Mad Geniuses: 10 Odd Tales About Famous Scientists

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Odd Bunch

Scientists are a notoriously strange bunch.

After all, it helps to be a little bit different to pursue ideas that no one else believes in. Many scientists have had eccentric or prickly personalities, while others were polymaths who couldn't understand the limitations of other people's feeble brains. And quite a few have gone to extraordinary lengths in their quest for knowledge, with both terrifying and hilarious results.

From Tycho Brache's tame elk to Paul Erdős' amphetamine-fueled math benders, here are 10 of the strangest facts about the world's most famous scientists and mathematicians. [Top 10 Mad Scientists]

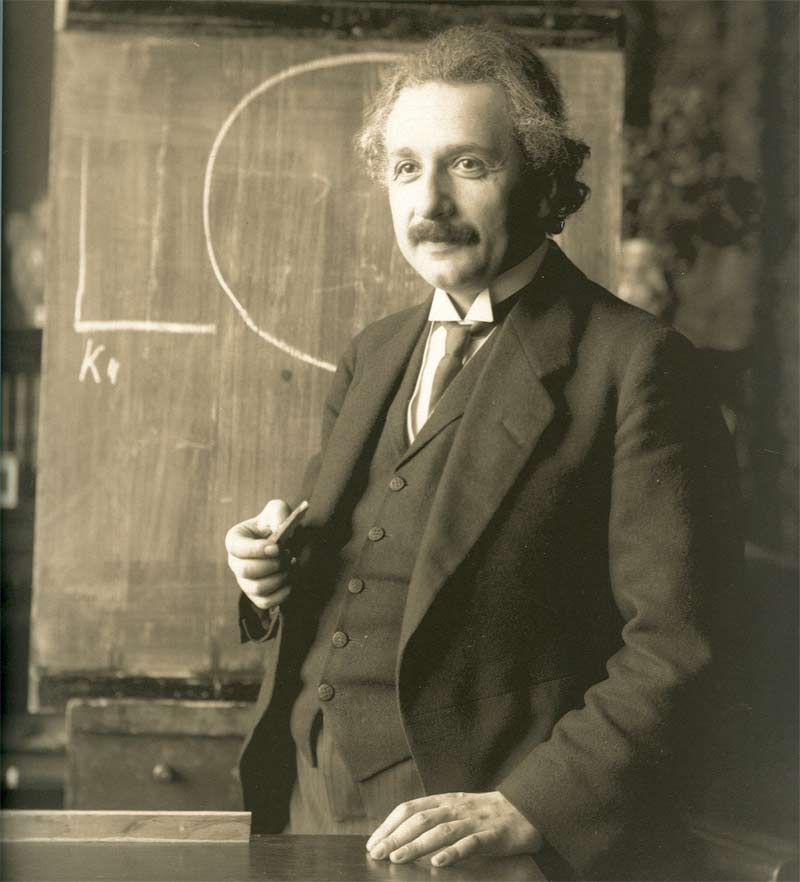

No Beans!

You can thank Greek mathematician Pythagoras for that geometry staple, the Pythagorean theorem. But some of his ideas haven't stood the test of time. For instance, Pythagoras espoused a philosophy of vegetarianism, but one of its tenets was a complete prohibition on touching or eating beans. Legend has it that beans were partly to blame for Pythagoras' death. After being chased from his house by attackers, he came upon a bean field, where he allegedly decided he would rather die than enter the field — and his attackers promptly slit his throat. (Historical records don't show a clear reason for the attacks.)

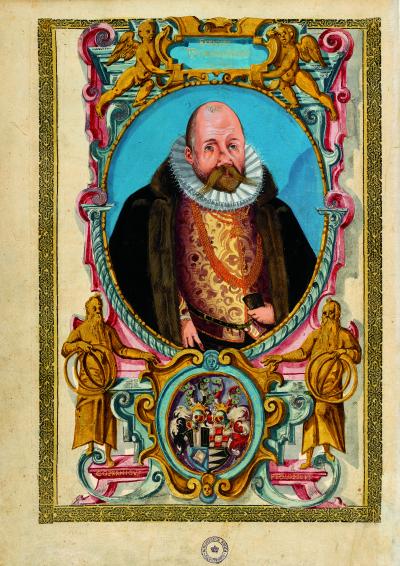

When you gotta go

The 16th-century Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe was a nobleman known for his eccentric life and death. He lost his nose in a duel in college and wore a prosthetic metal one ever after. And he loved to party: He had his very own island, and he invited friends over to his castle for wild escapades. He made sure guests saw an elk he had tamed and a dwarf named Jepp he kept as a "court jester" to permanently sit under the table, where Brahe occasionally fed him scraps of food. But his love of parties may have inadvertently been the death of him. At a banquet in Prague, Brahe insisted on staying at the table when he needed to pee, because leaving the table would be a breach of etiquette. That was a bad move, as Brahe developed a kidney infection and his bladder burst 11 days later in 1601.

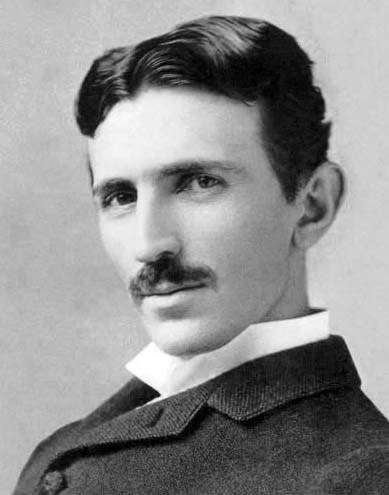

Unsung Hero

Nikola Tesla was one of science's unsung heroes. He arrived in America from Serbia in 1884 and quickly went to work for Thomas Edison, making key breakthroughs in radio, robotics and electricity, some of which Edison took credit for. (Tesla really invented the light bulb, not Edison). But Tesla wasn't just compulsive in his scientific quest. He probably had obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), refusing to touch anything even the slightest bit dirty, hair, pearl earrings or anything round. In addition, he became obsessed with the number 3, walking around a building three times before entering it. And at each meal, he would use exactly 18 napkins to polish the utensils until they sparkled. [Hoarding to Hypersex: 7 New Psychological Disorders]

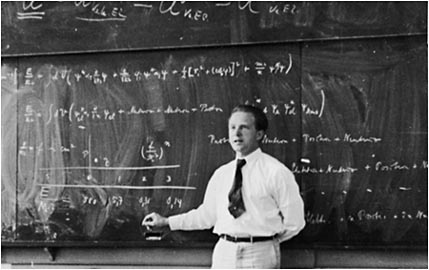

Absent-minded professor

Werner Heisenberg may be the quintessential brilliant theoretical physicist with his head in the clouds. In 1927, the German theoretical physicist developed the famous uncertainty equations involved in quantum mechanics, the rules that explain the behavior at small scales of tiny subatomic particles. Yet he nearly failed his doctoral exam because he knew almost nothing about experimental techniques. When a particularly skeptical professor on his doctoral-degree committee asked him how a battery worked, he had no idea. [The 9 Biggest Unsolved Mysteries in Physics]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

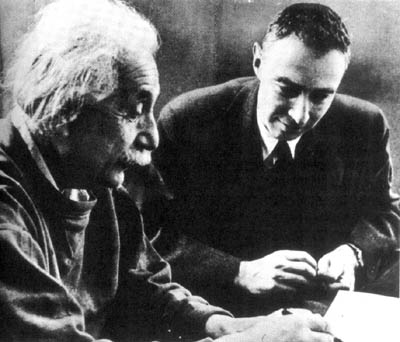

Prolific polymath

The physicist Robert Oppenheimer was a polymath, fluent in eight languages and interested in a wide range of interests, including poetry, linguistics and philosophy. As a result, Oppenheimer sometimes had trouble understanding other people's limitations. For instance, in 1931 he asked a University of California Berkeley colleague Leo Nedelsky to prepare a lecture for him, noting that it would be easy because everything was in a book that Oppenheimer gave him. Later on, the colleague came back befuddled because the book was entirely in Dutch. Oppenheimer's response? "But it's such easy Dutch!" [Images: The World's Most Beautiful Equations]

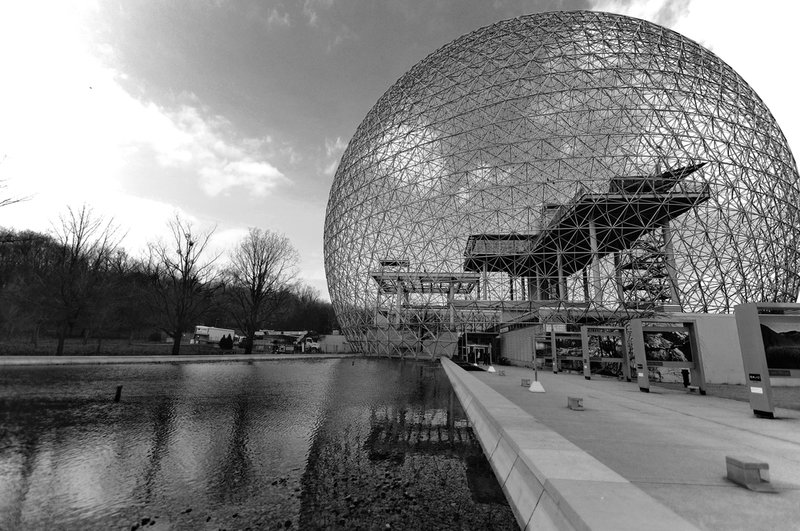

Documented to death

Architect and scientist Buckminster Fuller is most famous for creating the geodesic dome, sci-fi-esque visions of futuristic cities and a car called the Dymaxion in the 1930s. But Fuller was also a bit of an eccentric. He famously wore three watches to tell time in several time zones as he flew across the globe and spent years sleeping only two hours a night, which he dubbed Dymaxion sleep (he eventually gave it up because his colleagues couldn't keep up with not sleeping). But the genius also spent a lot of time chronicling his life. From 1915 to 1983, when he died, Fuller kept a detailed diary of his life that he updated religiously in 15-minute intervals. The resulting log, called the Dymaxion chronofiles, stacks 270 feet (82 meters) high and is housed at Stanford University.

Homeless mathematician

Paul Erdős was a Hungarian number theorist who was so devoted to his work that he never married, lived out of a suitcase, and often popped up on his colleagues' doorsteps without notice, saying "My brain is open," after which he would work on problems for a day or two before moving on. In his later years he guzzled coffee and took caffeine pills and amphetamines to stay awake, working on math 19 to 20 hours a day. His single-minded focus seemed to have paid off: The mathematician published about 1,500 important papers, and mathematicians now compute their "Erdős number," a six-degrees-of-separation number that describes how many people it would take to connect you to a Paul Erdős paper.

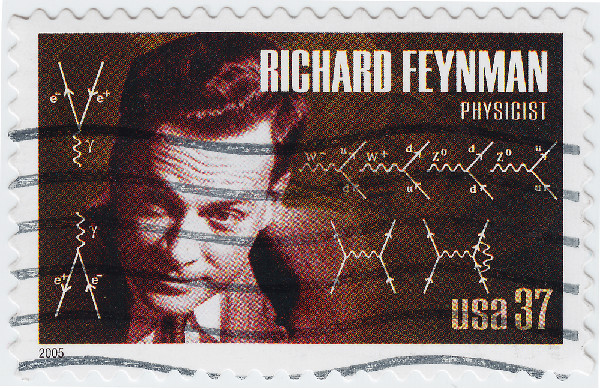

Physicist hijinks

Richard Feynman was one of the most prolific and famous physicists of the 20th century , famously involved in the Manhattan Project, the top-secret American effort to build an atomic bomb. But the physicist was also a bit of a practical joker and a mischief-maker. While bored at the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, N.M., Feynman reportedly spent his free time picking locks and cracking safes to show how easily the systems could be cracked. That wasn't the end of his adventures, however. On the way to developing his Nobel-prize winning theory of quantum electrodynamics, he would hang out with Las Vegas showgirls, become an expert in the Mayan language, learn Tuvan throat singing and explain how rubber o-rings led to the Challenger spacecraft's explosion in 1986.

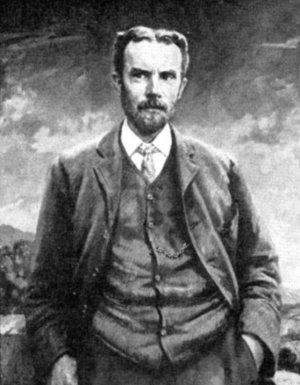

Heavy furniture

British mathematician and electrical engineer Oliver Heaviside developed complex math techniques to analyze electrical circuits and solve differential equations. But the self-taught genius was called a "first-rate oddity" by one of his friends. The engineer furnished his house with giant granite blocks, painted his nails bright pink, spent days drinking just milk and may have suffered from hypergraphia, a brain condition that causes an overwhelming urge to write.

Bone wars

During the great dinosaur rush of the late 1800s and early 1900s, two men used a series of increasingly shady tactics to surpass each other in the quest for dino fossils. Othniel Charles Marsh, a paleontologist at the Peabody Museum at Yale University, and Edward Drinker Cope, who worked at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, Penn., started out amicably enough, but soon grew to hate each other. On one fossil-hunting trip, Marsh bribed the keepers of a fossil pit to divert any finds his way. On another expedition, Marsh sent spies along on one of Cope's expeditions. Rumors swirled that they dynamited each other's bone beds to prevent one another's discoveries. They spent years publicly humiliating each other in scholarly articles and accusing each other of financial misdeeds and ineptitude in newspapers. Still, the two researchers made great contributions to the field of paleontology: Iconic dinosaurs such as Stegosaurus, Triceratops, Diplodocus andApatosaurus were all unearthed thanks to their efforts.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus