Why Will It Take So Long to Fix the Large Hadron Collider?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

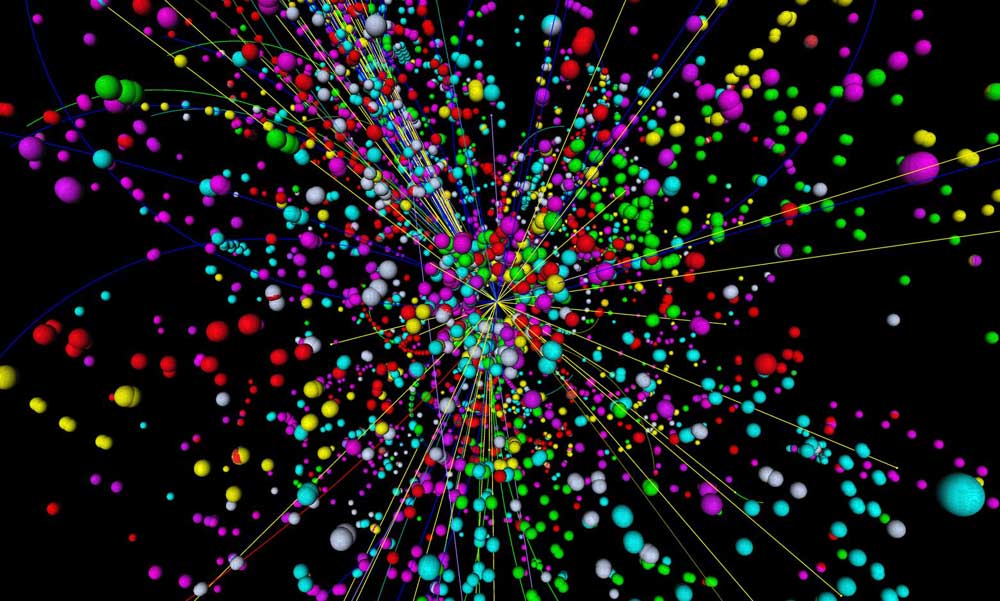

After all the hooplah over firing up the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the party turned out to be short-lived. On Sept. 20, the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Switzerland announced that a large helium leak, likely due to a faulty electrical connection, would require at least a two-month delay for repairs. A week later, scientists said they would not restart the machine until next spring.

This lengthy shutdown is necessary because scientists need to warm up the faulty area of the machine from its standard operating temperature of minus 456 degrees Fahrenheit — that’s a few degrees colder than outer space and only 3 degrees above absolute zero, the temperature where all molecules stop moving. It will take weeks to warm this errant area back up to room temperature so engineers can venture in and fix it. Then, assuming they can quickly detect and remedy the problem, scientists would need to lower the temperature again before turning the LHC back on.

The LHC requires such frigid temperatures because its electromagnets need outrageous amounts of current to harness the proton collisions. The wires used in our toasters and televisions are plagued by resistance that opposes the flow of electricity. But the special cables coiled throughout the LHC can function resistance-free — if they can be kept below a freezing -442 degrees. The elements used for these wires belong to a strange group called superconductors, which suddenly become perfect conductors of electricity at very low temperatures.

Without resistance, the machine runs far more efficiently because extra voltage isn’t needed to keep the electricity flowing. Yet even this frigid temperature cannot generate the type of energy CERN scientists desire. To harness 12,000 amps of electricity and speed up protons at 99.9999991 percent the speed of light, researchers lowered the temperature another 14 degrees to minus 456 degrees. This required some extra oomph from the refrigeration system.

"The LHC is more complex in cryogenics than any machine used before," says James Gillies, a CERN spokesman. The machine exhausts tons upon tons of liquid nitrogen and helium to keep the temperatures so low.

Unfortunately, while this system can make the LHC one of the coldest places on Earth, it also makes it difficult to warm the machine up again. "This type of problem would be trivial in other accelerators, but here it takes weeks to fix," says Gillies. In other words, controlling the levels of liquid nitrogen and helium to adjust the temperature is a lot more difficult than simply pressing the buttons on the thermostat in your house.

Based on these complications, and with the LHC already scheduled for winter maintenance, the powers that be decided to wait for the spring thaw. Until then, we’ll have to keep wondering what we’ll find when — or dare I say, if — the LHC begins recreating conditions from the dawn of our universe.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This answer is provided by Scienceline, a project of New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus