Caught in the Act: Ancient Armored Fish Downs Flying Reptile

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

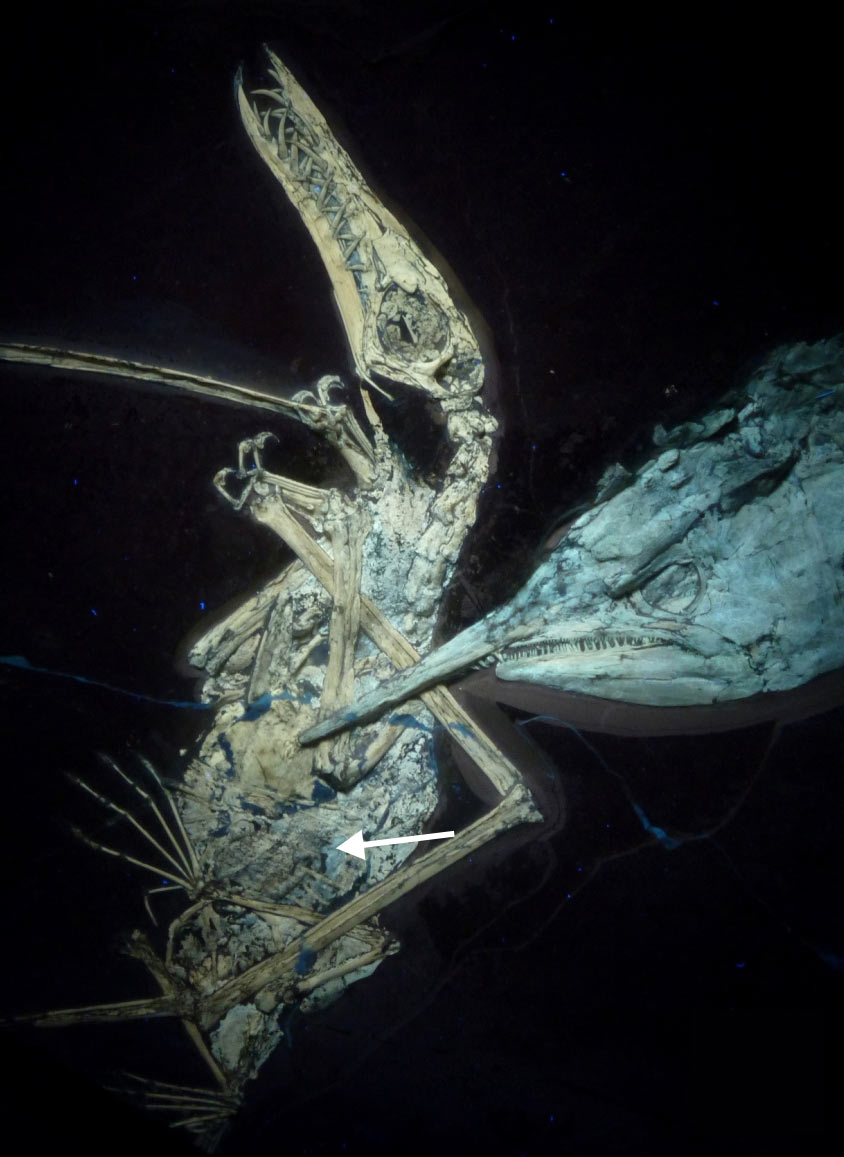

An ancient armored fish was fossilized in the act of attacking and drowning a pterosaur in a toxic Jurassic lake, revealing that the winged reptiles were victims of a wide variety of carnivores, scientists find.

Pterosaurs dominated the skies during the Age of Dinosaurs. Still, flight did not always ensure them safety — researchers have recently discovered that Velociraptor dined on the flying reptiles.

Now scientists have uncovered five examples of the long-tailed pterosaur Rhamphorhychus apparently within the jaws of the ancient armored predatory fish Aspidorhynchus. The fossils in question, unearthed in Bavaria in southern Germany, are about 120 million years old.

All of the pterosaur victims discovered, which had wingspans of about 27 inches (70 cm), were positioned such that their wings were near the mouths of their 25-inch-long (65 cm) fish predators. That suggests that the predator might have grabbed hold of their wing membranes. In one specimen, a pterosaur wing bone is actually caught within the jaws of the fish. In another of the fossils, the pterosaur has a tiny fish in its throat, apparently swallowing it headfirst. This suggests the flying reptile was alive when it was seized, and not dead and perhaps scavenged by the armored fish. [Album: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

The researchers speculate the Aspidorhynchus fish attacked the pterosaur while it was flying just above the water surface right after plucking a fish from the sea, grabbed the pterosaur's left wing and pulled the animal under water.

Nowadays birds and bats are occasionally eaten by sharks and other large fish. Still, the researchers do not think that pterosaurs were regularly part of the diet for Aspidorhynchus. In fact, these attacks were probably lethal mistakes.

"These animals normally have nothing to do with each other," said researcher Eberhard Frey, a paleozoologist at the State Natural History Museum in Karlsruhe, Germany. "Apparently these encounters were fatal for both of them."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fish could neither swallow the pterosaurs nor work their jaws free, since the fibrous tissue of a pterosaur's tough, leathery wings would have become entangled with the fish's densely packed teeth. After fighting the pterosaurs for a while, the fish would have likely sunk into the hostile, oxygen-poor water it lived in, where it would have suffocated.

"Fish sometimes don't take care with what they eat, because their brains are not very smart," Frey told LiveScience. "Occasionally you find fish that died because they ate another fish that was too big to get swallowed, and the same things happened here with these pterosaurs."

Frey and his colleague, Helmut Tischlinger, detailed their findings online March 7 in the journal PLoS ONE.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus