'Armored' Microbes Survived Harsh Post-Snowball Earth

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Tiny undersea organisms not only survived some of Earth's harshest weather, when the planet was covered in a sheet of ice some 700 million years ago, new microfossil evidence suggests they developed protective armor and thrived after "Snowball Earth."

Scientists hypothesize that Earth underwent two such global glaciations between 710 million and 635 million years ago. [The World's Weirdest Weather]

"What we found in Namibia and Mongolia was the first occurrence of microfossils in rocks deposited immediately after the first Snowball Earth event," study researcher Sara Pruss of Smith College told LiveScience. "Life not only survived this dramatic climate change but flourished in its immediate aftermath."

The fossils were collected from cap-carbonate rocks — the very first layers of sediment deposited after the first Snowball Earth — in southern Africa and eastern Asia.

"Our findings provide insight into microbial ecosystems that existed between the two global glaciations," Pruss said by email. "Because our organisms are found at a later time (the critical interval between the two glaciations), they are helping to fill in long-standing gaps in the fossil record."

Freeing the fossils

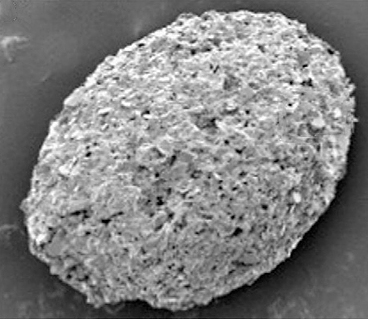

After freeing the trapped fossils from the rocks, study researcher Tonja Bosak of MIT and colleagues looked at them under a high-powered electron microscope. They saw what appeared to be hollow shells that may have held single-cell creatures.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The tiny, amoeba-like organisms probably built their armor from material gleaned from the surrounding environment. The shells looked like tiny black ovals with a single notch. The creatures may have grabbed things from their environment with their foot-like projections through the notch.

They would have been similar to a group of organisms called testate amoebae, which are still abundant in many land environments. However, the amoebae living during the post-Snowball Earth thrived in the oceans and probably made their way onto land sometime later in their evolution, Pruss said.

Building a shell

The shells were made of an amalgamation of minerals freely available in the creatures' environment, including silica, aluminum and potassium — the oldest example of "agglutination," or building a shell from minerals available around them. There were differences between shells from different sites, though; those from Namibia were rounder, while the ones from Mongolia were more tube-shaped.

The shells likely provided protection from the pressures of the deep ocean environment, and from other, possibly predacious organisms, though it's hard to tell what their environment was like, Pruss said.

Other shelled organisms had lived before the Snowball Earth event, though they seemed to have built their own, plate-like shells. They don't have any known counterparts today.

The study will be published in a forthcoming issue of the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus