed 10 climbers, including an American, in northern Pakistan in June.

"Its location is in an area that is very difficult to do any traditional field work," Khan told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet. "I tried twice to submit proposals to [the National Science Foundation] and I got excellent reviews, but the review panel said I was risking my life to work in that area."

But the National Academy of Sciences felt differently. With their support, Khan and his colleagues in Pakistan and at the University of Cincinnati are now studying the fault's current and past movement. This will help the researchers forecast future earthquake risk.

"This fault has had very little work and no paleoseismology," Khan said. "It is really important."

Complex collision zone

Pakistan's deadly earthquakes owe their birth to the juncture of three colliding tectonic plates: Indian, Eurasian and Arabian. The Indian and Eurasian plates grind past each other along the Chaman Fault, triggering destructive temblors.

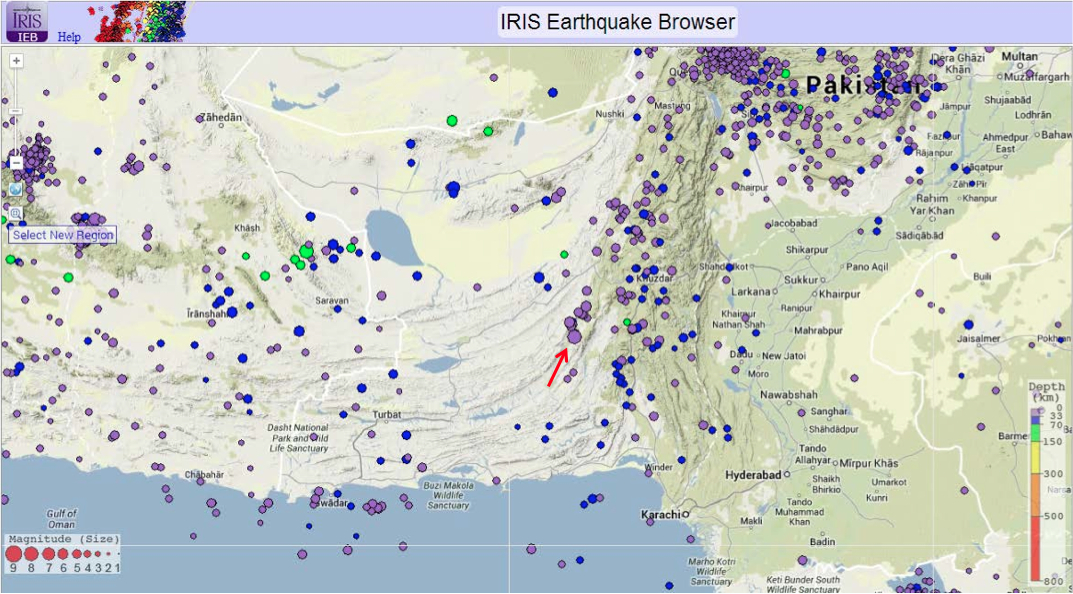

Earthquakes along the Chaman Fault are more frequent in the north than in the south, Khan said. Similar to California's San Andreas Fault or Turkey's East Anatolian Fault, in some spots, the massive plate boundary is not a single fracture. In southern Pakistan, the Chaman Fault splits into more than one strand, weaving a braid of many smaller faults. The differences between north and south influence the number of earthquakes. In the past 40 years, only one quake bigger than magnitude 6.0 has jiggled southern Pakistan within 125 miles (200 km) of yesterday's shaker, according to the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology in Seattle. [High & Dry: Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau]

Altogether, the strike-slip Chaman Fault spans more than 500 miles (860 kilometers), crossing through Afghanistan and Pakistan. Strike-slip faults move each side of the fracture mostly parallel to each other.

In the north, near the town of Chaman where India jabs a knuckle into Pakistan, the fault has zipped along at 33 millimeters (1.3 inches) every year for the past 38,000 years, according to a study Khan's team published Sept. 12 in the journal Tectonophysics.

"That is very fast," Khan said. "That tells me there were multiple major earthquakes in the last 38,000 years."

Many mud volcanoes

The ongoing tectonic crash in Pakistan also helps create the mud volcanoes that pop up after earthquakes there. "Whenever there is a major earthquake there are mud volcanoes," Khan said.

The spectacular mountains and roaring rivers of the Pamirs and the Himalayas deliver huge piles of wet silt and mud to the Arabian Sea. Jiggling these wet, gassy layers triggers an eruption of trapped water, Manga said. Think of liquefaction — when saturated soil loses its strength — but on a titanic scale.

The gray, dome-shaped mass offshore of Gwadar is 60 feet (18 meters) high, 100 feet (30 m) long and 250 feet (76 m) wide, a geologist with the Pakistan Navy told Geo News.

Stones on top of the pile suggest the muck roared out of the sea fast enough to carry solid rock.

"Given the size, it must have erupted pretty quickly," Manga said. Mud volcanoes in the northern Apennine Mountains in Italy have tossed rocks up to a meter (3 feet) in size, he said. Manga calculated the mud must have erupted at several meters per second (a few miles per hour) to throw the rocks.

There are about 1,000 mud volcanoes worldwide, and the ones that erupt at sea are ephemeral, soon disappearing under the waves. In 2001, a magnitude-7.7 earthquake in India birthed a short-lived mud volcano 300 miles (480 km) away. And at least five mud volcanoes surfaced in the Arabian Sea in 1945 after a massive magnitude-8.1 shock on the Makran subduction zone offshore of Pakistan, including one near Gwadar.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.