Distant Human Ancestor Had Shark Head

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Peer far enough back in the human family lineage, and you'll find a fishy ancestor that looked surprisingly like a shark.

In fact, this now-extinct fish was among the first to split from sharks, whose bones are made of cartilage, to evolve into a line of tough-boned species that includes everything from bony fish to human beings. A new analysis finds that this controversial class of animals was more shark-like than expected.

"The common ancestors of all jawed vertebrates today organized their heads in a way that resembled sharks," study researcher John Finarelli, a vertebrate biologist at University College, Dublin, said in a statement. "Given what we now know about the interrelatedness of early fishes, these results tell us that while sharks retained these features, bony fishes moved away from such conditions."

Finarelli and his colleagues examined a fish called Acanthodes bronni, part of the acanthodian group of fish, which included the earliest vertebrate animals with jaws. A. bronni lived about 290 million years ago, during the Paleozoic period. The shark family and the bony fish families split about 460 million years ago. [Top 10 Missing Links]

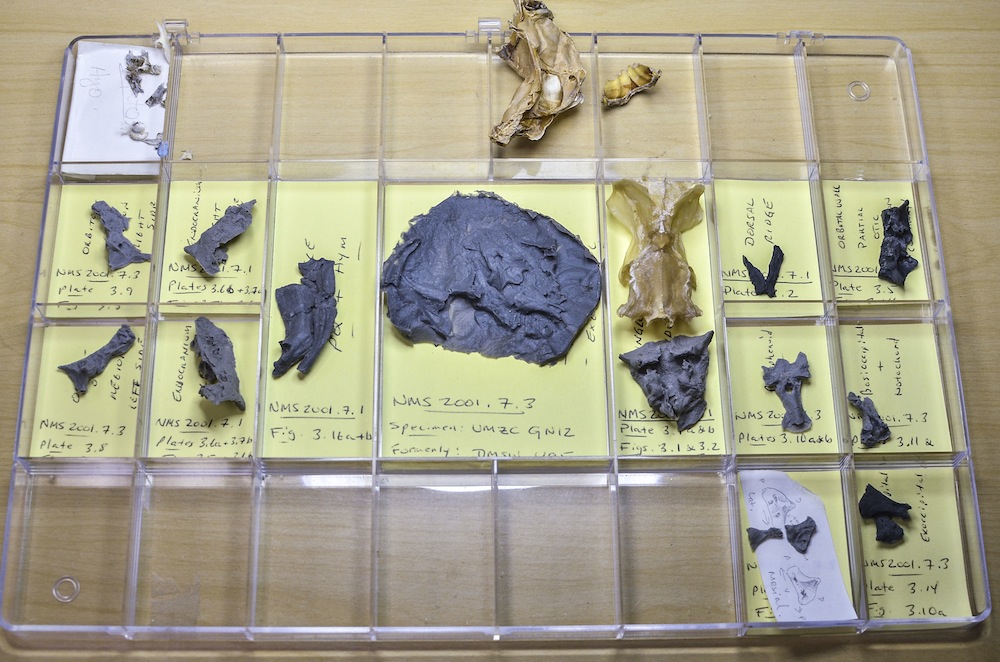

A. bronni left few traces besides its fossil scales and fin spines. But a few fossilized, fragmented skulls survived millions of years in the ground and now reside in museum collections. The researchers made silicone rubber casts of these fossils in order to reconstruct the anatomy of the fish's heads.

This closer-than-ever look revealed ridges and grooves never before examined. The researchers took 138 characteristics of the skulls and compared them with both the skulls of the chondrichthyes, the group made up of sharks and rays, and the osteichthyes, or bony fish such as today's sardines and mackerel. They found that on the whole, acanthodian heads fell in with the sharks.

"For the first time, we could look inside the head of Acanthodes, and describe it within this whole new context," study researcher Michael Coates, a University of Chicago biologist, said in a statement. "The more we looked at it, the more similarities we found with sharks."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study also revised the relationships between early gnathostomes, or vertebrates with jaws (whose members range from fish and sharks to birds, reptiles and humans), and the most primitive members of that group, armored fish called placoderms. The researchers found distinctive anatomical differences between placoderms and other gnathostomes.

All of the updated relationships will allow researchers to look more closely at how fish made the transition from jawless to jawed, Coates said.

"It helps to answer the basic question of what's primitive about a shark," he said. "And, at last, we're getting a better handle on primitive conditions for jawed vertebrates as a whole."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus