Trove of Neanderthal Bones Found in Greek Cave

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A trove of Neanderthal fossils including bones of children and adults, discovered in a cave in Greece hints the area may have been a key crossroad for ancient humans, researchers say.

The timing of the fossils suggests Neanderthals and humans may have at least had the opportunity to interact, or cross paths, there, the researchers added.

Neanderthals are the closest extinct relatives of modern humans, apparently even occasionally interbreeding with our ancestors. Neanderthals entered Europe before modern humans did, and may have lasted there until about 35,000 years ago, although recent findings have called this date into question.

To learn more about the history of ancient humans, scientists have recently focused on Greece.

"Greece lies directly on the most likely route of dispersals of early modern humans and earlier hominins into Europe from Africa via the Near East," paleoanthropologist Katerina Harvati at the University of Tübingen in Germany told LiveScience. "It also lies at the heart of one of the three Mediterranean peninsulae of Europe, which acted as refugia for plant and animal species, including human populations, during glacial times — that is, areas where species and populations were able to survive during the worst climatic deteriorations."

"Until recently, very little was known about deep prehistory in Greece, chiefly because the archaeological research focus in the country has been on classical and other more recent periods," Harvati added.

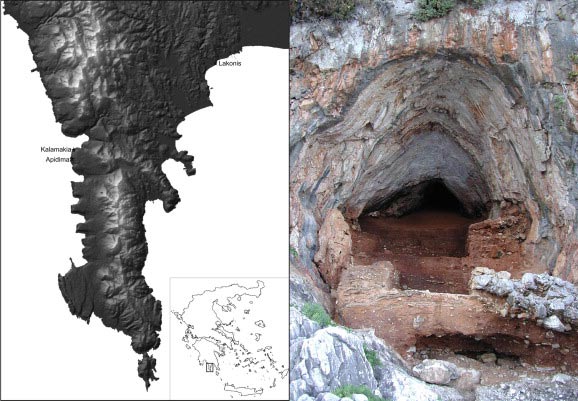

Harvati and colleagues from Greece and France analyzed remains from a site known as Kalamakia, a cave stretching about 65 feet (20 meters) deep into limestone cliffs on the western coast of the Mani Peninsula on the mainland of Greece. They excavated the cave over the course of 13 years. [Amazing Caves: Photos Reveal Earth's Innards]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The archaeological deposits of the cave date back to between about 39,000 and 100,000 years ago to the Middle Paleolithic period. During the height of the ice age, the area still possessed a mild climate and supported a wide range of wildlife, including deer, wild boar, rabbits, elephants, weasels, foxes, wolves, leopards, bears, falcons, toads, vipers and tortoises.

In the cave, the researchers found tools such as scrapers made of flint, quartz and seashells. The stone tools were all shaped, or knapped, in a way typical of Neanderthal artifacts.

Now, the scientists reveal they discovered 14 specimens of child and adult human remains in the cave, including teeth, a small fragment of skull, a vertebra, and leg and foot bones with bite and gnaw marks on them. The teeth strongly appear to be Neanderthal, and judging by marks on the teeth, the ancient people apparently had a diet of meat and diverse plants.

"Kalamakia, together with the single human tooth from the nearby cave site of Lakonis, are the first Neanderthal remains to be identified from Greece," Harvati said. The discoveries are "confirmation of a thriving and long-standing Neanderthal population in the region."

These findings suggest "the fossil record from Greece potentially holds answers about the earliest dispersal of modern humans and earlier hominins into Europe, about possible late survival of Neanderthals and about one of the first instances where the two might have had the opportunity to interact," Harvati said.

In the future, Harvati and her colleagues will conduct new fieldwork in other areas in Greece to address mysteries such as potential coexistence and interactions between Neanderthals and modern humans, the spread of modern and extinct humans into Europe and possible seafaring capabilities of ancient humans.

"We look forward to exciting discoveries in the coming years," Harvati said.

The scientists detailed their findings online March 13 in the Journal of Human Evolution.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus