How Mice Got their Sandy Coats: Beach Life

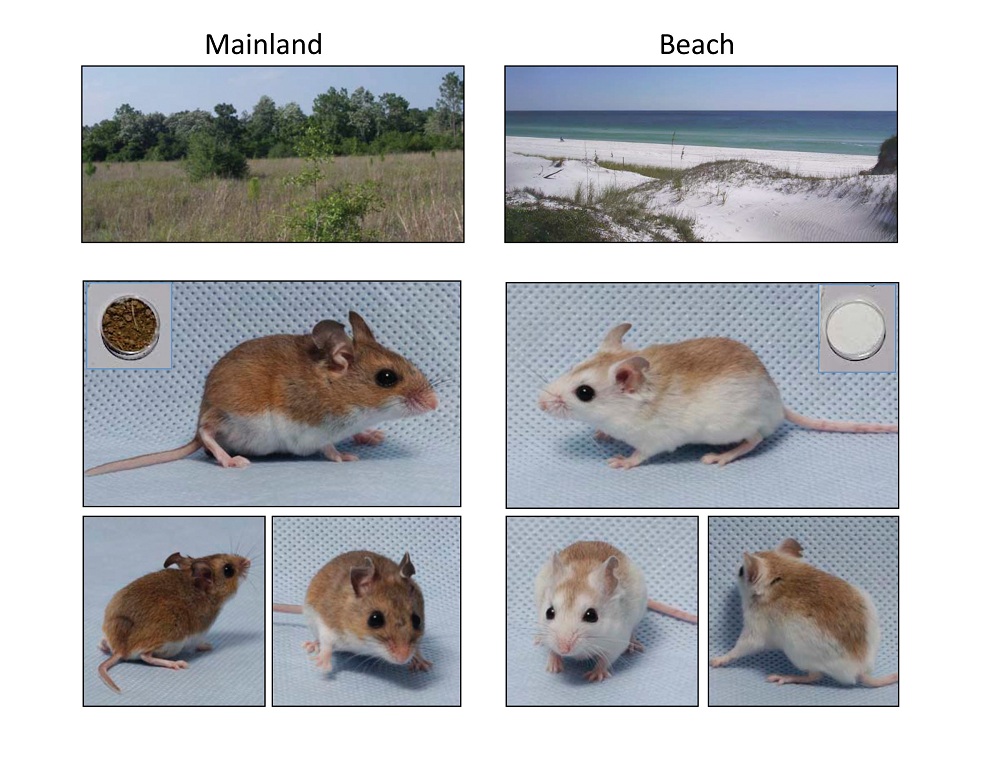

Over the past few thousand years, Florida's deer mice evolved lighter fur and different camouflaging to survive on beaches, a new study suggests.

The lighter tan color is controlled by one protein, called agouti, the researchers said, adding that the same protein could be the culprit for a leopard's spots and the coat patterns of other big cats.

"We were interested in understanding how color patterns are formed and how they change between species," lead study researcher Hopi Hoekstra of Harvard University said. "These can be really important for survival and reproduction for organisms in the wild."

The altered coloring in the beach mice evolved over time from the older, darker forest mice. The changes were caused by changes to the agouti protein, found in all vertebrates, which controls pigment-creating cells called melanocytes. The research showed that without agouti, these mice would be jet black.

Evolution in action

Various genes involved in color and patterns in animal coats have been identified in the lab, but this is the first time the mechanism has been seen in the wild.

"One of the most interesting questions about evolution is: 'How does it work in the real world?'" said Greg Barsh at Stanford University, who was not involved in the study. "That’s a major question in genetics and biology right now. Much of our understanding of the molecular basis of development is based on laboratory model organisms."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hoekstra found that higher levels of agouti protein, particularly in the white belly area of a developing mouse in the womb, led to the lighter coat color. The boundary area between the white belly and the darker back of the mouse also moved upward, shrinking the darker patch.

"If you change the expression of this gene in the embryo you get a totally new pattern," Hoekstra told LiveScience. "They've evolved a novel color pattern to blend in with the light sandy habitat."

Muddled melanocytes

Agouti changes the mouse's coloring by stopping the color-creating cells, called melanocytes, from maturing. Immature melanocytes don't make it into the hair follicles and can't make the pigments that color the mouse's coat, the team found. They also saw that by changing how much of the agouti is made and where it's made they could artificially change the coloring pattern.

Changing the expression of this protein doesn’t change anything other than the pigmentation, Hoekstra said. "It's pretty specific to the pigmentation pathway, if you change it you don't mess many other things up," she said. "It’s a good thing to tweak if you just want to change pigmentation."

The researchers are currently working on understanding more complex coloring patterns like the stripes on chipmunks and zebra mice.

"I think it’s a beautiful piece of work," Barsh told LiveScience. "One of the challenges that is often encountered in this type of work is taking a set of tools that was originally developed in lab animals and adapting them to a wild population."

The study will be published in tomorrow’s (Feb. 25) issue of the journal Science.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover .

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.