Dinosaur Guts Reveal Velociraptor's Last Meal

A lightweight Velociraptor dinosaur may have chowed down on the carcass of a much larger flying reptile not long before meeting his own demise some 75 million years ago.

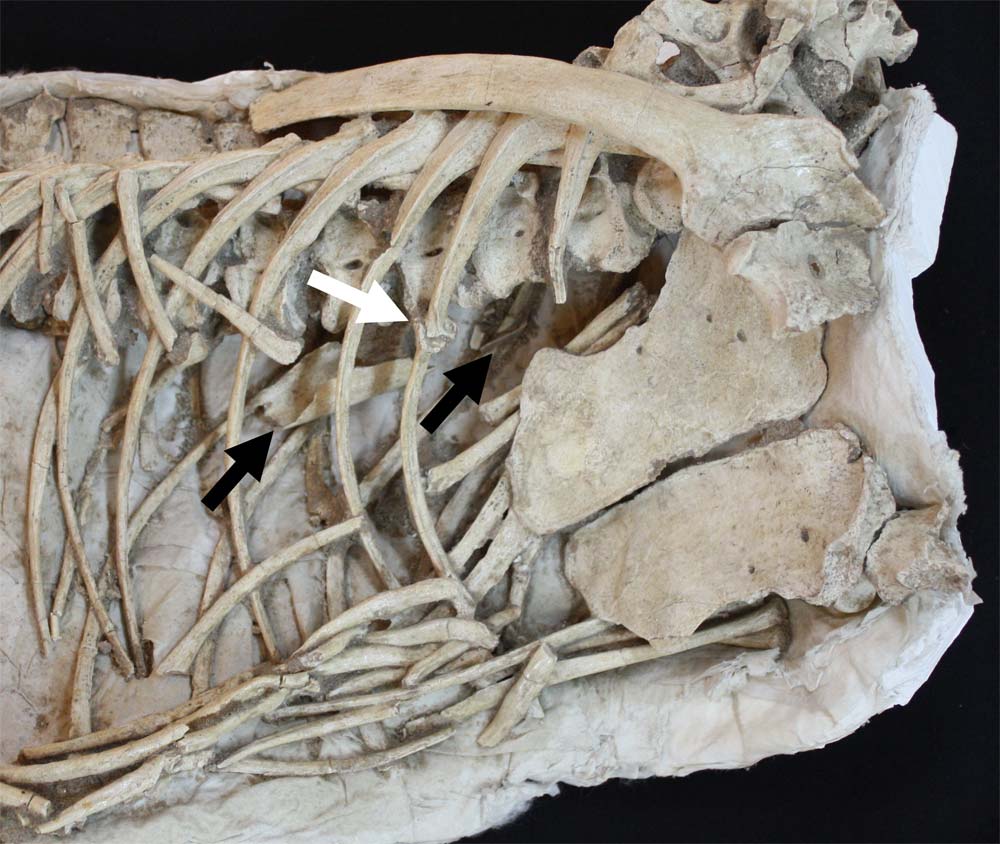

The evidence comes from a pterosaur bone discovered in the gut of the skeletal remains of what was likely a Velociraptor mongoliensis that lived in what is now the Gobi Desert in Mongolia. The fossil, the first pterosaur bone to be found inside dinosaur guts, was discovered in 1994 but not fully analyzed and detailed in a scientific publication until now.

Velociraptor was known to have fearsome sickle-shaped talons on the second toe of each foot; it kept these talons off the ground like foldable switchblades. Past research has shown these theropod dinosaurs used their talons to slash live prey and hook them to keep them from escaping.

The new study, which says the pterosaur may have been dead before the predator found it, adds to research suggesting the fierce carnivores wouldn't turn their back on a free meal, either. A study published in 2010 reported the discovery of a Velociraptor frozen in time, scavenging the corpse of a larger dinosaur.

"It would be difficult and probably even dangerous for the small theropod dinosaur to target a pterosaur with a wingspan of 2 meters [6.5 feet] or more unless the pterosaur was already ill or injured. So the pterosaur bone we've identified in the gut of the Velociraptor was most likely scavenged from a carcass rather than the result of a predatory kill," said study researcher David Hone, who was at the University College Dublin's School of Biology and Environmental Sciences in Ireland during the study of the remains.

The pterosaur's bone, measuring nearly 3 inches (75 millimeters) in length, was lodged in the upper part of the Velociraptor's ribcage where the stomach would have been. "The surface of the bone is smooth and in good condition, with no unusual traces of marks or deformation that could be attributed to digestive acids. So it's likely that the Velociraptor itself died not long after ingesting the bone," Hone said in a statement.

A broken rib with signs of regrowth also suggested the dinosaur was injured or recovering from an injury at the time of death, the researchers note online March 3 in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, and Palaeoecology.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

With an ability similar to modern crocodiles, these small non-avian dinosaurs could eat relatively large bones, the researchers said.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus