Warm and Buttery: Melt Speeds Greenland's Ice Flow

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

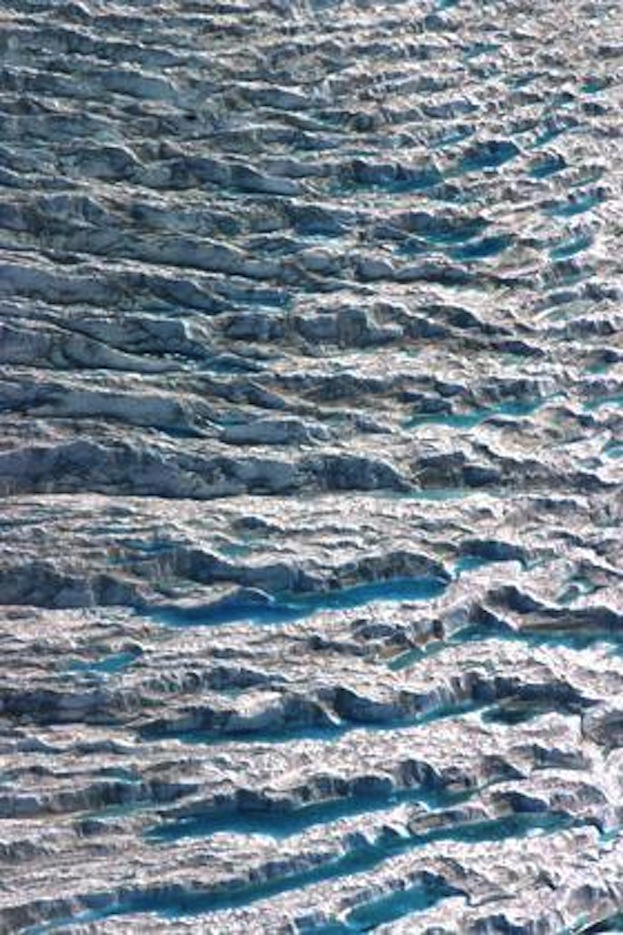

Greenland's massive ice sheet is accelerating its slide toward the ocean because bigger surface melts in recent years are softening the interior of the ice like a stick of butter, a new study finds.

For more than a decade, scientists have reported rapid melting and shrinking at many of Greenland's outlet glaciers, which snake into the ocean. Studies suggest warmer ocean water and rising atmospheric temperatures contribute to the melting ice. The new study finds the interior ice sheet also speeded up its flow to the sea in the past decade, but for a different reason. The ice sheet is changing from within.

"It's not just melt at the edge that's affecting how Greenland is changing," said Thomas Phillips, lead study author and a glaciologist at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at the University of Colorado Boulder. "This is a totally different mechanism. It comes from within the ice, and that's why we think this is such an important finding. This ice is changing its behavior as a whole, not just at the edges."

Like butter

Surface meltwater ponds and lakes form on top of Greenland's ice sheet and glaciers every summer. The water pressure can fracture the surface, creating a vertical drainpipe that carries the surface meltwater into the ice, even down to the rock at its base. The liquid lubricates the ice sheet, helping it slide more easily.

But the researchers also think the meltwater is softening the solid ice, making it deform like a stick of butter. The water transports heat into the chilly interior ice, according to computer modeling by the research team. The softer ice also flows more quickly, the modeling suggests. [Image Gallery: Greenland's Melting Glaciers]

The study focused on Sermeq Avannarleq Glacier in southwest Greenland. Located about 40 to 60 miles (65 to 95 kilometers) from the coast, the glacier is flowing about 1.5 times faster than it was 10 years ago. In 2000, the inland segment was flowing about 130 feet (40 meters) per year; in 2007-08, that speed was closer to 200 feet (60 m) per year.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Additional work by the team hints that other regions of Greenland's ice sheet are also accelerating because of surface melting, Phillips said. "There are indications that this is going on in large areas, and we're probably going to see more of this happening in the future," Phillips told LiveScience.

Glaciers slow, ice sheet speeds up?

The new findings also suggest Greenland's future melt may be more extensive than recent studies conclude. Some scientists think the rapid shrinking of its outlet glaciers may slow in coming decades. But even if the outlet glaciers slow down, the interior ice sheet could continue to speed up, spurred on by the extensive surface melts of recent years, Phillips said.

In 2012, nearly the entire surface veneer of Greenland's ice sheet melted, the biggest surface melt since record-keeping started 30 years ago.

"When we started studying this in 2005, we didn't expect to see all of Greenland melt within our lifetime, and seven years later it happened. It's changing very, very rapidly up there," Phillips said.

The findings were published May 6 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus