What If Friday's Flyby Asteroid Hit Earth?

On Friday (Feb. 15), an asteroid half the length of a football field will buzz close by Earth. It won't hit the planet, but if it did, the collision would create an impact large enough to level 80 million trees — or the entire city of Washington, D.C., and its suburbs.

Scientists know this because an impact by an object the size of Friday's flyby asteroid has happened in human memory. In 1908, a 220-million-pound (100-million-kilogram) hunk of meteoroid or comet fragment hurtled into the atmosphere over Tunguska, Siberia, setting the sky ablaze and releasing the same amount of energy as 185 Hiroshima bombs.

Fortunately, the impact occurred over remote, forested land, taking the lives of hundreds of reindeer but no humans. At about 130 feet (40 meters) in diameter, the Tunguska space rock is similar in size to 2012 DA14, the asteroid en route for a Friday flyby, which is estimated to be about 150 feet (45 m). For comparison, that's about the size of the White House, said Mark Boslough, a physicist at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico who has used computer modeling to recreate the Tunguska impact.

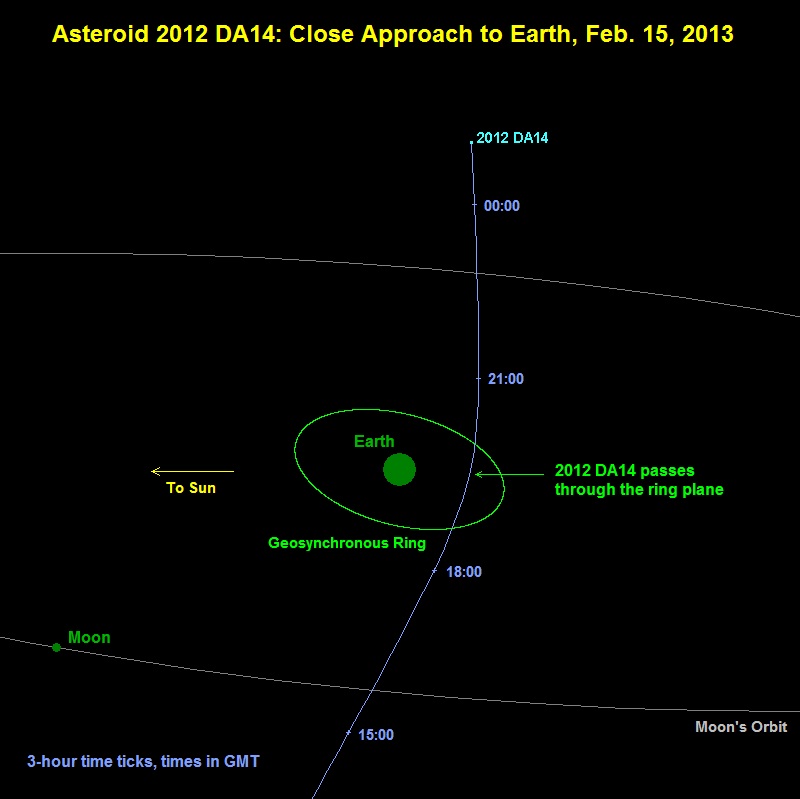

Asteroid 2012 DA14 will approach as close as 17,200 miles (27,700 kilometers) from Earth at approximately 2:24 p.m. Eastern Standard Time on Friday, the closest-ever predicted flyby for an object this large. The approach isn't close enough to threaten Earth, though it will pass within the zone where satellites are orbiting. Siberia in 1908 wasn't so lucky.

Fire in the sky

A little after 7 a.m. local time on June 30, 1908, a man sitting in a chair at the Vanavara trading post in Siberia was violently thrown from his seat. The sky "split in two," the man later told a visiting scientist, and was "covered with fire." [Top 10 Greatest Explosions Ever]

Although he was 40 miles (64 km) from the scene of the impact, the man felt so much heat that he thought his shirt was on fire, according to NASA. Other eyewitnesses reported explosive sounds like artillery fire.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Tunguska meteoroid likely entered the atmosphere at speeds of 33,500 miles per hour (539,130 km/h), NASA reports. There is no impact crater, because the pressure and heat caused by this screaming entry caused the space rock to explode. The blast leveled an area of about 800 square miles (1,287 square km).

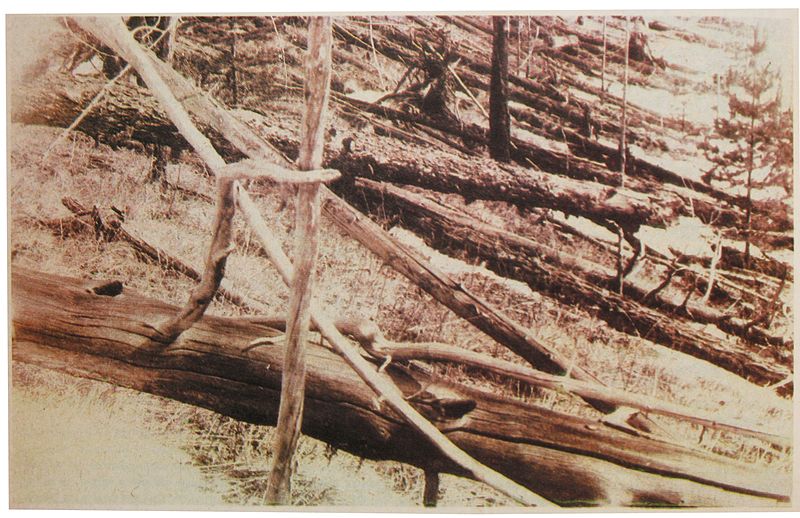

Scientists visiting the site could tell exactly where the Tunguska meteoroid broke up, because the blast flattened trees in a radial pattern, like tire spokes emanating out from ground zero.

Piecing together Tunguska

It wasn't until 1927 that a research expedition reached the remote site of the blast. Led by Leonid Kulik, the curator for the meteorite collection at the St. Petersburg Museum, the scientists found that at the center of the impact zone, trees remained standing — but had been stripped of all branches and bark, a sign of an extremely fast shock wave.

The damage was so extensive that scientists originally thought that the Tunguska object was much larger than now believed, Boslough told LiveScience. Boslough's best estimate is 130 feet (40 m) in diameter, possibly as small as 98 feet (30 m) or as large as 164 feet (50 m).

"As we understood impacts and air bursts better and better, the size kept shrinking," he said.

That's because asteroid impacts were originally thought of as similar to nuclear bomb explosions. But nuclear bomb blasts explode outward in all directions, while space objects hurtling toward Earth carry their energy in a single direction.

"There's an energy concentration directly below the airburst, below the asteroid explosion, that doesn't exist for a nuclear explosion," Boslough said.

Because there were only a few eyewitnesses to Tunguska and no scientific expedition to the area until 19 years after the fact, researchers have had to apply the lessons of later planetary impacts to unravel the mysteries of the 1908 event. The collision of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 with Jupiter in 1994 helped elucidate Tunguska, for example, Boslough said.

Asteroid 2012 DA14, the space rock that will pass by Earth Friday, is in no danger of hitting the planet. But if it did, the damage would be extensive, Boslough said, with the White House-sized asteroid capable of snuffing out the entire Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. [See Photos of Asteroid 2012 DA14]

Such impacts are estimated to occur on Earth every 1,000 to 2,000 years, Boslough said. But because the comets break up in the air and leave no impact crater, their tracks are hard to see. Forest has again sprung up over the Tunguska impact site, said Boslough, who has visited the area.

"If I didn't know that something had happened because of historical records, I would never suspect that anything had happened there," he said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus