What Is El Niño?

El Niño is a climate cycle in the Pacific Ocean with a global impact on weather patterns.

The cycle begins when warm water in the western tropical Pacific Ocean shifts eastward along the equator toward the coast of South America. Normally, this warm water pools near Indonesia and the Philippines. During an El Niño, the Pacific's warmest surface waters sit offshore of northwestern South America.

Forecasters declare an official El Niño when they see both ocean temperatures and rainfall from storms veer to the east. Experts also look for prevailing trade winds to weaken and even reverse direction during the El Niño climate phenomenon. These changes set up a feedback loop between the atmosphere and the ocean that boosts El Niño conditions. The El Niño forecast for 2015 is expected to be one of the strongest on record, according to Mike Halpert, the deputy director of the Climate Prediction Center, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

"We don't want to see just the warming in the ocean. We want to see the atmosphere above the ocean respond to the changes," said Michelle L'Heureux, a climate scientist and lead for the El Niño forecasting team at the Climate Prediction Center.

The location of tropical storms shifts eastward during an El Niño because atmospheric moisture is fuel for thunderstorms, and the greatest amount of evaporation takes place above the ocean's warmest water.

There is also an opposite of an El Niño, called La Niña. This refers to times when waters of the tropical eastern Pacific are colder than normal and trade winds blow more strongly than usual.

Collectively, El Niño and La Niña are parts of an oscillation in the ocean-atmosphere system called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO cycle, which also has a neutral phase.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What causes an El Niño?

Scientists do not yet understand in detail what triggers an El Niño cycle. Not all El Niños are the same, nor do the atmosphere and ocean always follow the same patterns from one El Niño to another.

"There isn't one big cause, which is one of the reasons why we can't predict this thing perfectly," L'Heureux said. "There is some predictability in the common features that arise with El Nino, which is why we can make forecasts of it. But it won't be exactly the same every time."

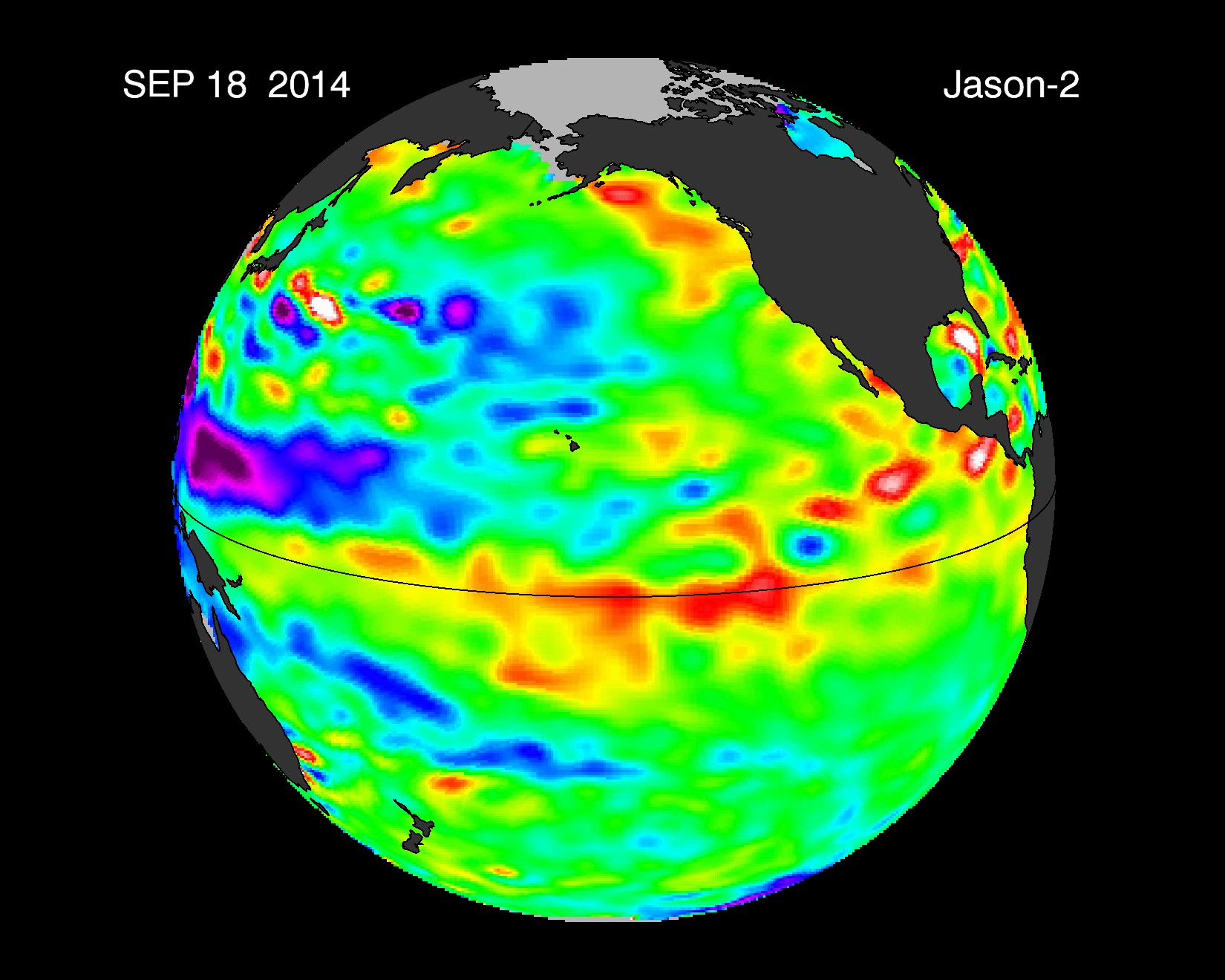

To forecast an El Niño, scientists monitor temperatures in the upper 656 feet (200 meters) of the ocean. They are watching for the telltale temperature shift from the western Pacific to the eastern Pacific. For example, in spring 2014, a very strong warm water swell called a "Kelvin wave" crossed the Pacific, leading some forecasters to predict a powerful El Niño for winter 2014. However, their forecast fizzled by fall because storms and trade winds never followed suit, and the feedbacks between atmosphere and ocean failed to develop.

"El Niños are never inevitable," L'Heureux said.

How often do El Niños occur?

El Niños occur every three to five years but may come as frequently as every two years or as rarely as every seven years. Typically, El Niños occur more frequently than La Niñas. Each event usually lasts nine to 12 months. They often begin to form in spring, reach peak strength between December and January, and then decay by May of the following year.

Their strength can vary considerably between cycles. One of the strongest in recent decades was the El Niño that developed the winter of 1997-98. "Everyone associates the word El Niño with that event, but that was a rare, once-in-a-century event," notes L'Heureux.

El Niño was originally named El Niño de Navidad by Peruvian fishermen in the 1600s. This name was used for the tendency of the phenomenon to arrive around Christmas. Climate records of El Niño go back millions of years, with evidence of the cycle found in ice cores, deep sea muds, coral, caves and tree rings.

What happens when El Niño is not present?

In normal, non-El Niño conditions, trade winds blow toward the west across the tropical Pacific, away from South America. These winds pile up warm surface water in the west Pacific, so that the sea surface is about 1 to 2 feet (0.3 m to 0.6 m) higher offshore Indonesia than across the Pacific, offshore Ecuador.

The sea-surface temperature is also about 14 degrees Fahrenheit (8 degrees Celsius) warmer in the west. Cooler ocean temperatures dominate offshore northwest South America, due to an upwelling of cold water from deeper levels. This nutrient-rich cold water supports diverse marine ecosystems and major fisheries.

When an El Niño kicks in

During an El Niño, the trade winds weaken in the central and western Pacific. Surface water temperatures off South America warm up, because there is less upwelling of the cold water from below to cool the surface. The clouds and rainstorms associated with warm ocean waters also shift toward the east. The warm waters release so much energy into the atmosphere that weather changes all over the planet.

Among the known effects of El Niño

The warmer waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean have important effects on the world's weather. The greatest impacts are generally not felt until winter or spring over the Northern Hemisphere, L'Heureux said. The 1982-83 El Niño is estimated to have caused more than $10 billion in weather-related damage worldwide. [How El Niño Causes Wild Weather All Over the Globe]

An El Niño creates stronger wind-shear and more-stable air over the Atlantic, which makes it harder for hurricanes to form. However, the warmer-than-average ocean temperatures boost eastern Pacific hurricanes, contributing to more-active tropical storm seasons.

Strong El Niños are also associated with above-average precipitation in the southern tier of the United States from California to the Atlantic coast. The cloudier weather typically causes below-average winter temperatures for those states, while temperatures tilt warmer-than-average in the northern tier of the United States. Rainfall is often below average in the Ohio and Tennessee valleys and the Pacific Northwest during an El Niño.

Record rainfall often strikes Peru, Chile and Ecuador during an El Niño year. Fish catches offshore South America are typically lower than normal because the marine life migrates north and south, following colder water.

El Niño also affects precipitation in other areas, including Indonesia and northeastern South America, which tend toward drier-than-normal conditions. Temperatures in Australia and Southeast Asia run hotter than average. El Niño-caused drought can be widespread, affecting southern Africa, India, Southeast Asia, Australia, the Pacific Islands and the Canadian prairies.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Additional resources

- NOAA: Impact of El Niño and La Niña on the Hurricane Season